For pdf version of the report, please refer to this link

Introduction: From an isolated case to a brand communication

On 27 October 2023, China Labour Bulletin (CLB) spotted an ongoing strike at an automobile parts factory in Shenzhen, triggered by the factory transferring assets to another production site and laying off workers. With no shutdown announcement or compensation plan for relocation, workers gathered at the factory gate to demand an explanation.

In this strike that lasted for nine days, two incidents stood out. First, a statement released by the factory management acknowledged issues of unpaid social insurance and housing funds. But the factory only agreed to repay contributions owed within the last two years, rather than the full amount, which goes against the labour law. Second, videos posted online by workers and preserved by CLB show that workers clashed with an unknown group of thugs after the company had previously set up a “factory brigade” of private security.

CLB decided to contact a German brand associated with the factory. Regarding the alleged beating of workers by the factory brigade, CLB cited one section of the new German Due Diligence Act, which prohibits companies from hiring private security forces in the factory that harm life and limb, or that impair the right of workers to organise or their freedom of association. CLB urged the brand to act in its own best interest, investigate the facts, and ensure that no laws were violated in its supply chain. The company wrote back to CLB, saying that they would investigate the matter. The communication with CLB is still ongoing.

These events prompted CLB to consider the current state of the global supply chain, leading to two main observations:

1) A new wave of supply chain due diligence legislation is being enacted in Europe, changing the landscape for brands’ responsibilities in the region. This law can be utilised for the benefit of China’s workers.

2) The increasing number of strikes in the manufacturing sector underscores the urgent need for new monitoring and intervention strategies from local governments in China, regional suppliers, and international brands.

This report develops naturally from these two main themes. CLB analyses the post-Covid changes in China’s manufacturing industry from a workers’ rights perspective, describes our data collection and case investigation methodology, and introduces how we have begun to interact with stakeholders along the supply chain through this approach. Finally, we provide recommendations for suppliers, brands, and members of civil society to join in our approach, with the goal of collaborating for improved global supply chain practices.

Contents

1. Background: A surge of factory strikes in China and a wave of due diligence legislation in Europe

2. Worker grievances and the necessity to engage stakeholders along the supply chain

2.1. Case Study: Factory relocations and shutdowns leave workers without legally-mandated economic compensation

2.2. Case Study: Workers in the industry face systemic violations including excessive overtime, low pay, and lack of clear labour relations

