photo credit: Gorodenkoff/ Shutter Stock

An analysis of CLB's 2024 labour data reveals a persistent disregard for workers' rights by employers, corporations, and government authorities, even as China's economic landscape shifts under the pressures of changing overseas investment, domestic demand, and evolving market structures across various sectors. Meanwhile, workers agitations in the manufacturing sector have surged to their highest levels in nearly a decade, despite a broader trend toward smaller-scale disputes, reflecting the transition to high-tech factories with fewer workers.

As companies prioritise cost-cutting measures and profitability strategies, workers' wages, social insurance, compensation, and living subsidies remain at the bottom of the list—if they are addressed at all. This growing tension underscores the widening gap between corporate interests and the basic rights of the labour force, painting a stark picture of the challenges facing workers in 2024.

In this report, CLB broadly analyses the raw data collected in our Strike Map and conducts a sector-by-sector analysis of issues affecting China’s workers and their rights. To know more about our methodology, please see our introduction to the Strike Map here.

Table of Contents

- Broad Trends

- Construction: Wage arrears remained high as property market slumped

- Manufacturing: Workers’ protests erupted as factory closures and relocation continued amidst slow growth

- Services: Local governments struggled to fund public services, wage arrears seen in traditional and new sectors while e-commerce strengthened and local governments struggled to fund public services

- Transport and Logistics: Cabbies protested to protect livelihood while ride-hailing drivers' earnings were squeezed

- Heavy Industry: Steel mills workers protested for wages and fair settlement compensation

- Conclusion

Broad trends

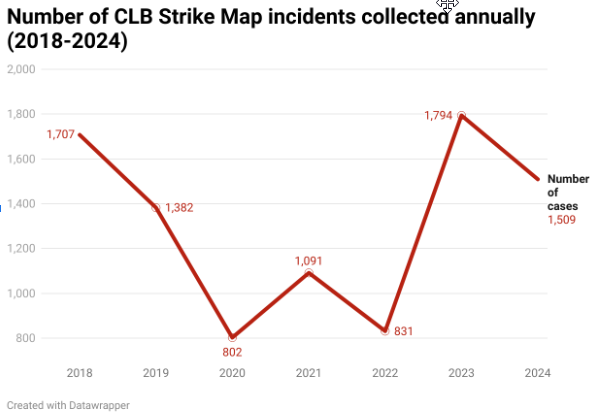

A total of 1,509 incidents were recorded in CLB’s Strike Map in 2024, a small decrease from 2023 (1,794 incidents) but still higher than the pandemic years (2019 to 2022). Worker unrest has remained at high-pre pandemic levels. 2023 was an exceptional year, as worker unrest came roaring back on the tail end of the pandemic.

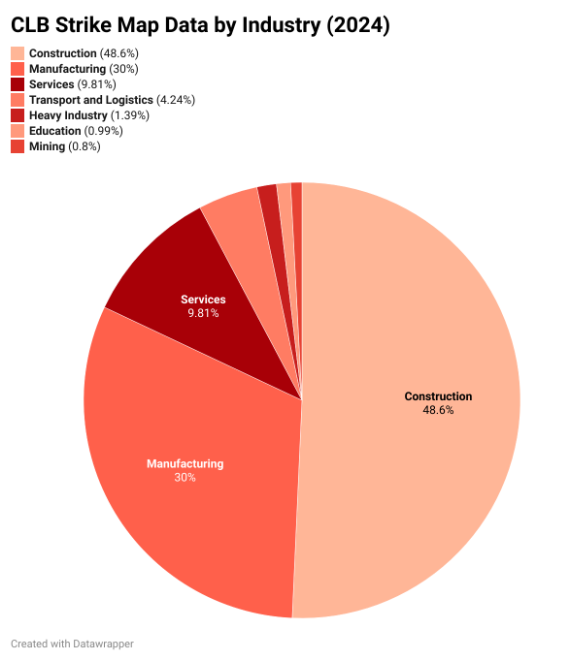

Among industries, the construction industry continued to see the most protests (733 incidents; 48.6 percent). While the total number of cases fell, those in the manufacturing industry (452 incidents; 30 percent) saw a rise from 2023. They were followed by the services industry (148 incidents; 9.81 percent), transport and logistics (64 incidents; 4.24 percent), heavy industry (21 incidents; 1.39 percent), education (15 incidents; 0.99 percent) and mining (12 incidents; 0.80 percent).

Incidents predominantly occurred in coastal provinces, but significant numbers of cases were also seen in inland ones. Guangdong continued to see the most labour rights-related incidents (346 incidents), while Shandong (106 incidents) and Zhejiang (101 incidents) recorded relatively high incidents. Notably, inland provinces such as Henan (80 incidents), Hebei (69) and Shaanxi (59) also saw many cases of labour rights abuses.

