On 14 August 2023, a 23-year-old migrant factory worker died in his dormitory after working 13 consecutive night shifts under a labour dispatch agreement at the Qisda electronics factory in Suzhou, Jiangsu province.

According to China Business Daily, Xu Xiao is from Yunnan province. He began working at Qisda only in July of this year, and he was in good health with no underlying medical conditions.

Xu’s older brother spoke to the media, saying his brother dropped out of school early to work:

Our parents died of illness when we were very young. My brother and I are orphans. It was my grandmother who worked hard to raise us… She is 75 years old, and I have kept the news of my brother's death a secret.

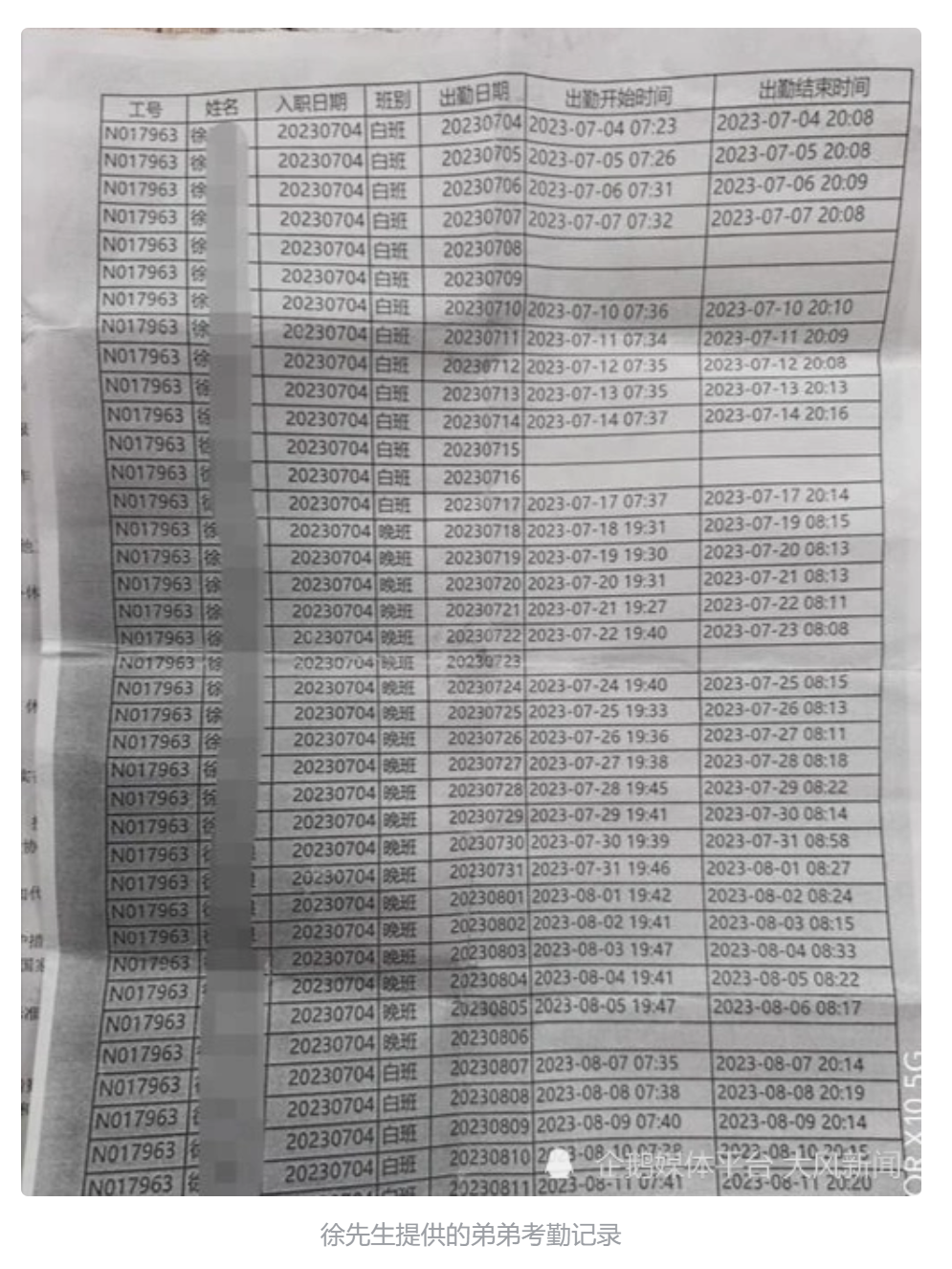

Work attendance records show that Xu’s schedule was irregular, but from 24 July to 5 August, he worked over 12 hours every night, from 7:40 pm to 8:20 am, some days clocking out as late as 8:58 am.