2.3. Parent and downstream companies need to be engaged through new legal tools

3. CLB’s new approach to labour advocacy along supply chains

3.1. Case I: Factory relocation

3.2. Case II: Death from overwork

3.3. CLB’s research and advocacy methodology

3.4. CLB’s engagement with Stakeholders

4. Conclusion: China’s workers and global supply chains

1. Background: A surge of factory strikes in China and a wave of due diligence legislation in Europe

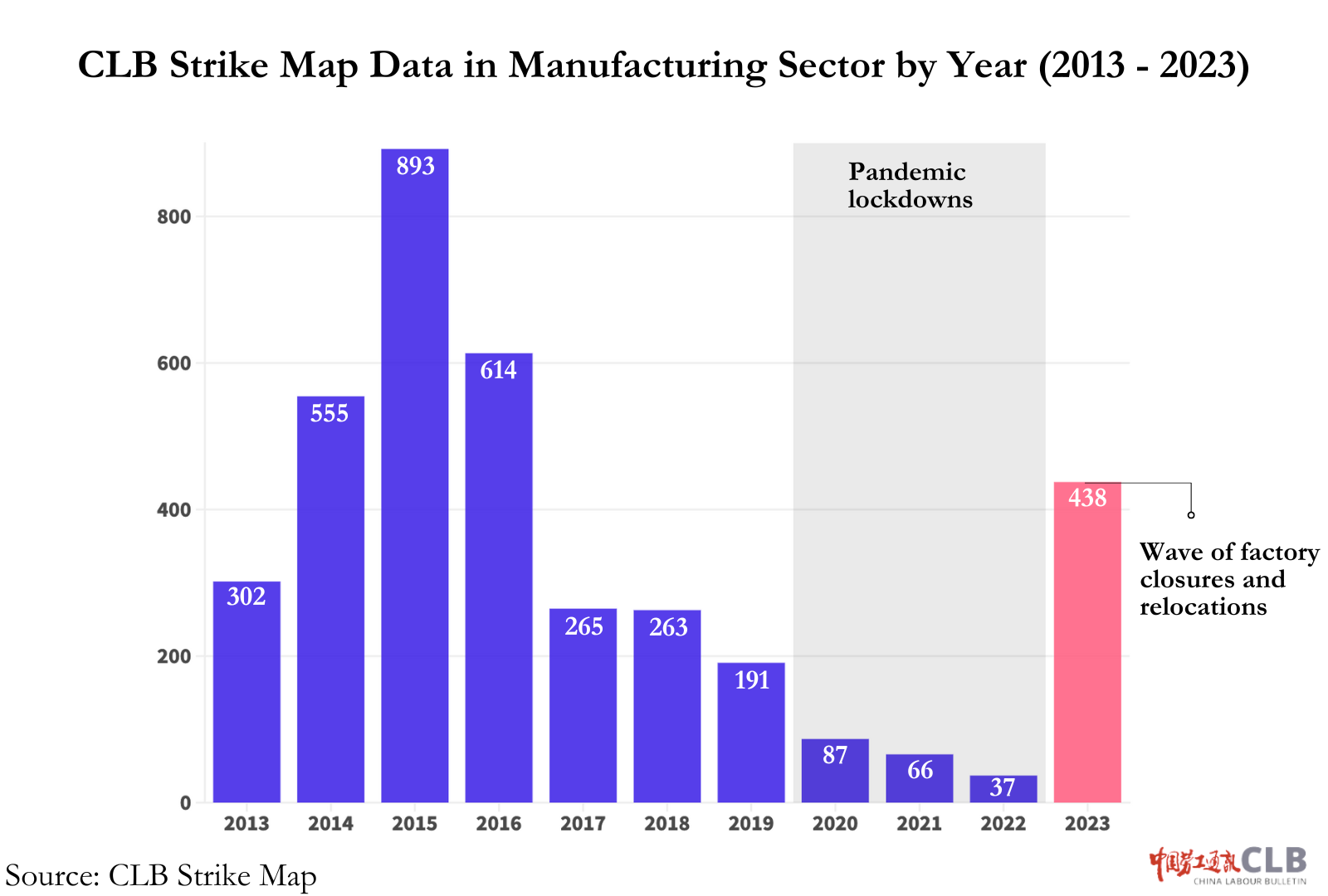

At the same time as the German Due Diligence Law (Act on Corporate Due Diligence Obligations in Supply Chains) came into force in January 2023, the post-pandemic global recession and companies’ shifting business strategies caused a rise in manufacturing protests in China.

Starting in early 2023, workers began posting on domestic social media at a higher rate than in previous years about strikes and protests at factories. Many of these posts were made on the Douyin short video platform, and CLB changed the Strike Map data collection methodology to encompass this source of information through manual searches.

Since 2011, CLB has operated the Strike Map, which has collected over 15,000 strikes, protests, and other collective actions by workers in China. Official data on such incidents is not available, and CLB predicts that our map only collects about 10 percent of all incidents that occur. Still, the patterns of worker voices over time align with broad economic changes and have served as indicators of labour relations trends.

Broadly, after pandemic-related temporary shutdowns, businesses restarted production but at lower intensity. Workers and employers faced a lot of uncertainty in early 2023, as factories faced lower orders from regional suppliers and international brands. Companies began shutting down entirely, consolidating production in existing facilities, or relocating altogether to inland areas where production is cheaper.

The problem became so commonplace that just before China’s annual autumn “Golden Week” holiday period between the Mid-Autumn Festival and Chinese National Day in 2023, factory workers posted online warning each other to beware of factories shutting down without notice during the week off, potentially leaving workers with unpaid wages and benefits and without jobs.

