- Since early January 2023, China Labour Bulletin has recorded 108 factory workers’ protests, over twice the amount recorded in all of 2022;

- Reduced orders from international buyers and poor economic conditions have led factories to lay off workers, relocate to reduce costs, or shut down altogether;

- CLB’s study of these incidents reveals that the intent of China’s labour laws are not being followed, and international brands should take note of their responsibility to ensure suppliers comply with domestic laws.

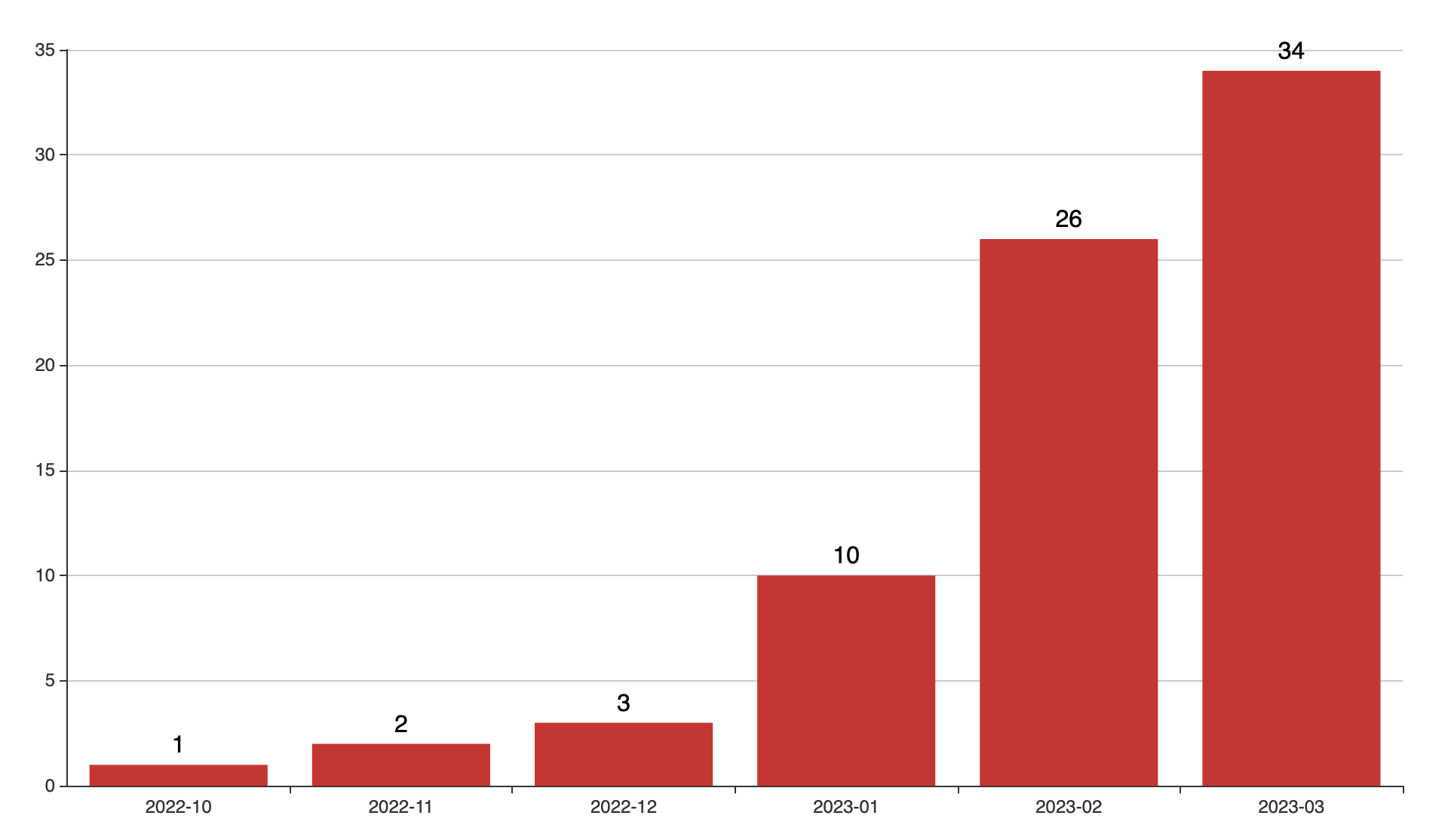

Strikes and protests in China’s manufacturing sector have surged since early 2023, as many factories in China face economic difficulties. In the first quarter of 2023, CLB’s Strike Map recorded a tenfold increase in incidents in the manufacturing sector, compared to the last quarter of 2022.