Xu’s brother posted online an image recording the shifts Xu worked since he began employment at Qisda on 4 July 2023. From 24 July to 5 August, Xu worked 13 consecutive night shifts. Source: China Business Daily

On 12 and 13 August, Xu was finally granted days off. When he didn’t show up for his scheduled shift on 14 August, he was discovered dead in his dormitory. Homicide and substance abuse were ruled out as causes of his death.

Xu signed a labour contract with the Tiantong branch of the Suzhou Lanlingtong Network Technology (苏州蓝领通网络科技有限公司) agency for a term of two years, starting 4 July 2023, to work at Qisda.

Qisda Optronic (Suzhou) Co. Ltd. (苏州佳世达) produces LCD monitors and projectors and wireless bluetooth modules for Dell and HP. The company’s headquarters are in Taiwan, and in addition to the facility in Suzhou, Qisda has a location in Vietnam.

According to Qisda’s 2022 ESG report, the Suzhou factory has 4,763 workers and made 1,645 new hires. Out of 2,764 reported new hires in 2022 at the Taiwan, Vietnam, and Suzhou locations, 46 percent were “indirect hires.”

China Labour Bulletin gathered this incident and related online sources in our Workplace Accident Map, and we called the street-level office of China’s official trade union in Suzhou in late October 2023 to learn more information.

Qisda workers report harsh working conditions, excessive overtime and poor dispatch labour practices

Workers at Qisda report that their base salary is about 2,100 yuan (U.S. $285) per month, and in the busy seasons they can earn about 3-4,000 yuan per month because of overtime pay and other compensation.

Online, past and present Qisda workers have a lot to say about the working conditions at the factory. In addition to poor management and less-than-satisfying food at short meal breaks, they also have complaints about excessive overtime and sneaky practices of labour dispatch companies.

A sampling of worker reviews left on the “Drifting Frog” website that rates employers in China shows some common negative experiences at Qisda:

Many people quickly cycle through at Qisda. Those who go to work at Qisda are tricked by intermediaries [labour dispatch agencies]. It is very tiring because we need to work in a standing position, and the overtime work exhausts us… It is extremely difficult to ask for sick leave, because you need a medical form from the hospital. And even with this medical proof, you can only take two days at most.

Working at Suzhou Qisda is so exhausting. When it’s busy, you work 13 hours a day. The assistant foreman inhumanely urges you to work. You are not allowed to rest for a minute.

Long working hours in a standing position, often having to work two shifts! It’s very tiring.

Let me tell you whether it is true that the factory pays 300 yuan a day. First of all, they [Editor’s note: likely referring to a labour dispatch agency] didn’t tell you about many expenses. For example, out of the 300 a day, insurance costs a few dozen a month, at least. Food and accommodation are said to be free, but in fact they are deducted from the salary, which is at least 20 yuan a day.

These complaints are of a systemic nature, bolstering Xu’s brother’s claim that the death was a work-related injury and the family is owed compensation.

Photograph: Fishman64 / Shutterstock.com

But the Qisda factory does not have a functioning enterprise union to represent workers about these ongoing issues. This lack of a factory union even created obstacles for the regional offices of China’s official trade union when it tried to intervene in the negotiations between Xu’s family and the factory.

When China Labour Bulletin called the Shishan Hengtang street-level union in Suzhou on 19 October, the union officer told us plainly that when it found out there was no genuine enterprise union at Qisda, it exited negotiations on this incident:

I was at the scene of the negotiation [with the Xu family]. Then we looked into our internal system and found no record of an enterprise union at Qisda. The company probably created one when there was a campaign to establish a lot of unions years ago, but it is one that is not functioning normally. We cannot find it in our system now. Therefore, we did not participate in their subsequent negotiation and mediation process.