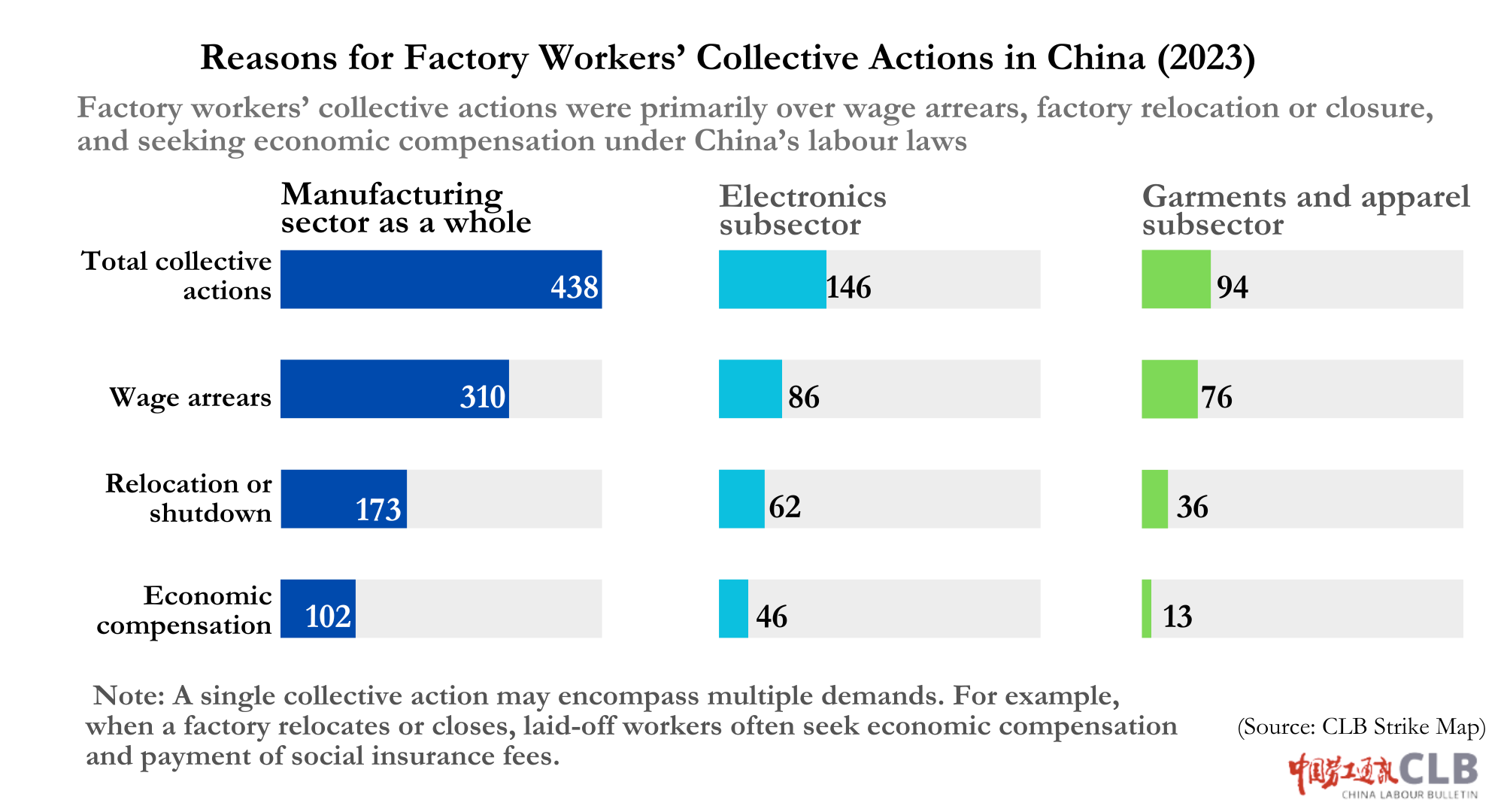

Altogether, workers’ strikes and protests in the manufacturing industry increased tenfold year-on-year, reaching 438 incidents in 2023. This reversed the trend of decreasing manufacturing protests after the wave of factory closures in 2014-2015.