Source: CLB Strike Map, 2024

In 2024, China's economy was challenged by domestic as well as international developments. Domestically, interest and confidence in housing slumped, causing headaches for developers and construction companies.The expansion of e-commerce and ride-hailing platforms challenged the operations of existing companies. Changes in consumer behaviours required the services industries to adapt. Debts incurred by local governments meant that public services were affected. Internationally, when multinational companies decided to cut costs, factories in China were obliged to reduce or halt production. Given the trend of diversifying production away from China, the manufacturing industries have been getting affected gradually.

As the effects of all these economic challenges were passed on from companies and employers to workers, the latter saw their wages and social insurance going unpaid while in some cases, workers faced abrupt job losses without fair compensation as businesses shuttered or relocated. Unsurprisingly, wage arrears emerged once again as the top grievance, accounting for 88% of reported labour disputes.

In 2024, CLB recorded just four labour strikes involving over 1,000 workers, with more than 95% of reported incidents involving fewer than 100 participants. This trend has remained consistent since 2017 (see CLB analysis) and may reflect authorities’ continued efforts to prevent large-scale protests that could pose a risk to social stability. Probably the biggest strike of the year involved thousands of state-owned forest farm workers in Heilongjiang protesting for fairer working conditions last winter In 2024, China's economy was challenged by domestic as well as international developments. Domestically, interest and confidence in housing slumped, causing headaches for developers and construction companies.The expansion of e-commerce and ride-hailing platforms challenged the operations of existing companies. Changes in consumer behaviours required the services industries to adapt. Debts incurred by local governments meant that public services were affected. Internationally, when multinational companies decided to cut costs, factories in China were obliged to reduce or halt production. Given the trend of diversifying production away from China, the manufacturing industries have been getting affected gradually.

As the effects of all these economic challenges were passed on from companies and employers to workers, the latter saw their wages and social insurance going unpaid while in some cases, workers faced abrupt job losses without fair compensation as businesses shuttered or relocated. Unsurprisingly, wage arrears emerged once again as the top grievance, accounting for 88% of reported labour disputes.

Construction: Wage arrears remained high as property market slumped

Workers in the construction industry continued to see their wages remain unpaid in 2024, with residential projects being the main targets of protests. Although the Strike Map recorded fewer incidents in the construction industry in 2024 (733 incidents) than in 2023 (945 incidents), the sector continued to have the highest proportion of protests among industries. Across the country, Guangdong (134 incidents), Shandong (78) and Henan (46) – provinces that have seen significant investments in real estate and infrastructure in recent years – recorded the highest numbers of protests, a proportion similar to that in 2023 with Shanxi dropping out of the top 3. Among the types of projects targeted that CLB could identify, 50 percent were related to residential projects, around 30 percent in infrastructure projects followed by 20 percent in commercial projects.

In general, there was a lack of confidence from buyers in the real estate market in 2024. The sales of newly built properties decreased by 17.1 percent. At the same time, there was a 16.2 percent increase in the number of properties waiting to be sold. The year 2024 witnessed a decline in housing prices as prices for second-hand properties fell in all large and medium-sized cities; only Shanghai and Xi'an saw price increases for newly built housing. The overall figures indicate overproduction of housing.

As developers struggled with the depressed market conditions, the pressure was eventually transferred to workers. One of the major developers that had a tough year was Vanke. The company saw a slump in its bond pieces and was downgraded by rating agency Moody’s in March. The Strike Map recorded at least eight protests against unpaid wages related to Vanke. For example, construction workers in Shenzhen blocked the entrances of newly built residential apartments in December as they had not received any payment for the work they had completed the previous month. Meanwhile, buyers of the apartments were already receiving the keys for their new homes. In a social media post, commentators referred to the news about Vanke's financial problems implying that it would be unlikely that workers would receive their wages. The expressed frustration demonstrated the uncertainty that construction workers were facing given the declining property market. However, not long after the protest, the social media commentators said workers had received "a little bit" of their wages. Later, they said the wage issues were finally settled. Financial pressures on Vanke continue to grow in the new year as it is scheduled to repay more bonds than in 2024. Given the challenging real estate market, workers for other developers such as Country Garden and Evergrande also faced hardships in getting their wages paid in 2024 and this situation is expected to continue in 2025.

Unlike in the property market, investments in infrastructure increased by 4.4 percent nationwide in 2024. Investments in air transportation recorded a 20.7 percent increase and railway transportation 13.5 percent rise. However, investments in road transportation fell by 1.1 percent. Meanwhile, experts from a domestic think tank have reminded that local governments' spending on infrastructure might turn into inefficient investment and worsen the existing debt.

