At the end of 2019, there was a huge public outcry in China over reports that Li Hongyuan, a former employee of Chinese tech giant Huawei, had been detained for eight months by the authorities in Shenzhen apparently at the behest of Huawei after he asked his former employer for severance pay and a yearly bonus.

For many middle-class professionals in China, the case confirmed a growing sense of unease and the realisation that, in the eyes of their employer, they were nothing more than a resource to be exploited and then discarded. What happened to Li Hongyuan, it seemed, could just as easily happen to them.

Tens of thousands of well-paid professionals in the tech industry lost their jobs last year as intense competition for market dominance combined with a slowing economy in China led to the collapse of hundreds of tech start-ups, including several so-called unicorns. Many employees, such as those at US tech company Oracle in Beijing, had to take prolonged collective action in order to get decent severance pay before being laid off.

Those employees who still had a job rebelled against the excessively long work hours (9.am to 9.pm, 6 days a week) demanded by their employer and openly rejected the corporate “wolf culture,” first developed by Huawei, that stressed loyalty and dedication to the company above all else. A survey of white-collar workers published towards the end of the year confirmed that younger workers felt little sense of loyalty to their employer (most left within three years). The vast majority of respondents said respect and fair treatment should be the most important component of any corporate culture, while only a small minority said they were still willing to accept “wolf culture” in the workplace.

Dissatisfaction among younger workers at the current state of labour relations was further heightened in April last year with the revelation that China’s main state-backed pension fund could be completely depleted in 2035, just when those born in the 1980s were hoping to retire.

It could be that 2019 marks a fundamental shift in the values of white-collar workers in China. Many younger workers are no longer willing to work long hours nor accept the kind of hardships their parents endured in order to chase illusory dreams of a better life; instead they focus on decent pay for decent work and a healthy work-life balance.

For most blue-collar workers, however, there were more basic concerns last year like just getting paid.

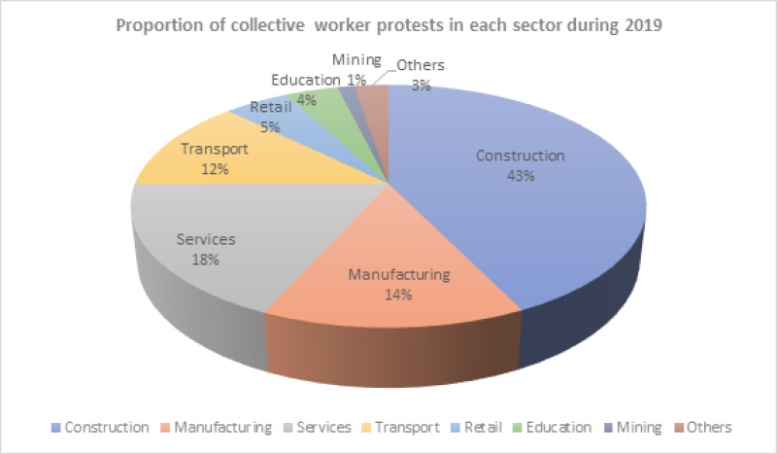

Of the 1,386 collective worker protests recorded on China Labour Bulletin’s Strike Map last year, 1,159 (about 84 percent) concerned demands for payment of wages in arrears. And once again, it was the construction industry, which accounted for 43 percent of all protests, where the problems were the most severe. Despite repeated government promises to solve the problem of wage arrears for construction workers, a staggering 99 percent of all incidents recorded last year were related to the non-payment of wages. There are still deeply ingrained and systemic problems in the construction industry that have become even more apparent as the economy slows and credit becomes more difficult to obtain. CLB’s 2019 report on the construction industry argues that the only way out of this quagmire is to create a new system of sectoral trade unions that can ensure decent pay and working conditions for construction workers through collective bargaining with industry representatives.

