Photograph: XiXinXing / Shutterstock.com

Letter from the Editors

This year’s Double Eleven shopping holiday just passed with little fanfare. The market was cooler this year, and e-commerce giants faced more competition from sales on short video platforms. In the past, CLB focused on the pay and labour conditions for package couriers and live-video streamers during Singles Day. Their labour conditions have not improved, but this year the story is more about the slumping economy and its relationship to the job market, workers’ wages and other indicators.

In our March 2022 report, Reimagining Workers’ Rights in China, CLB makes the connection between long-standing workers’ rights and livelihood issues and state campaigns such as “common prosperity.” In fact, it was China’s giant tech companies and their executives - those now reeling from the recent Double Eleven disappointment - who first made flashy donations to the cause of common prosperity.

Where did those donations go? Wouldn’t it have been more effective for those companies to ensure their own workers’ rights are protected, including fair pay for their labour? From factory workers producing goods, to tech workers doing overtime, to couriers delivering products to customers budgeting their salaries, everyone is connected.

Thanks for reading!

CLB Editors

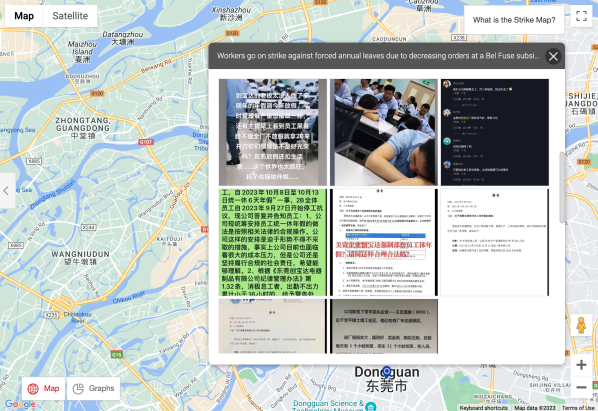

Strike Action

Month-on-month increase in worker actions. CLB’s Strike Map recorded 225 worker collective actions in October, not only the highest monthly tally this year but also the highest since 2017. Comparing the data with September 2023 figures, the increase is mainly attributable to activity in China’s construction industry, which saw a 25 percent increase in incidents in October. The proportion in other industries has remained fairly stable.

Construction workers’ wage arrears. Workers are striking and protesting over unpaid wages on housing and infrastructure projects. At residential construction sites, the number of incidents rose from 45 in September to 59 in October. These occurred at major property developers’ sites, including seven at Country Garden properties across the country. Vanke Group saw four incidents. Evergrande Group had two incidents. For infrastructure projects, our map logged 17 incidents, up from 12 last month. These occurred on high-speed rail, highway, and pipeline projects in central and northern China.

Platform truck drivers go on strike again. On 16 October, Huolala (Lalamove) drivers in three cities went on strike against a new order model. In Foshan, Guangdong province, and Hengyang, Hunan province (see image, above), drivers parked their trucks outside Huolala offices, blocking the entrances. In Chengdu, Sichuan province, over 100 drivers gathered at a Huolala pickup point to negotiate with management. The new order model began in March 2023 and allows drivers to bid for customer orders based on the quantity of goods transported. Drivers see this mechanism as a disguised price reduction that pits drivers against each other, and they face safety risks on the road because of increased pressure. Drivers resisted by placing fake orders on the platform or simply not accepting any orders. On 3 November, the authorities called in Huolala and asked them to take “targeted measures” to “comprehensively rectify” issues. See CLB’s previous analysis of Huolala strikes and regulatory reactions in November 2022 and May 2023.

Workers’ Voices

Does the boss think that rank-and-file workers will more easily accept a bad fate, or that we are easy to deceive? They always ask workers to think from the boss's side, but are the bosses also thinking from the workers’ side? If we all have in mind the same thing [laying off workers], why make it so complicated and annoyingly awkward?

Many factory workers in China have been thrown into uncertainty this year. With declining orders and other economic challenges, factories are looking for ways to cut costs. This includes reducing workers’ hours, relocating to lower-cost regions, and shutting down altogether.

But these management plans are not transparent, and workers feel they are being strung along. It also affects the size of their economic payout when their contracts are unilaterally terminated. And some factories are attempting to skirt the law by encouraging and incentivising voluntary resignations.

That was the case this autumn at Dongguan Transpower Electric Products Co., Ltd. (TRP Connector), a sister factory of Zhongshan Wing Ming Electric Co. Ltd., which we also wrote about. These two factories are under a consolidation plan by U.S.-listed BelFuse, and workers have not been offered a transfer to BelFuse’s new Guangxi facility.

In both of these cases, workers took to social media to speak out about their vulnerability and uncertainty this year, also seeking help from the local labour departments. But their power against corporate interests is small, and they can only hope to be treated fairly and according to the law.

Worker Representation

China’s official trade union follows a rigid hierarchical structure in which its bureaucracy often prevents it from fulfilling its basic mandate to represent workers. This was the case when an electronics factory worker died in his dormitory in Suzhou after working 13 consecutive night shifts.

The worker’s family sought for the company - Qisda, headquartered in Taiwan and producing for HP and Dell - to compensate them for the death as a workplace injury. The Xu family entered negotiations with the company, but Qisda insisted that it was not responsible for the death of 23-year-old Xu and offered only “humanitarian aid.”

When China Labour Bulletin called the Shishan Hengtang street-level union in Suzhou on 19 October, the union official told us plainly that when they found out there was no genuine enterprise union at the Qisda factory, the local union exited negotiations:

I was at the negotiation scene [with the Xu family]. Then we looked into our internal system and found no record of an enterprise union at Qisda. The company probably created one when there was a campaign to establish a lot of unions years ago, but it’s one that is not functioning normally. We cannot find it in our system now. Therefore, we did not participate in their subsequent negotiation and mediation process.

Of course, workers and their families need representation the most when there is no enterprise union; otherwise, what is the local union office even for?

Safety First

Sunday will mark the thirty-year anniversary of the tragic Zhili fire in Shenzhen. On 19 November 1993, a huge fire at the Hong Kong-owned Zhili Toy Factory killed 84 workers and injured dozens of others. The Zhili fire represents the systemic lack of work safety protections of that era.

Although the number of workplace accidents has dropped over time, China’s official data shows that over 2,000 workers still die on the job each year from industrial and commercial accidents, and major accidents occur with regularity. CLB previously covered the 22 November 2022 fire at a garment factory in Anyang, Henan province, that killed 42 workers.

In a forthcoming article, CLB will analyse the official responses to these two accidents, plus the root causes of workplace hazards and recommendations to save workers’ lives. For more information about work safety in China, see our explainer.

CLB in the News

CLB’s Strike Map data and our analysis on issues facing food delivery riders was cited by The Economist to support new research by Bo Zhao of Fudan University in Shanghai and Siqi Luo of Sun Yat-sen University in Guangzhou. Their research examines how low-key activism that does not raise public attention is affecting platforms’ service.

Drivers and couriers have pressed for improvements, holding around 400 protests in the past five years, says China Labour Bulletin, an NGO in Hong Kong.

It helps when the public gets involved. In 2021, a company called Ele.me said it could pay only 2,000 yuan ($273) in compensation to the family of a delivery worker who died on the job. After a backlash on social media, the company agreed to cough up 600,000 yuan. Later that year, the government demanded that delivery companies improve working conditions for drivers and couriers. But little has actually changed, says China Labour Bulletin.