Photo: A video uploaded by workers during the strike at Guangzhou Baiyun Airport

One of the noteworthy workers’ protests in this sector was related to the expansion project at the Guangzhou Baiyun International Airport. Deemed as the largest extension in Chinese airport history, the T3 building, a part of the extension project, owed months of wages leading to many days of protests by hundreds of workers in November. One of the videos shows workers who gathered in front of the construction project’s office in darkness. The video narrator kept blaming the bosses for not upholding their responsibilities. The narrator continued said: "This year has been tough. Really tough." Other videos showed workers occupying the office building overnight. Although a handful of workers managed to secure blankets and some even had a sofa to lie on, most workers had to rest on the floor.

Protests against unpaid wage arrears and against abuse of other labour rights has become the last resort for workers, and in some cases, workers find themselves in more straitened situations as they could get arrested and beaten up. In an incident in Huizhou where construction workers went to a shopping mall to demand unpaid wages, around 20 security guards sought to prevent them from approaching the entrance. A video showed a handful of police officers too were present and were helping to prevent workers from entering the mall. Later, the security guards marched forward and pushed the workers away while stepping on a worker who had been lying on the floor. One of the police officers finally stepped in and threatened to use pepper spray if the security guards did not stop. In another incident in Sanya, police officers directly confronted protesting workers. In that incident, construction workers at a dental hospital seeking their wages blocked the building entrance. Police arrived at the scene with shields. A video showed some workers lying on the floor during the night. Police officers handcuffed them and dragged them away.

Manufacturing: worker protests as factory closures and relocation continued amidst slow growth

CLB's Strike Map gathered information about 452 incidents in the manufacturing industry in 2024 – an increase from the previous year (438 cases) – at a time when international companies were eager to diversify their investments despite flat domestic demand. The incidents occurred mainly in the best-performing manufacturing provinces, with Guangdong witnessing a total of 166 incidents, followed by Zhejiang (63) and Jiangsu (39). While boasting of possessing the world’s biggest manufacturing economy, China’s manufacturing industry experienced another frustrating year in 2024.

In December, the purchasing managers’ index stood at 50.1 percent, just above the 50-mark separating growth from contraction, signalling slow growth in the industry. The challenging environment was caused by international firms’ diversification strategies which saw expanded supply chains beyond China, i.e. manufacturing shifting to a third country. Official figures show that foreign investment in fixed assets declined by 10 percent in December. On the other hand, domestic demand remained sluggish as evidenced by the barely increased consumer prices.

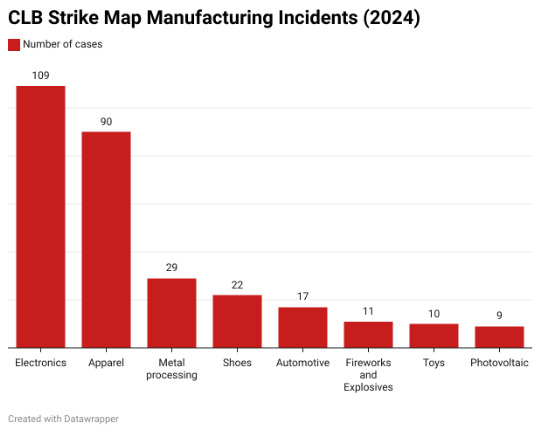

Among the incidents in the manufacturing sector that CLB was able to gather information about, electronics accounted for 109 incidents followed by apparel (90), shoes (22), automotive (17) and photovoltaic (9). As in 2023, the electronics and apparel sectors continued to experience the most protests in 2024. Given the challenges posed by weakened international and domestic demand, some factories were not able to pay their workers and some even closed down.

While companies need to make plans to reduce costs and expand businesses, the rights and livelihood of workers are often absent in the decision-making process. In March, workers at Qiao Feng Technology in Shenzhen, which produces mainly audio and video systems for automobiles, sat in front of the factory gate as the company planned to relocate without offering compensation to the workers.

Photo: A video uploaded by workers from Qiaofeng Technology on 17 March 2024

The protest occurred after workers saw machines being moved from the factory. Although no notice was given to the workers, they sensed that the company planned to relocate the factory. The protest caught the authorities' attention and they intervened in the dispute. Qiao Feng agreed to halt the relocation, albeit temporarily. Seemingly an empowering story, but it did not end well for some of the workers. After the incident, CLB followed up on the development and found that Qiao Feng had dismissed two workers accusing them of “deliberately spreading rumors" at the behest of the enterprise union. CLB enquired with the enterprise union and local federation of trade unions and found that the enterprise union had failed to represent workers adequately as no communication with workers took place over the planned relocation and the ensuing strike.