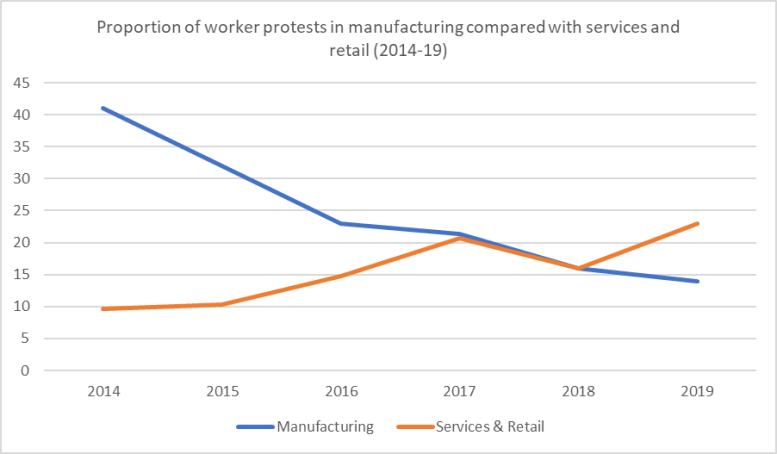

One of the most noticeable trends in the sectoral distribution of worker protests has been the growth of collective protests in the burgeoning service sector and the relative decline of factory worker protests. Over the last six years, the proportion of factory worker protests has steadily declined from a high of 41 percent in 2014, while protests by service and retail sector workers have risen from a low of 9.7 percent in 2014 to 23 percent last year. See graph below. The service sector increase was particularly sharp last year, rising from 13 percent to 18 percent of all incidents.

It is clear that the focus of worker unrest in China is shifting away from factories, many of which closed down or relocated during the last decade, and towards shop workers and sales agents, catering and hotel staff, street cleaners, hospital staff and employees in the leisure industry. This trend was exemplified by the large number of collective protests of employees at the hundreds of gyms and fitness centres that closed down in China last year. Workers in service and retail industries are often poorly paid, work long hours and run a high risk of suddenly losing their job because of widespread business in a highly competitive market. Even professional footballers in China’s struggling lower league teams endured months without pay before finally staging protests of their own. One player at Hainan FC, owned by real estate developer, R&F Group, compared their situation to migrant construction workers who had been cheated out their wages by a labour contractor and were now desperate to get paid before the holidays.

Transport workers are still a significant force in labour activism despite a drop in the number of protests last year. Food delivery workers and couriers were at the forefront of transport worker protests although there was, in addition, a sudden outburst of large-scale and sometimes violent protests by taxi drivers in December. The December protests proved that drivers’ long-standing grievances over competition from unlicensed cabs, government regulation and cab company management abuses have never really been resolved and that it only needed a small spark to reignite the protests that had been on the decline since 2017.

The taxi driver protests were unusual in one respect however in that they involved several hundred, even thousands of participants. The vast majority of protest actions last year were small-scale and short-lived, designed to attract attention and demand a resolution of their grievances rather than cause widespread social and economic disruption. A total of 1,297 protests (94 percent) involved less than 100 people, with only a handful comprising more than 1,000 workers. By way of comparison, 7.2 percent of all protests in 2014 involved more than 1,000 workers.

Perhaps because of the relatively small-scale nature of last year’s protests, the police only actively intervened in 173 incidents (12.5 percent) and made arrests in just 30 cases (2.1 percent). In 2014, when protests were dominated by large-scale factory disputes, police intervened in about 27 percent of all disputes recorded on the Strike Map and made arrests in about eight percent of all cases.

About 79 percent of last year’s protests (where ownership type could be determined) occurred in domestic private enterprises, confirming the trend identified in last year’s analysis of worker activism in which labour disputes were overwhelmingly concentrated in the domestic private sector rather than state-owned enterprises or foreign companies. That said, pay and working conditions for many employees at state-owned enterprises are getting worse as companies continue to use outsourced labour rather than hire workers on formal employment contracts. There was a major protest over this issue by workers at FAW Logistics in Changchun in December but generally workers at SOEs find it more difficult to organize given the political sensitivities involved. And it is likely to become even more difficult this year once Communist Party officials start playing a larger role in SOE management: worker protests could be seen as an attack on the Party, not just the employer.