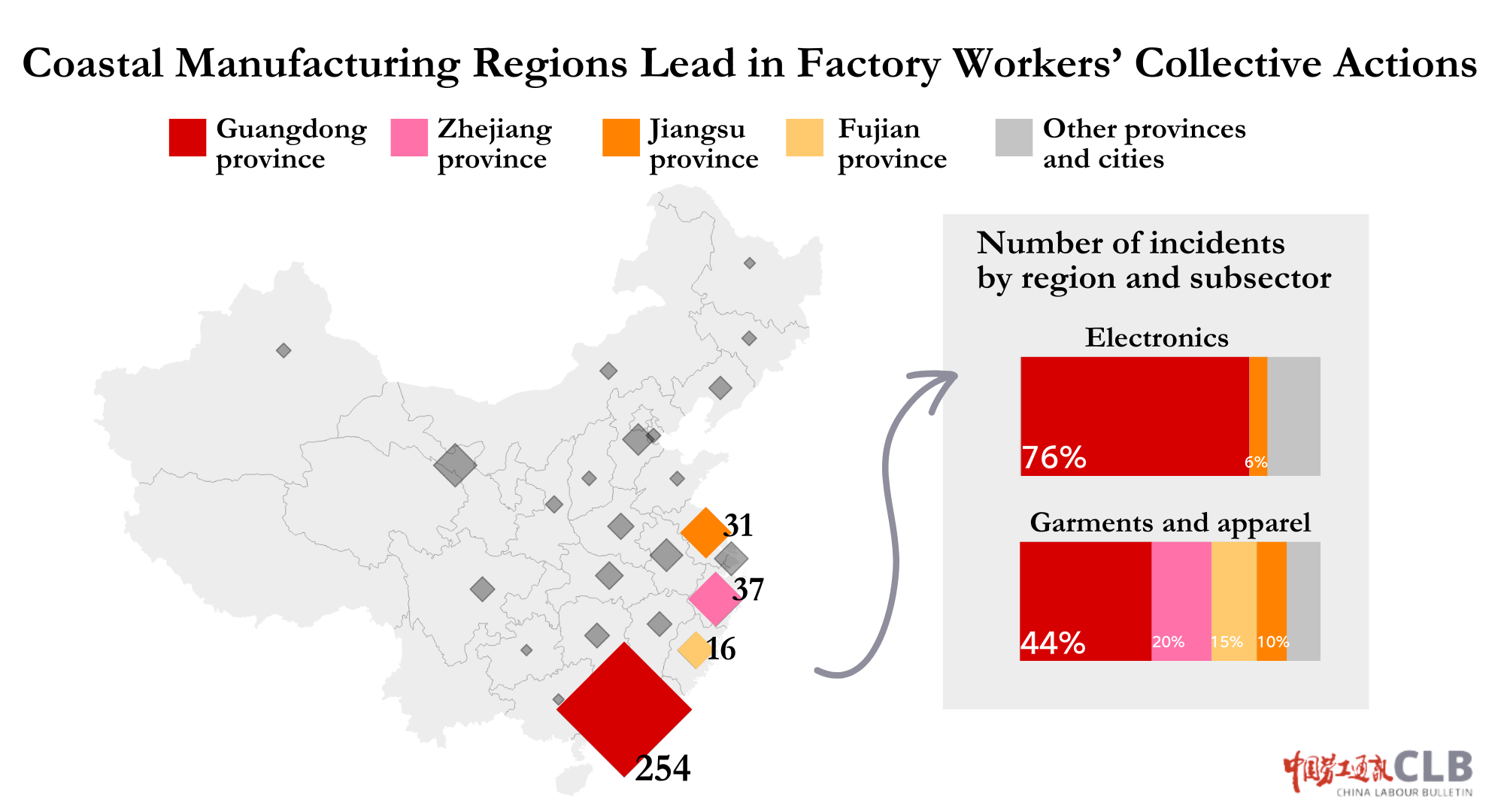

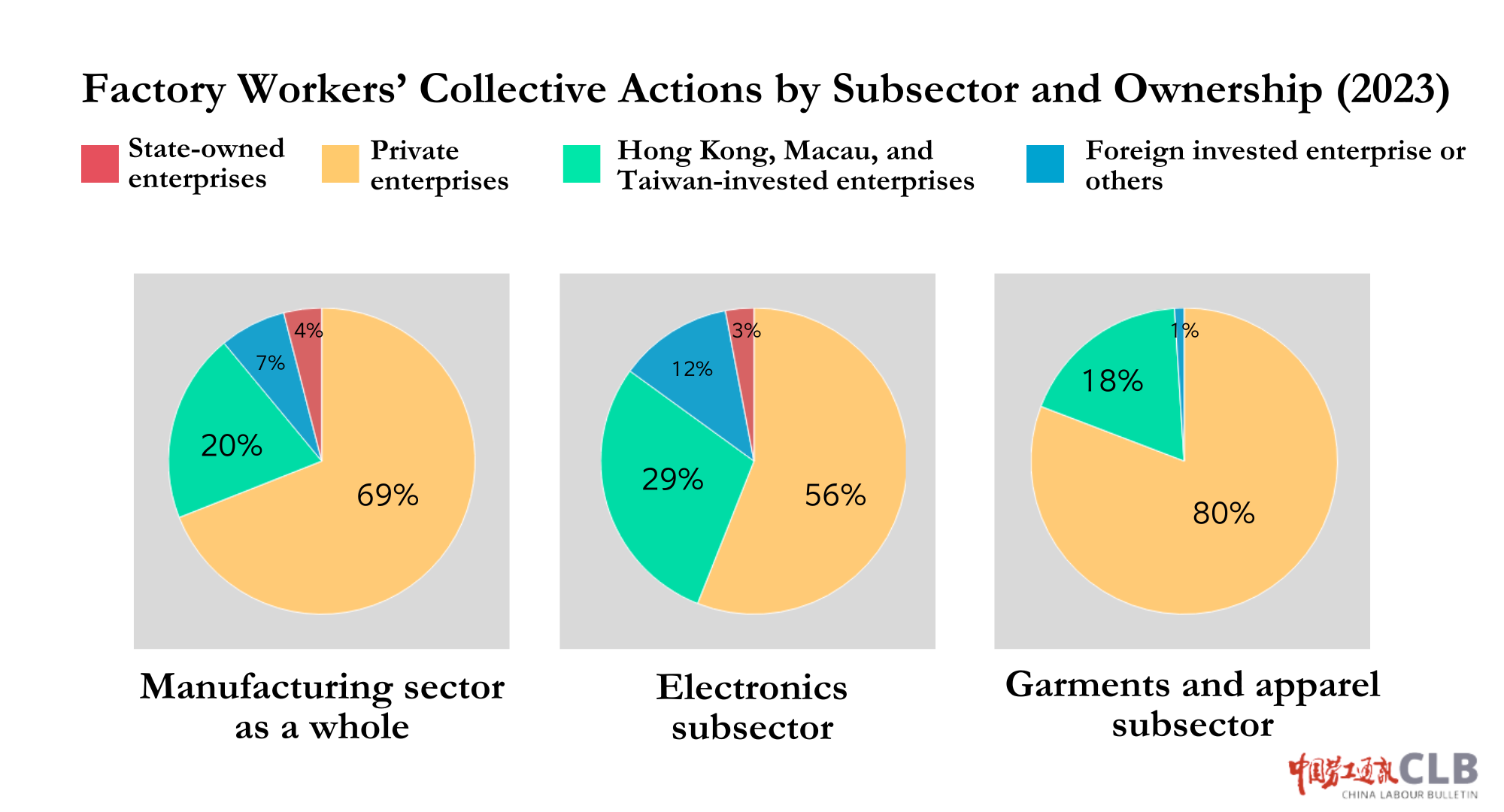

Manufacturing workers’ protests collected by the Strike Map were concentrated in the electronics and apparel industries, with the former accounting for 146 cases (about 33 percent) and the latter accounting for 94 cases (about 21 percent). Wage arrears in failing companies, factory relocation or closure, and layoff compensation were the most frequent grievances of workers’ strikes and protests.

The two industries were particularly hard hit by the economic downturn. According to data from the National Bureau of Statistics, from January to November 2023, the profits of manufacturing enterprises with annual business revenue over 20 million yuan fell by 4.7 percent year-on-year. Among them, electronics manufacturing enterprises’ revenue decreased by 11.2 percent, and for garments and apparel, the decrease was 4.8 percent.

Manufacturing protests were mostly found in coastal provinces, where many export-oriented factories are located. This trend matches the regional distribution of factory workers’ strikes and protests in China. As of 2020, official data shows electronics factories are primarily in Guangdong province, followed by Jiangsu, Shanghai, Jiangxi, Hunan, and Chongqing, while textile, garments, and apparel factories are concentrated in Zhejiang, Jiangxi, and Guangdong provinces.

From the CLB Strike Map, we can also see that workers’ actions are concentrated at domestic private enterprises, followed by those with investments from Hong Kong, Macau, and Taiwan, and then those with foreign investment.

2. Worker grievances and the necessity to engage stakeholders along the supply chain

As China Labour Bulletin (CLB) witnessed the many labour rights grievances and the rise of protests throughout the year, we studied the phenomena from a case-based approach and found patterns in the reasons for worker strikes and protests, often related to patterns of how employers and local governments have handled the changing economic environment.