Foxconn, one of the biggest manufacturers with multiple sites across China, witnessed protests in different locations for various reasons. The world's largest contract electronics maker wanted to cut costs in its Hengyang site and workers saw their subsidies and overtime shifts cut. Workers argued that the practice amounted to redundancy in disguise and went on strike to demand compensation in late May. Another protest occurred over the relocation of the Taiyuan factory to Jincheng. As the distance between the old and new sites meant an extra travel time of more than three hours, management arranged for workers to be transferred to the new site and undergo training. But no discussion around compensation was held. In November, hundreds of workers took to the streets, chanting “Workers! Protect our rights!” and hoping the local union could offer help. Long-time employees said that they were disappointed over the mistreatment by Foxconn.

In the apparel and shoe sectors, workers in smaller factories faced unpaid wages as owners delayed salary payments and became uncontactable later. As factories in some sectors chose to locate in the same area, the changing industry environment led to a significant amount of labour rights-related incidents. For example, the Strike Map recorded 20 incidents in the apparel sectors in Jiaxing alone throughout the year.

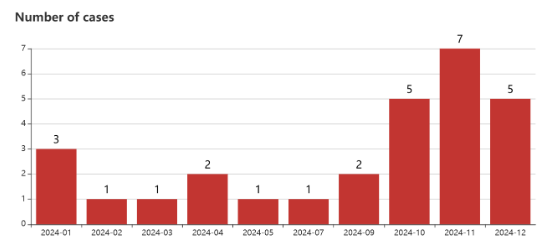

Chart: Number of worker unrest reported in Jiaxing, Zhejiang in 2024

The number of protests peaked in the city from October to December as the city witnessed at least 17 protests. The operational challenge was not exclusive to individual factories but across the sector. One of the biggest incidents occurred in October when workers protested for over a week. An owner of an apparel factory in Puyuan Town, Jiaxing suddenly became uncontactable: he had not settled workers’ salaries. Workers became desperate and one of them even attempted to jump from a building. Workers gathered at the factory and some tried to hunt the owner down. In a video posted later, the owner was seen walking alongside police officers and surrounded by a crowd. The company had to finally fulfil its legal obligation to pay its workers. However, it is unclear whether there was an official intervention and whether the owner was willing to, or able to, settle all of the unpaid wages. In another incident in November, an employer owed 50 workers' wages and offered only 20,000 yuan to them. Reports indicate that workers were owed two months’ wages. Dividing the amount offered by the number of workers, each of them would have gotten a tiny sum of 400 yuan. Netizens commented that the offer could barely cover a day's salary. Labour rights abuse in the apparel sector should also be considered in the context of international demand, as in Nordd Leather's case, according to a CLB report. In May, the Dongguan factory closed down suddenly with workers’ wages and social insurance remaining unsettled. The closure came as multinational brands such as Burberry and Tapestry faced pressure to cut costs.

The leather industry sector also recorded a concentration of workers’ protests in some cities, although they were less severe than in the apparel sector. Wenzhou in Zhejiang province recorded seven incidents, while Quanzhou in Fujian province recorded five incidents in 2024. In an incident in Quanzhou in October, an owner disappeared while the registration of the company was scrapped. With three months of their wages having remained unpaid, workers gathered at the factory and also tried to seek help from local officials. However, a worker who posted videos on social media about the incident commented that neither the labour department nor the police were helpful. Another incident in December saw an owner cutting costs by squeezing workers' hard-earned salaries. The owner kept wages unpaid, and when workers couldn't take it anymore and resigned, he then offered the workers 70% of their wages. The workers concluded that although they would get paid, the amount would not do justice to the labour they had contributed. The international dimension was also in play in the protest against Jinweili Sporting Goods, a manufacturer of Vans shoes, in Leshan. Workers went on strike because of unpaid social insurance.

The photovoltaic and vehicle sectors which have attracted heavy investments, accounted for a low share of labour rights-related incidents in the Strike Map in 2024. China dominates the global solar photovoltaic supply chains and exports saw an 18 percent increase for the first nine months in 2024 compared to the same period in 2023. Although workers' protests in the photovoltaic sector were not as common as those in other sectors, violations of labour rights were reported, leading to massive counteraction as shown, for instance, in CLB’s report on Akcome Technology. Employees were notified on 7th June that the company would stop production the next day until the end of August. Although a living allowance plan was in place, it massively affected workers' livelihood as they were to receive only 70% of the local minimum wage and had to pay for their social insurance, housing provident fund, income tax and dormitory utilities. During that period, workers were expected not to take up temporary work or they would be denied the living allowance. Protests against a furlough also occurred at Inner Mongolia Daquan New Energy. In December, 800 workers protested the unilateral announcement of a plan to furlough workers for an unlimited period of time in Baotou. The company management had verbally promised to pay 1,000 yuan to the workers, an amount much lower than the local minimum wage, according to workers. Lacking enough funds to sustain themselves and their families, the workers would have had to seek alternative employment. They argued that the furlough amounted to layoffs in disguise. Workers protested for 10 days. The furlough, or layoffs in disguise, showed the overexpansion of the photovoltaic sector leading to companies balancing cost and profit by sacrificing workers' livelihoods. Recently, the Chinese government has raised the minimum capital ratio for starting projects from 20% to 30% for photovoltaic manufacturing, in an effort to cool down intensified competition in the manufacturing sector.