CLB found that the enterprise union at Qisda was said to be established in 2012 during a large-scale campaign. We suggested to the union officer that the street-level union work with the company to establish a functioning enterprise union.

We also found that the street-level union had conducted work safety exercises at Qisda this past May. We suggested that an enterprise union could start with Xu’s case to negotiate on health and safety matters including maximum overtime hours in accordance with the law, as well as working conditions and illegal use of labour dispatch at the factory.

Xu’s family claims a workplace accident, but Qisda denies responsibility and offers only humanitarian aid

Xu’s family requested 1.5 million yuan (U.S. $205,000) in compensation for Xu’s death as a workplace injury. But the Qisda factory called the death an “accident” unrelated to work and insisted that the workplace complies with all relevant laws. Further, Qisda raised that any liability should be placed on the labour dispatch agency, not on Qisda.

Unfortunately, the Xu family never had the opportunity for a legal decision on whether Xu’s death was a workplace accident. Xu’s brother said they could not afford an autopsy to obtain evidence about the cause of death.

However, Qisda still claims that its practices comply with China’s domestic laws and regulations. A company representative told the media that Xu “was an adult” and had “cooperated with the company to work overtime” in compliance with the law.

However, based on Xu’s work schedule, Qisda has violated the Labour Law’s basic provisions on a 40-hour work week (Art. 36) plus a maximum of 36 hours of overtime per month (Art. 41).

Contrary to Qisda’s statement, any adjustment beyond the standard workweek must be negotiated not only with the worker but also with the union, and in no case can exceed the legal maximum (Art. 41). This adjustment must also be “under the condition that the health of labourers is guaranteed” (Art. 41).

Photograph: Teerapong mahawan / Shutterstock.com

Further, Xu was a dispatch worker for a term of two years. Qisda’s substantial reliance on labour dispatch may violate China’s Provisional Regulations on Labour Dispatch, which stipulate a maximum of ten percent of the labour force comprising dispatch workers (Art. 4).

Further, the ongoing reliance on labour dispatch may indicate a violation of China’s Labour Contract Law, which states that labour dispatch must only be for legitimate needs such as temporary, auxiliary, and substitute jobs (Art. 66), rather than for ordinary hiring. The dispatch agency and the “labour-receiving unit,” aka the factory, have joint and several liability for violations of the law (Art. 92).

Finally, if a workplace accident - which is under a no-fault legal framework - cannot be certified based on the available information, the family’s only other option would be to utilise China’s civil law and bring a tort claim against the factory. The legal burden on the plaintiff to establish a cause of action is high, and the process would also be expensive and time-consuming for the family.

According to the media, Qisda initially offered the family only about 50,000 yuan in humanitarian assistance, which the family rejected. The family then asked for 280,000 yuan, and the factory counter-proposed with about 100,000 yuan.

When China Labour Bulletin called the street-level union on 19 October, the union official told us that the family had accepted and received over 200,000 yuan from Qisda.

China’s workers need new solutions to ensure safe working conditions, and stronger mechanisms linking overtime work to health and safety issues

China’s domestic legal framework lacks strong enough enforcement to adequately protect workers’ rights against systemic violations. In addition, the link between illegal overtime and workplace health and safety requires reinforcement.

However, China’s official trade union has the mandate to represent workers, and it could take more steps to become involved in negotiations with companies to press for better working conditions. In addition, the union could use other tools, like calling on stakeholders across the supply chain to step in to guarantee workers’ health and safety and other rights.

Such a process would be in the interest of many stakeholders, including brands and corporations who are committed to upholding workers’ rights in their supply chains, factories that will benefit from increased productivity as a result of improved health and safety conditions for workers, local governments that can rely on responsible local investments, and workers as the ultimate beneficiaries of better labour rights conditions.

Further CLB reading:

- China’s toxic work culture under fire again in Beijing (March 2021)

- What You Need to Know About Workers in China: Work safety (last updated September 2021)

- Migrant courier dies from overwork in Beijing, local unions cite jurisdictional constraints in helping platform economy workers (April 2023)