Workers in China’s manufacturing sector faced a number of pressing rights issues requiring solutions beyond enforcement of domestic laws and implicating a range of stakeholders across the supply chain. This section describes two cases that represent the common issues in China’s manufacturing industry, and the following section describes CLB’s new approach to responding to these issues.

2.1. Case Study: Factory relocations and shutdowns leave workers without legally-mandated economic compensation

In cases of factory closures or relocations, workers were often dismissed on short notice. Factories sometimes did not announce compensation plans, or the plans did not meet the amount required under domestic law. In addition, workers were usually owed wages or social insurance payments and other legally-required benefits. Knowing they had limited time to claim such rights and make companies respond, workers often resorted to strikes to increase their leverage.

The plight of workers at two factories producing electronics components for a U.S. company is illustrative of the longsuffering in the industry coming to a head in 2023.

In late 2022, the U.S. company, which we will refer to simply as Company A, announced the consolidation of nine of its production sites in China, expected to be completed in mid-2023. The factories would be consolidated into “a single centralised site” in another city. However, according to workers’ online posts studied by CLB researchers, many affected workers were unaware of the plan or how it would affect them.

In the first factory (Factory 1) of Company A, workers’ hours were reduced in early 2023 without explanation. Then came a management campaign for workers to “voluntarily” resign in June and July. A worker who signed an agreement in June wrote:

We went to the government for help, but they are not helping. No one is enforcing the law. The labour bureau stands with the factory, even. As migrant workers, we can do nothing but to be treated like this here, where our social insurance policy is not enforced locally.