The electric vehicle market has also become an investment hotspot and while workers’ protests in the sector were not frequent, they did occur in 2024. China's exports of new energy vehicles (including electric cars and plug-in hybrids) and domestic sales grew 6.7 percent and 40 percent respectively. One of the most significant disputes occurred at Jidu Auto. Founded by the tech giant Baidu and car manufacturer Geely in 2021 when the electric vehicles market began prospering, Jidu specialised in autonomous electric vehicles. Given the intense competition, with consumption not being able to absorb the excessive supply, companies struggled to hold their ground and more than 50 companies, including FAW, BAIC and SAIC, underwent personnel changes in their management last year. The uncertainty affected not just the companies but their workers as well.

Source: Video from a staff meeting during the protest in Shanghai, Jidu headquarters

When Jidu announced its closure in December, workers in Hefei, Wuhan, Beijing and Shanghai protested over unpaid wages and social insurance. The most large-scale protest occurred in Shanghai as workers gathered for a week demanding a fair dismissal plan. Video reports show that workers flocked to Jidu’s office in Shanghai and surrounded the company's senior management. The high-profile collective action attracted media and government attention leading to a deal: Jidu agreed to compensate workers on an "N+1" basis (N represents the number of years employed) and assured them that salaries and social security would be paid. Even with two massive corporations' backups, Jidu could not escape market pressures and finally shut down. In the process, workers were not consulted but had to fight for what they deserved.

The wage arrears issue at the Shanghai Guoli Automotive Leather Decorations shows how workers’ livelihood issues take a back seat when companies make financial decisions. Founded in 1996, the company was well known for its production of leather seats for vehicles. However, it was reported that the business had begun declining since 2019. The company began defaulting on workers’ wages. Hundreds of workers got together and protested by blocking a road in October. While failing to pay salaries, the company sought to encourage more experienced workers to voluntarily leave the company by offering 3-months’ minimum wages. The company said via a social media post that while it could not pay its grassroots workers, people in its offices had all received their wages. Workers thus felt they were being discriminated against by the company's management.

Services: Local government struggled to fund public services, wage arrears seen in traditional and new sectors while e-commerce strengthened and local government struggled to fund public services

Last year, the Strike Map recorded 148 incidents in the services industry. Protests occurred predominantly in Guangdong (29 incidents) and Henan (13) followed by Sichuan (9) and Beijing (8). Three sectors that accounted for the most cases were catering (25.8 percent; 33 incidents), sanitation (24.2 percent; 31 incidents) and retail (14.1% percent; 18 incidents). Large-scale protests staged by hundreds of workers mainly occurred in the sanitation and medical sectors.

In the catering sector, protestors targeted big and small companies including restaurants and hotels, despite the backdrop of the national economy appearing to have improved slightly. The national urban unemployment rate stayed put at 5 percent in November. Nonetheless, the unemployment rates for younger age groups were higher. The unemployment rates for 16-24 years old and 25-29 years old groups, not including the educated ones, were 16.1 percent and 6.7 percent respectively. Youth unemployment and other factors, for example, changes in consumption patterns, bad investment decisions and increased costs might have led to financial burdens for catering businesses. CLB Strike Map recorded workers protesting against pubs, for example, T61 Bar in Chongqing, M+ Bar in Shenzhen and We Bar in Dongguan. A worker who had wages owed by M+ Bar even threatened to jump from a building. In the hotel sector, protests were related to unpaid wages and in some cases hotel closures leading to incidents such as in Fuzhou, Shanghai and Huizhou.

Traditional retailers such as supermarkets continued to struggle as e-commerce kept growing and sales stood still in 2024. Online sales expanded by 7.2 percent from last year: especially online sales of food and clothing increased by 16 percent and 1.5 percent respectively. The changes in consumer habits have long been threatening the operation of traditional retailers as illustrated by the cases of Carrefour and BBK (Better Life Commercial) which closed down in 2023, as was reported in the Strike Map 2023 Analysis. The two companies alone accounted for 15 incidents in the Strike Map. Although the retail sales of consumer goods had slightly improved in 2024, the fact that supermarkets continued closing down represents the challenges that traditional retailers face vis-à-vis online platforms. Sometimes, these business challenges affect workers in the form of unpaid wages and denial of legally protected compensation. In April, Hubei Fudi suddenly closed down its stores leaving the public in shock and workers unemployed. Regarded as the “rural Walmart”, Fudi once had a total of 533 stores and hired more than 10,000 workers. Before the shutdown, workers had already experienced unpaid wages. Two weeks after the closures, a court notice was posted on every store asking people to go to specific locations to register. However, some workers decided to stage a protest in Xiantao to demand that their wages be paid soon.