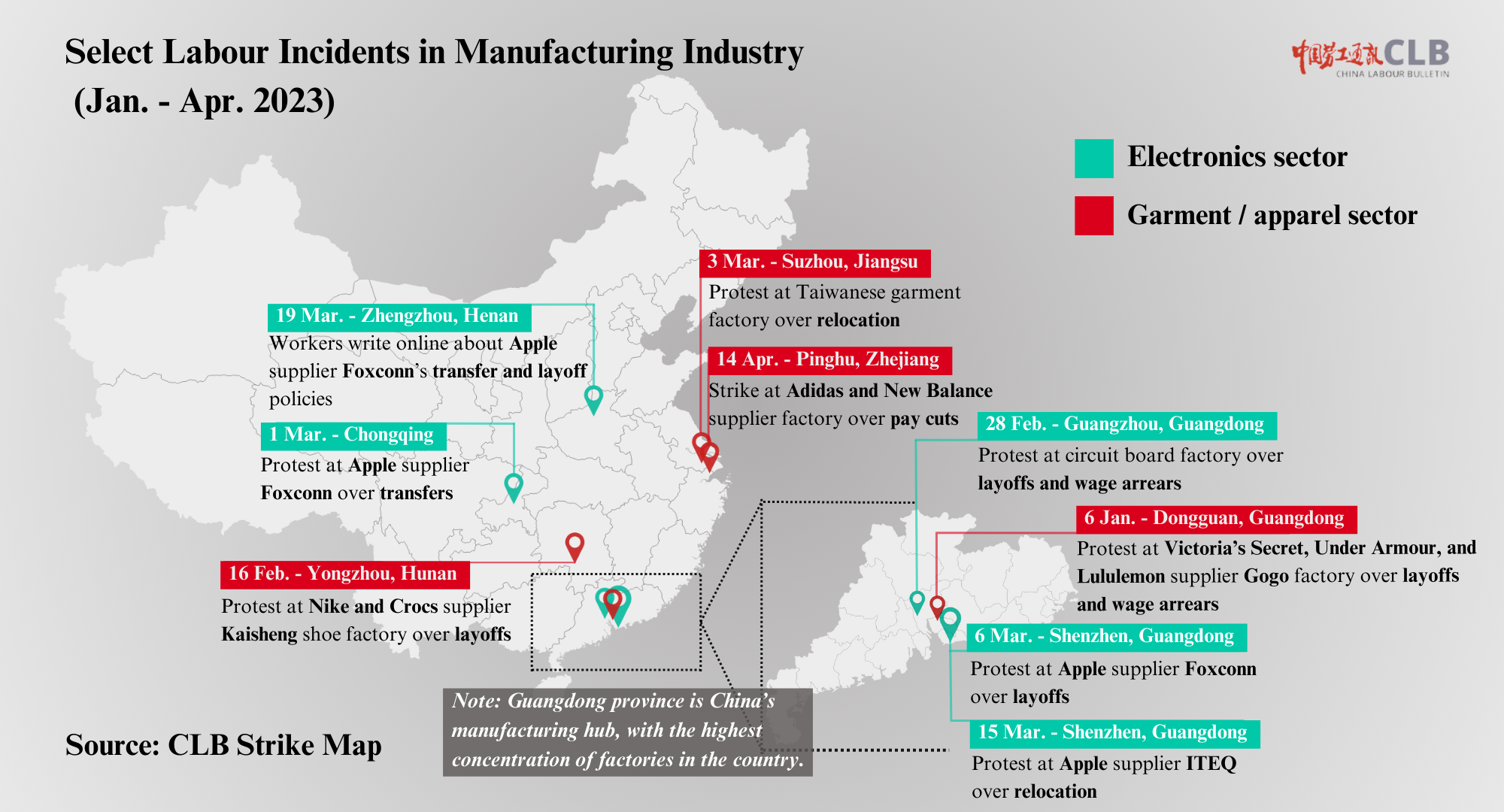

These protests are concentrated in the export-oriented electronics industry, followed by garments and apparel, toys and the automotive sector. Workers are protesting over unpaid wages and benefits as well as layoffs and relocations, requesting economic compensation for these employment changes.

Chart: Number of manufacturing protests recorded in the CLB Strike Map (October 2022 - March 2023)

Recent trade data indicates that global economic conditions are negatively affecting China's export economy. As a result, factories and suppliers are changing their practices to sustain their businesses. For example, in the consumer electronics industry, midstream factories producing circuit boards are lowering their prices to secure orders, causing the price of many products to drop 10-15 percent. Major downstream electronics manufacturers, such as Wistron and Pegatron, are also facing a drop in orders. Wistron has decided to close its factory in Taizhou, while part of the Pegatron factories in Kunshan are closing down and moving to India.

What do China’s labour laws have to say about workers’ rights during mass layoffs, relocations, and shutdowns?

China’s 2008 Labour Contract Law contains protections for employees through written employment contracts. The law distinguishes ordinary hiring, firing, and resignation from circumstances that affect a large portion of an employer’s workforce. Essentially, any major business changes that affect employment, pay, or place of work require the company to pay economic compensation to workers.

For mass layoffs or business closure, employees are entitled to severance pay according to the number of years worked at the company (Arts. 46-47). In addition, the employer must give 30 days’ notice (Art. 41), and the employer must hold consultations with all workers or the trade union as well as make a report regarding the layoffs to the local labour department (Art. 41). When production is merely suspended, this still requires compensation (Art. 38).