Workers sought to negotiate with management to learn the company’s plans and their fate. Instead, workers were offered a dilemma: choose between receiving a small amount of economic compensation - only a fraction of what is required by the Labour Contract Law - or receiving unpaid social security benefits. Not only is this offer against the law, but it also reveals how Factory 1 had been violating China’s labour laws for some time by not paying benefits.

Shortly thereafter, workers producing components for another factory (Factory 2) of Company A got wind of the plans for their “voluntary resignations” around the annual Golden Week holiday. Some workers were asked to use their annual leave after the holiday so that the factory would not be in production for fifteen days straight. This was followed by waves of layoffs, starting with workers who had less than seven years of seniority, and then two days later those with less than ten years of seniority were laid off.

In the end, workers at Factory 2 were reportedly given their legally-mandated economic compensation. However, that calculation was based on the average wage of the previous twelve months. Because of the reduced hours related to the industry’s downturn, workers’ average wage was less than half of what they had made for the better part of their careers.

The situation of workers in China producing for U.S. Company A highlights how certain employers try to circumvent labour laws to avoid fully compensating employees during layoffs. Employees were pressured into resigning voluntarily or accepting reduced compensation packages. Without collective action from workers, it is unlikely that the relevant labour laws would have been strictly followed.

2.2. Case Study: Workers in the industry face systemic violations including excessive overtime, low pay, and lack of clear labour relations

Of course, not all factories in China are shutting down or relocating. Workers in the industry face ongoing labour rights challenges on the factory floor. One systemic problem is that workers endure long hours and lack of rest. It is common for electronics factory workers to have 12-hour shifts and work six days per week.

Workers’ wages consist of a base salary plus overtime pay. The base salary usually only meets the local minimum wage, which in 2009 only covered around 40 percent of the living wage and has not meaningfully risen since then. Analysis by the Initium indicates that with slower growth in the minimum wage since 2010, it now covers even less of the living wage or average wage. Consequently, workers heavily rely on overtime pay, often at the expense of their health.

In August 2023, a factory worker in his early 20s died in his dormitory after working 12-hour night shifts at an electronics factory in Jiangsu province for almost two weeks consecutively. The electronics factory is a subsidiary of what we will call Company B, a Taiwanese company that produces LCD monitors and projectors for international brands.

Based on the young worker’s schedule, the factory of Company B has violated the Labour Law’s basic provisions on a 40-hour work week (Art. 36) plus a maximum of 36 hours of overtime per month (Art. 41).

Overtime and low base pay are closely related. According to a recruitment advertisement of the factory, the base salary of a general worker is 2,540 yuan per month. (The minimum wage in the region is 2,280 yuan, and the average wage is around 3,870 yuan.) With this level of pay, workers are pushed to work overtime to get their target monthly pay of over 5,000 yuan. The factory recruitment advertisement also states that workers rotate on two shifts, and they work six days a week.

The case of the young worker’s death also shows the problem of labour dispatch in China’s factories. According to China’s Labour Contract Law, labour dispatch should only be used for legitimate needs such as temporary, auxiliary, and substitute jobs (Art. 66), rather than for regular hiring. The Provisional Regulations on Labour Dispatch in China stipulate that dispatch workers should not exceed 10 percent of the total labour force (Art. 4).

However, labour dispatch is often used beyond these auxiliary purposes. According to Company's B 2022 ESG report, the factory has 4,761 directly recruited employees and 4,507 non-employee workers. If non-employee workers refers to dispatch workers, it is possible that the factory has more than 10 percent of its workforce hired under labour dispatch arrangements.

In the young worker’s case, the dispatch labour relationship complicated the question of whether his family was entitled to workplace accident compensation. His contract was with an intermediary to work for the factory for a term of two years, which is a long time for a temporary or auxiliary need.

His family requested 1.5 million yuan (U.S. $205,000) in compensation for his death as a workplace injury. But the factory called the death an “accident” unrelated to work, and raised that any liability should be placed on the labour dispatch agency and not the workplace. However, under the Labour Contract Law, the dispatch agency and the workplace have joint and several liability for violations of the law (Art. 92).

The two case studies above highlight a significant gap between China’s labour laws as written and their implementation. Whether facing systemic conditions that affect workers and their families, or acute violations such as during a relocation or shut down, workers need better solutions to upholding their rights. Workers often resort to seeking help from the government, reaching out to local media, or even staging protests to ensure that the laws are upheld. It is in this context that China Labour Bulletin strives to equip China’s workers with additional resources and support.

2.3. Parent and downstream companies need to be engaged through new legal tools

When workers strike or seek media attention to receive their minimum legal guarantees, they are not always successful despite the law being on their side. Although the factories’ lack of commitment and the official unions’ inadequate intervention account for some of the reasons, parent companies and downstream brands also have their role in ensuring and enhancing labour rights in factories. This is especially true when factories are out of funds pending closure, or cannot afford to pay workers a higher hourly wage, due to low profit margins.