Source: Photo of the strike of Fudi supermarket employees in Hubei, shared by Yesterday (X Account)

A notice by a local court indicated that Fudi would enter a debt restructuring process and would have to file creditor claims by mid-July. However, wages remained unpaid for months and workers had no choice but to stage a protest again in mid-September. Although officials were aware of the Fudi closures, salaries remained unpaid. The incident illustrates the vulnerability of workers as their rights are often neglected when it comes to businesses’ financial decisions.

When workers lose hope in getting their demands addressed by management and owners, they take recourse to calling for government intervention in order to get their compensation as those at Ganyuting Supermarket did. The 32-year-old brand had 2,000 workers and 67 stores. Its surprising closure in late October left workers high and dry with unpaid wages. Workers gathered outside the local government office in Ji'an in a bid to draw attention to their plight. However, things did not go smoothly as the police who were present played an audio accusing workers of "severely affecting the department's operation". Two workers were held before an official from the local government came out and asked workers to "cooperate". The official said that the office premises were not appropriate for workers to voice their demands. Meanwhile workers clamoured for the release of arrested colleagues. Thus the attempt at seeking government assistance in this case only caused more trauma for workers after they had lost their jobs.

Workers in the sanitation and medical sectors too experienced unpaid wages as public service provisions got restricted thanks to financial pressures faced by local authorities. Although the number of protests in the sanitation sector fell compared to 2023 they were still higher than during the pandemic and pre-pandemic periods. The number of incidents in the medical sector rose by 3 cases from 2023 to 17 cases in 2024. A handful of incidents were related to local governments, signalling the challenging financial pressures they faced.

Source: Video shared on Douyin by a passerby

In mid-December, hundreds of sanitation workers in Xi’an surrounded the government offices and blocked the road as their wages had been unpaid for five months. An official said the government lacked sufficient funds to pay the sanitation company employing the workers and promised that payment would be made by the end of the month. In late December, sanitation workers in Anshan went on strike leaving litter all over the streets as they had not been paid for three months. The town governing body said they needed to wait for the city government to allocate funds. Until then, there was nothing they could do, they said. Earlier, in July, sanitary workers in Ningbo protested the government's decision to cancel the allowance for working in high temperature conditions. Apart from local governments, private companies too witnessed protests by sanitation workers seeking to protect their rights. One significant incident occurred in Dongguan where workers went on strike for almost 20 days in July: It transpired that a new company engaged in sanitation reduced workers’ salaries, according to an online report. The collective action ended with a positive result as the company that had previously handled the project resumed operations and workers returned to their spots. Such incidents underline the fact that sanitation workers too face different forms of labour rights abuses by both private companies and local governments.

Just under half of the incidents (8) in the medical sector were related to wage arrears in public institutions. In all but one of these cases, workers protested because of unpaid wages. For instance, dozens of workers protested outside a public hospital in Xinxiang as they had not been paid for as long as eight months in October. They displayed a banner in front of the entrance, which said: "We need to live." In the same month, workers at a public hospital in Zhengzhou took to collective action after not having received their salaries for many months. A video report showed workers in healthcare uniforms surrounding the car of one of the hospital’s managers. A journalist who contacted a senior officer of the hospital was told the issue was being sorted out and that nothing further could be disclosed at the time. Protests were also seen in private hospitals. Workers at a facility in Xianning demanded wages, the hospital having gone empty after mere four years of operation: some workers had stopped working due to unpaid wages. A social media report said workers had to borrow money to sustain themselves. In December, a maternity hospital announced its closure citing the effect of the pandemic, economic downturn, lower maternity rates and bad management. Although a notice had mentioned a settlement plan for workers, the hospital’s closure left workers in dire straits. Having lost hope after the sudden announcement, workers threatened to jump from the building in order to demand their salaries. In CLB’s extensive report on healthcare workers' rights violations over the past decade, we have been advocating a stronger commitment by unions to truly represent the workers as their rights continue to be abused.