Business relocation is not specifically mentioned in the law, but several provisions apply. First, the place of work is a fundamental term of the labour contract (Art. 17). Therefore, a change of work location requires a renegotiation of the contract (Art. 35, Art. 40). If a factory relocates, this unilateral change to the contract terms - or termination of it - means the employee should be compensated. An exception is if the relocation is within the same administrative region and the workers can reasonably travel there.

Photograph: humphery / Shutterstock.com

For workers hired through labour agencies rather than directly with the factory, their labour protections are more precarious. The Labour Contract Law requires employers to sign contracts directly with workers to ensure workers' legal protections (Arts. 10-12), so the rise in agency labour has become prevalent as a way to avoid some requirements of the law. The law was amended in 2013 to add provisions on agency labour (Art. 57-67), and, the following year, China’s Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security released the Interim Provisions on Agency Labour, which put in place some measures to ensure the principle of equal pay for equal work, that no more than ten percent of a labour force could be agency labour, and that the positions had to truly be temporary, auxiliary, or substitute job positions rather than hiring de facto full-time employees this way.

Only when the employer unilaterally changes the terms of labour does the employer owe workers compensation. Therefore, some companies have found ways to compel employees to resign to try to avoid the provisions of the law. Further, China's manufacturing sector has been facing a labour shortage, and use of agency labour is common in some cases CLB has observed since late last year, complicating the labour rights situation in the manufacturing sector at this time.

How have employers been attempting to dodge China’s labour laws when making business decisions?