Location of worker protests in China by province in 2019

In terms of geographic distribution, worker protests occurred in every province and region of China, although the heavily urbanised provinces of Guangdong, Henan, Jiangsu and Shandong remained the main centres of unrest. Guangdong accounted for 10.5 percent of all protests last year and 24 percent of all protests in the manufacturing sector. Many factory protests in Guangdong were related to closures or relocation, indicating that the Sino-US trade war is having an adverse impact on the province’s export-orientated manufacturers. At the other end of the scale, there were only four protests in the whole of last year in the far western region of Xinjiang, compared with 33 incidents in 2015. This drop is partly due to the difficulty of getting information out of Xinjiang but it also indicates the government’s minimal tolerance for worker unrest in the region. The authorities in Xinjiang last year embarked on widespread campaign to mould Muslim minorities into loyal blue-collar workers to supply Chinese factories with cheap labour.

While there were relatively few police interventions in collective labour disputes generally, the government intensified its ongoing crackdown on civil society labour activists. The year began with the detention of three labour activists and citizen journalists from iLabour who had been helping migrant workers with occupational disease defend their rights. Around the same time, Shenzhen police detained five activists including well-known campaigners Zhang Zhiru and Wu Guijun. Prominent anti-discrimination activist Cheng Yuan, and his two colleagues, Liu Dazhi and Wu Gejianxiong, were detained by the authorities in Changsha in July, and several well-known social workers who had been helping migrant workers in Beijing, Guangzhou and Shenzhen were detained in coordinated raids in May. In late October, #MeToo activist and journalist Huang Xueqin was also detained by the authorities in Guangzhou. Finally, in late December, sanitation workers advocate Chen Weixiang and two associates were administratively detained in Guangzhou for 15 days. Some of these activists were quietly released without charge while others have been formally charged and await trial.

Chen Weixiang’s case once again focused public attention on the plight of sanitation workers who struggle with low pay, long hours, dangerous working conditions and exploitative management regimes, exemplified by one company in Nanjing that forced workers to wear GPS trackers in order to monitor their movements and issue an alarm if they remained stationary on a break for more than 20 minutes. There was an upsurge in strikes and protest by sanitation workers during the summer months last year, with a total of 18 incidents recorded during the year as a whole.

Likewise, the iLabour detentions highlighted the terrible toll the deadly occupational disease pneumoconiosis has taken on China’s migrant workers, as well as their continuing struggle for justice. Former miners and construction workers from all over China took collective action last year to demand fair compensation and proper medical treatment. While some of these protests led to repression and arrests, others were successful and, at the end of the year, the central government pledged to make sure all workers in industries with a high risk of occupational disease will be covered by work-related injury insurance within the next three years. While the government initiative was in essence a restating of existing laws and regulations, it does at least signal a growing willingness to tackle the pneumoconiosis epidemic.

Work safety in general emerged as an issue of growing social concern last year after an explosion at a chemical plant in Jiangsu killed 78 people and injured another 600. China’s media soon highlighted the repeated safety violations at the plant, and the same pattern of inadequate regulation emerged in just about every subsequent fire and explosion or mine collapse during the year. There were several high-profile coal mine accidents in 2019 including an explosion at a mine in Shanxi on 18 November that killed 15 miners. Media reports claimed the Shanxi mine operator had been “blinded by greed” and exceeded numerous safety protocols in expanding the mine without ensuring proper ventilation, leading to the build-up of gas in the mine shaft.

Overall, work accident and death rates declined again last year, according to official figures, but it is clear that numerous problems remain and that workers and civil society are becoming increasingly intolerant of employers’ continual disregard of employee safety and the lack of effective government oversight.

For more stories, please see CLB's 2019 Year in Review, which features some of the key articles published last year.