Transport and logistics: Cabbies protest to protect their livelihoods while ride-hailing drivers' earnings also get squeezed

As competition posed by the ride-hailing platforms intensified, taxi drivers staged protests: in the Strike Map of 2024 they accounted for 25 out of 64 incidents. The ride-hailing market has expanded rapidly as a total of 362 platforms had received permits nationwide until October – a surge of 72 platforms (25 percent) in two years' time. Meanwhile, the number of driving permits increased by 2.59 million (53 permits).

Source: Taxi drivers went on strike to protest against car-sharing in Xiangxi, Hunan (Douyin)

Frustration among taxi drivers turned into collective actions to protest the expansion of ride-hailing as seen in, for example, the strike in Xiangxi in April, in Wuhai as well as a petition in Ganzhou.

Given the influx of ride-hailing platforms, taxi drivers faced pressures from their companies and governments that further threatened their livelihood. Some drivers organised and staged protests in which hundreds took part. In March, taxi drivers in Ningbo petitioned the local transport bureau arguing their platforms were charging too much for drivers to transfer their taxi vehicle licenses which could range from 5,000 yuan to 15,000 yuan. However, the official response referred to the transfer of permit as a breach of contract, and the penalty was reduced to 5,000 to 6,000 yuan. In Heze, taxi drivers went on strike in July to demand that local government subsidise fuel. In November, drivers in Nanchong went on strike for four days to protest against the high management fee they needed to pay their company. They criticised the 200-yuan fee, saying it was higher than that in some first and second-tier cities. The collective action prompted the company to reduce the fee to 170 yuan per day.

A strike in Xiangyang in early September prompted the local government to intervene in the interest of drivers. The government had ordered taxi drivers to transfer their permits to a designated company. However many drivers were reluctant to do so, arguing that they had spent the money to buy their vehicles and therefore should own the permits. The government assigned officials to check drivers' permits and one driver was held. After that, hundreds went on strike to show their solidarity and oppose the government's action. As many as 807 drivers resisted the order to transfer permits by suing the local government and transport bureau, a court notice showed. Another large-scale strike occurred in Jixi in November. The local government announced that a fuel surcharge for taxis would be scrapped, which meant that drivers would earn less. Drivers immediately decided to go on strike as they could not accept their income being squeezed.

Unlike taxi drivers who work for particular companies and are able to connect with peers, ride-hailing drivers find it difficult to organise and protest against the platforms they work for. They feel pressured to work harder to make ends meet in this oversaturated sector. In an extreme example of such oversaturation, in a Shanghai airport in September, at a given point of time there were 868 platform drivers present whereas only 39 rides were needed. Facing high competition and low earnings, compounded by steep commission fees to be paid to the platform, some ride-hailing drivers decided not to turn on the air conditioning despite boiling weather. Once offering decent emoluments and flexibility, ride-hailing has become a risky occupation and cities such as Xuzhou, Putian, Suzhou and Xiangtan have issued notices to potential drivers urging them to rethink before joining the sector. The hardship of ride-hailing drivers has been acknowledged: their isolated working conditions and lack of union representation has meant that drivers cannot easily organise to demand changes from their platforms in terms of wages and working conditions. While ride-hailing platform drivers have been struggling, big corporations have been further expanding their services, which could be to the detriment of the drivers. Ride-hailing companies including Didi, T3, and CaoCao have all attempted to invest in autonomous driving taxis (or Robotaxi). The CLB Strike Map has recorded an incident in which ride-hailing drivers protested the introduction of Apollo Go commuter scooters in Hangzhou. The Baidu-backed autonomous service had trials in 11 cities in China. If they were to gain popularity, taxi and ride-hailing drivers’ job security and earnings would face significant threats, potentially leading to widespread disruption in their livelihoods.

In the express delivery sector, the Strike Map recorded 10 incidents in 2024. Although the number of incidents fell compared to previous years, the pressure and workload for express riders would have increased as the number of parcel deliveries reached the national highest. A new law prohibiting riders from putting parcels in an express box or parcel collection point without recipients' agreement also put extra stress on riders given the already massive amount of parcels. The express delivery market was dominated by SF Express and JD Logistics, but other companies including ZTO Express, STO Express, Yunda Express and Deppon Logistics have been trying to gain greater market share. However prosperous the activities were for these companies, workers needed to actively protect their rights. In March, Tangshan witnessed courier drivers’ protest against JD for lowering their wages. They claimed that the highest pay cut amounted to 35%. Four cases related to Yunda Express were recorded in different places. Three of them were regarding unpaid wages in Nanyang, Foshan and Guangzhou. The biggest protest occurred in December when 300 couriers protested against a plan to relocate the distribution centre from Hengyang to Changsha. The two-day protest occurred as the company did not provide compensation to workers while laying them off. Workers also revealed that the company owed them social insurance and bonuses for working on holidays. JD planned to hand the distribution centre to a new owner a few days after the closure without consulting workers: this highlights the absence of workers' voices in the decision-making process. "They don't care whether we are dead or alive," a worker said, complaining about JD.