Many companies and multinational brands have long made corporate social responsibility (CSR) guarantees and applied for relevant certifications which signal that some minimum standards have been met. Many electronics multinationals have joined the Responsible Business Alliance, for example, and its relevant guarantees and code of conduct can be used to request companies to respond to and remedy labour violations along their supply chains.

Further, a new wave of supply chain due diligence legislation is being implemented in Europe. The German Due Diligence Act came into force in January 2023, and the French Duty of Vigilance Law has been effective since 2017. The European Commission has just approved the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive in February 2024, which will go to the European Parliament for approval.

In this new regulatory environment, brands and companies can be pressed to follow through on their commitments before the legal consequences in their home country are enforced. CLB has been working to understand how such tools can be used to support factory workers’ rights in China and the region. First, we have needed to make changes in our data collection and research methodology to support the use of foreign legislation and other tools. As part of this process, we have also begun to reach out to corporate actors, regional and global mechanisms, and like-minded partners. We share our process and methodology below.

3. CLB’s new approach to labour advocacy along supply chains

CLB’s database is one tool to collect information about labour incidents in China and on which to base supplementary research. In 2023, CLB explored how to better use our data to research specific incidents, find labour rights challenges or violations, and raise these to stakeholders with the power to improve conditions for workers or make wrongs right.

The CLB database has its limitations, and our supplementary desk research likewise cannot fill all the gaps or answer all our questions. Often, CLB will conduct interviews with local trade unions and government officials to confirm the existence of cases. This method avoids putting workers at risk and also can spur the union of local officials to take steps to help the workers, as the system was designed.

Moreover, with new and stronger due diligence tools in foreign jurisdictions being enacted and implemented at the same time as China’s manufacturing sector is facing unprecedented labour rights challenges, CLB took the opportunity to test a new strategy. In the following sections, CLB’s strategy is illustrated with two cases as examples.

3.1. Case I: Factory relocation

In the electronics factory relocation case mentioned in the introduction, CLB learned about workers’ grievances and their strike through Douyin videos. In October 2023, upon the factory’s (referred as Factory C hereafter) moving some production equipment, workers feared that the factory was going to relocate without proper announcement and layoff compensation. Workers united to voice their discontent against the factory management’s handling, and numerous videos of the strike scenes were uploaded to Douyin immediately.

Douyin is a popular short-video platform, and workers use it to share their daily lives and contact each other. During the strike at Factory C, it was used as a tool to share the injustices happening in the factory, and the relevant posts were filled with workers’ comments. Workers at other factories also left suggestions on how to carry out a strike.

Once CLB staff spotted the strike, we began to collect the video clips uploaded publicly by workers. These videos included images of management’s responses to the strike, including official notices, statements, and announcements. The Douyin algorithm also kept CLB researchers updated, as the platform fed new and relevant videos.

Some videos posted by workers at Factory C suggested disturbing events. For example, one video uploaded in early November shows a large number of thugs in green T-shirts entering the factory and attempting to push away striking women workers. In the video, workers shouted: "Hold hands! Hold hands!" A worker shouted: "(They are) beating people! (They are) beating people!" Although the video itself does not show any beatings, the intensity of the scene is worrying.

Based on the videos and workers’ storytelling, CLB started to investigate and tried to answer the following questions:

1. Is there additional evidence to support workers' claims in the videos?

2. Is that sufficient evidence that this factory has violated China’s domestic laws?

3. Is this factory connected with a brand or parent company that is obliged to obey not only China’s domestic laws but also any supply chain due diligence legislation or agreements in effect outside of China?

From management’s own announcements, we were able to determine that Factory C did try to remove equipment without giving any explanation to workers, raising suspicions that the factory might soon relocate or shut down. The factory also acknowledged that it had “historical social security nonpayment issues,” which means that Factory C admitted to failing to pay mandatory contributions for its employees, thus violating China’s labour laws.

In addition, Factory C’s website states that it produces for well-known companies, including a German auto brand. We found that the brand has to comply with the German Due Diligence Act and has created an internal position of a human rights officer to respond to relevant concerns.

With such information and evidence, CLB tried to involve more stakeholders. We found that the local labour bureaus and federation of trade unions went to Factory C after the strike broke out. However, workers said online that they were not represented by trade unions in their negotiation with management. Workers said they were left to fight alone and could not hold out for very long.

After workers gave up the strike, and the local union failed to support workers, CLB tried to seek intervention by utilising the supply chain due diligence legislation. In November 2023, we wrote to the German brand’s human rights officer. We listed the potential labour violations at Factory C and asked the brand to investigate and remedy, as this was in its best interest.