Electronics factories transfer workers or urge them to resign

In the electronics industry, moving production lines among a company’s various factories is a common pretext to force workers to resign.

As a result of reduced production demand from Apple, Foxconn conducted an "employee transfer program" in early March. Workers were asked to either accept transfer to other factories or resign. Some workers viewed this as a way to lay them off without compensation. On 1 March, an online video shows Foxconn workers in Chongqing having a conflict with management. On 6 March, a group of Foxconn workers in Shenzhen staged a demonstration. According to a 19 March post on social media, Foxconn in Zhengzhou - the site of a major labour rights crisis last autumn - transferred employees to other cities in China and even to India, and workers who refused to transfer were laid off.

On 15 March, employees of Taiwanese company ITEQ (Lianmao Electronic Technology Co.) in Guangzhou complained that the company called the relocation an "industrial upgrade" and required workers to accept the transfer. For those who refused, workers were threatened that they would be considered absent from work for three days and automatically considered to have resigned. Workers wrote online that if they insisted on not moving, the company said it would block them from entering the factory by disabling their entry cards, force them to take three months’ leave, and require them to be on call to return to work at any time.

Factories shut down with outstanding financial obligations to workers

Through unpaid wages, some companies pass on to workers the losses caused by reduced orders. Wage arrears is the most common cause of worker protests across sectors in CLB’s Strike Map.

On 15 February, Nansha SAntis Substrates Ltd., in Guangzhou, announced that it would cease its circuit board production on 28 February because of a continuous decline in orders and low funds. The company had already been defaulting on paying workers’ housing provident funds for over two years and social security payments since early this year. At the time of the announcement, workers’ wages had been unpaid for four months.

The company claims to have reached an agreement with employee representatives regarding compensation and the termination of labour relations. But workers protested to the district government, claiming that the factory forced termination of their labour contracts, refused to pay compensation, and delayed the payment of wages and housing provident funds. Videos online show a row of police officers separating protesting workers from government buildings.

Reputable factories in garment sector lay off workers, cut wages or shut down

Garment and apparel factories are also seeing an increase in closures and relocations. On 10 January, Dongguan Gogo Garment Manufacturing Ltd, the largest underwear factory in the region, announced closure and requested that workers leave the factory premises within a week. The factory has a 30-year history and was known as a stable employer. But recently, the workforce had shrunk from a peak of over 10,000 workers to just over 1,700 at the time of its closure. Even with this smaller workforce, the factory was unable to pay workers’ wages toward the end. This factory was producing for Victoria’s Secret, Under Armour and Lululemon at the time of its closure.

On 16 February, workers at Kaisheng Shoe Factory in Qiyang, Hunan province, went on strike. Workers were being laid off and suspected that the factory was planning to relocate. In 2011, the factory employed nearly 4,000 people, but recent supplier data shows a recent drop to about 3,400 workers. As of March 2023, workers were reporting further layoffs, and an employee posted online that she only received 300 yuan in monthly wages, indicating that the downsizing is not over. This factory produces for brands such as Nike and Crocs.

Jiaxing Quang Viet Clothing Co. Ltd., a Taiwanese-invested clothing factory in Pinghu, Zhejiang province, also saw a strike on 14 April. Over 100 workers negotiated on-site with management, complaining that their monthly salary of 2,000 yuan was too low and did not keep up with the cost of living. According to a recruitment ad, the factory has four production workshops, 70 production lines, and more than 2,500 employees. The company claimed in its ad that skilled workers can receive an income of up to 10,000 yuan per month, which includes various bonuses. However, due to reduced orders, working hours have dropped and the actual monthly salary reported by workers is only 2-3,000 yuan. This factory produces jackets, sportswear, and casual wear for Adidas, Nike, and other brands.

What avenues exist for workers to increase their bargaining power?