In the storage sector, workers at a company in Zhaoqing went on strike in March as wages had been unpaid for months. In June, truck drivers in Dongguan blocked the road to protest against charges for parking that had not been imposed previously. In the shipping sector, hundreds of workers went on strike in Jiangmen in August to demand wages that had not been paid for a year.

Heavy Industry: Steel mills workers protest demanding wages and fair settlement compensation

Of the 21 incidents recorded in the heavy industry, most occurred in the steel and metal sector (11 incidents), followed by the chemical sector (5). China recorded the highest steel exports in 2024 since 2015 but total output fell 1.7%. With the trend of urbanisation slowing down, the demand for steel for construction and infrastructure has fallen. The oversupply from steel mills as reflected in falling steel prices means competitive pressure in the sector. Market pressures along with bad management leaves workers in limbo as happened in the case of Xiangfen County XinJinShan Special Steel in Linfen. After being laid off by the steel company in late August, workers protested twice in September (13th and 27th) to demand their wages and a decent compensation plan. After financial scandals such as funds being transferred out from the company, it said it was owing debts and salaries to over 2,000 workers, according to a notice in early September. It did not offer a concrete plan regarding the pending wages and layoff compensation. Instead, it asked workers to wait. Given the uncertainty, workers decided to protest in front of the company entrance to make their voices heard. In an open reply to a complaint in December, the local government said that XinJinShan would pay a total of 12,551 yuan to the complainant by 20th January 2025.

Another significant incident occurred in the Shaanxi Hanzhong Iron & Steel Group Company in Hanzhong where workers protested for weeks seeking government intervention in order to get their wages and social and medical insurance settled. Workers claimed that the company owed them six billion yuan out of which social insurance accounted for almost four billion over the past decade. The protest started as early as in mid-October and lasted until early December. Video reports showed workers gathered outside the government building and spilled onto the road. At the peak of the protest, there were 300-400 workers gathering, according to one of the demonstrators. A video report showed a worker leading others in chanting "we need to eat", illustrating the devastating state that they were in as the company continued to deprive them of their salaries and the authorities' reluctance to intervene. Overall, the incidents in the heavy industry sector were low in 2024. The industry was still a profitable one and employed a large number of workers. However, labour rights abuses in the industry are not to be overlooked.

Conclusion: unions need to represent workers and companies need to be held accountable

The challenging economic environment of 2024, characterized by uncertainties in the real estate market, shifting geopolitical dynamics affecting exports, overproduction in manufacturing, evolving consumer behaviours due to e-commerce, and competition in the ride-hailing and express delivery sectors, has further exacerbated the neglect of workers' rights. As demonstrated by incidents documented in the Strike Map, workers have faced issues such as layoffs, unpaid wages, and lack of social insurance. This underscores the urgent need for both unions and corporations to be held accountable for protecting workers' rights.

First, trade unions must prioritise accountability to workers. CLB’s research highlights that union chairpersons, in many instances, are corporate executives, creating a conflict of interest that prevents unions from truly representing workers. To address this, unions must actively engage with workers to understand their concerns and proactively communicate with enterprises to anticipate workplace changes that may affect workers' rights. CLB has long advocated for unions to reform their structures and practices to genuinely serve as representatives of workers, rather than reacting only after labour rights abuses occur.

Second, multinational corporations must be held accountable for labour rights violations in their supply chains. The enactment of new supply chain due diligence laws, such as Germany’s Supply Chain Due Diligence Act (2023) and the European Union’s Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (2024), provides a framework for greater corporate responsibility. At the United Nations Responsible Business and Human Rights Forum in September 2024, CLB presented its approach, demonstrating how workers in China use social media to share grievances and document labour rights violations, even in the face of internet censorship. This wealth of worker-generated information can hopefully enable companies to conduct due diligence and prevent human rights abuses in their supply chains.

By focusing on these two key directions—ensuring union accountability and utilizing supply chain legislation to hold corporations accountable—CLB envisions a future where workers’ rights are not only protected but also prioritised, where their voices are amplified and heard, and where fairness and dignity define their treatment in the workplace. While we recognise that achieving this vision will be a challenging and complex task, CLB is committed to keep fighting.

Further CLB reading

- China Labour Bulletin Strike Map data analysis: first half of 2024 in review for workers' rights (published on 19 September 2024)

- An introduction to China Labour Bulletin’s Strike Map (last updated January 2024)

- What You Need to Know About Workers in China: Workers’ rights and labour relations (last updated July 2023)

- Breaking the Mould: Germany's Supply Chain Act as a New Approach to Global Labour Rights Accountability (published on 26 August 2024)