The number, scale, and demands of workers' actions collected in CLB’s labour database speaks volumes for the inhospitable environment for workers to increase their bargaining power vis a vis employers and local interests in sustaining capital, on even the most basic rights guarantees under China’s laws. Meanwhile, China has one massive official trade union, the All-China Federation of Trade Unions (ACFTU). Organizing by workers outside this official union structure is unlawful, and workers face barriers in union membership and may have low trust in the union to effectively represent them.

The ACFTU has vast resources and a mandate to represent the rights and interests of workers in China, but based on CLB’s years of observations and interactions with the ACFTU, the union does not readily act as a true union should. Instead, the ACFTU at its various levels performs displays of loyalty to the party and state and acts to ensure economic and social stability, activities which often conflict with its role to represent workers. However, high-level calls for reform of the union into a more representative body and recent attention by the union on vulnerable groups of workers shows promise.

But in these recent cases of worker strikes and protests in China’s manufacturing sector, the union has largely been absent. For example, when the requirements of China’s labour laws are violated and workers strike and protest for their rights, the local trade union could step in and negotiate to ensure that employers comply with the law and involve local governments in seeking a viable solution. In fact, in many of these cases, the workers strike after months or years of violations, showing that the local unions have wasted time in not understanding workers’ concerns. The strikes represent an escalated situation in which workers believe they have no other recourse.

For example, the Nansha district federation of trade unions in Guangzhou, where the Nansha SAntis Substrates factory is located, has touted its mediation committee that has established a warning mechanism for labour disputes. However, this committee did not play a role in the strike at SAntis Substrates. Instead, just ten days before the strike, the street-level federation of trade unions in Nansha held a congress proposing that the union “act as a bridge and link between the party and the masses,” with a service-oriented mindset toward workers to prioritise their voices. In practice, the union has sorely missed the mark.

In the garment sector, unions may intervene, but only after workers have been pushed to their limit and take strike action. In these situations, the union sees its role as maintaining social stability and stopping the strike, rather than representing workers. For instance, union officials in Jiaxing told China Labour Bulletin that workers at the Jiaxing Quang Viet factory had a “misunderstanding” about their reduced wages, overlooking the fact that the union is lawfully enabled to negotiate with management, request that the factory disclose its order status, and - as CLB suggested to them - to join stakeholders together to urge the brands to fulfil their contracts.

Photograph: humphery / Shutterstock.com

In fact, when external factors such as the pandemic, global purchase patterns, and China’s domestic economy are involved, the union has tools to advocate for a range of local and regional stakeholders. Unions should proactively understand the operating conditions of enterprises in their respective regions, and - when economic conditions change - organize workers to negotiate with companies that have shown preliminary signs of wage arrears and social security arrears, reducing the negative impact on workers’ rights during economic downturns.

What is the role of international companies and brands supplying from China?

Based on CLB Strike Map data, some industry trends have become apparent from workers’ reactions to employers’ decisions. Workers are generally aware of their rights under the Labour Contract Law and will protest against what they perceive as forced resignations used to avoid paying compensation for mass layoffs, relocations and shutdowns. Many of these factories are in economic straits and have difficulty paying salaries and benefits, let alone proper compensation under the law. Some of these factories are reputable for having long followed China’s labour laws, paying relatively decent wages on time, and being long-term stable employment, but as China’s economic conditions and global production patterns change, it should not be left to workers to fend for themselves now.

CLB will continue to urge ACFTU officials to better represent workers, including through strategies such as organizing negotiations with a variety of stakeholders. Yet, in the political and social environment that disallows workers’ right to freedom of association - and where the national union has not adequately represented workers’ interests - brands arguably have a high duty to ensure that workers’ rights are not violated along their supply chains and that there are conditions for workers’ voices to be heard.

Further CLB reading:

- Global South workers have a new solution in light of brands’ unpaid Rana Plaza debt (May 2023)

- What You Need to Know About Workers in China: Workers’ rights and labour relations (last updated June 2020)

- Relocating factories find loopholes to avoid paying compensation to workers (April 2023)