First, we suggested that the brand could find out if there was an enterprise union at Factory C. If so, and if the representatives were not fairly elected by workers, this might have violated China’s Trade Union Law and section 2 (6) of the German Due Diligence Act, which requires companies to respect the freedom of association.

Second, the “factory protection brigade” set up by the management might have suppressed workers’ freedom of association and even damaged workers’ life and limb. This may violate section 2 (11) of the German Due Diligence Act.

Third, as Factory C admitted to not paying social security, CLB suggested the German brand investigate the duration and scope of the nonpayment and rectify the problem.

The brand’s human rights officer quickly responded to CLB the following day, saying they had opened a case file for Factory C upon receiving CLB’s information. A week later, the company sent CLB a second letter, agreeing that the German Due Diligence Act had potentially been violated.

This case is encouraging in that dialogues with brands using the recent German Due Diligence Act may be able to address issues in China’s factories, and this strategy is a path worth pursuing. We anticipate that China’s workers will become more aware of these laws and tools. The official union and workers' representatives may be able to use it as leverage, and brand compliance may benefit employers in China as well. Therefore, in cases of violations in China’s factories involving German parent companies, brands, or other covered entities, workers' representatives could use this law to engage with stakeholders. This process could lead to investigations and negotiations for the better protection of workers’ rights under domestic and foreign laws.

3.2. Case II: Death from overwork

As for the worker death case at the Jiangsu factory of Company B mentioned previously, CLB also tried to involve multiple stakeholders to address legal violations of labour rights to work toward long-term changes.

CLB identified two potential legal violations in the case. First, based on the worker’s schedule of almost two weeks of consecutive night shifts, Company B likely violated the Labour Law’s basic provisions for a 40-hour work week (Art. 36) plus a maximum of 36 hours overtime per month (Art. 41). Second, as the worker was hired through an agency as a dispatch worker for a term of two years and constantly worked overtime, the company might have violated China’s Provisional Regulations on Labour Dispatch, which stipulate that dispatch workers should only be used for legitimate needs such as temporary, auxiliary, and substitute jobs (Art. 66), rather than for regular hiring.

Company B is a listed Taiwanese company with a reputation for sustainable corporate development. It undertakes to follow the Code of Conduct of the Responsible Business Alliance, and it issues sustainability reports every year. Based on these strong frameworks, we hoped that Company B can amend the wrongdoing at the Jiangsu factory systematically and avoid further tragedy from happening again.

In a letter sent to Company B, CLB focused on the overtime issue in the Suzhou factory. We suggested the company implement new policies to address risks to human rights, which include employing more workers to ensure the implementation of the standard eight-hour workday. CLB also raised the related issue of increasing workers’ basic pay, so as to reduce the pressure to work overtime and help promote decent labour conditions.

Our interviews with the local street-level union also revealed that there was no genuine enterprise union at the Jiangsu factory:

I was at the scene of the negotiation [with the deceased worker’s family]. Then we looked into our internal system and found no record of an enterprise union at the factory. The company probably created one when there was a campaign to establish a lot of unions years ago, but it is one that is not functioning normally. We cannot find it in our system now. Therefore, we did not participate in their subsequent negotiation and mediation process

In response to the malfunctioning of the enterprise union, CLB pointed out in the letter that it is important to re-establish the enterprise union at the factory to promote better communication between workers and management, especially on issues such as working hours and workplace safety.

We found that Company B was open to discussions with us. The company replied to our request to investigate in good faith. Our communication with Company B generated more momentum; civil society organisations learned about the case through both CLB’s own report and online articles written by media outlets in Taiwan who picked up CLB’s report. Civil society actors used their own leverage to intervene through their own channels.

In the meantime, CLB shared our findings with the local union in Jiangsu and the higher levels of the ACFTU. We suggested that the trade union could take over the case and help transform the enterprise union at the factory into a genuine union that represents workers.

CLB believes that the intervention can go beyond the fight for more compensation for the deceased worker’s family. By highlighting the labour violations and adverse effects of long working hours in electronics factories, the case can serve as a starting point for bringing systematic change to the problems of overtime work, low basic pay, excessive use of dispatch labour, and malfunctioning trade unions.

Also, by continuously involving international brands and local unions, CLB aims to foster the effective functioning of the enterprise union, which will help monitor the labour conditions and possible violations in factories.

Communications between Company B and CLB are still ongoing, and the company has conducted their internal investigations and is in the process of improving labour conditions in their factories. The results will be shared once the reviews conclude. This case demonstrates that there is room to improve workers’ situations through good-faith communication, rather than shaming brands.

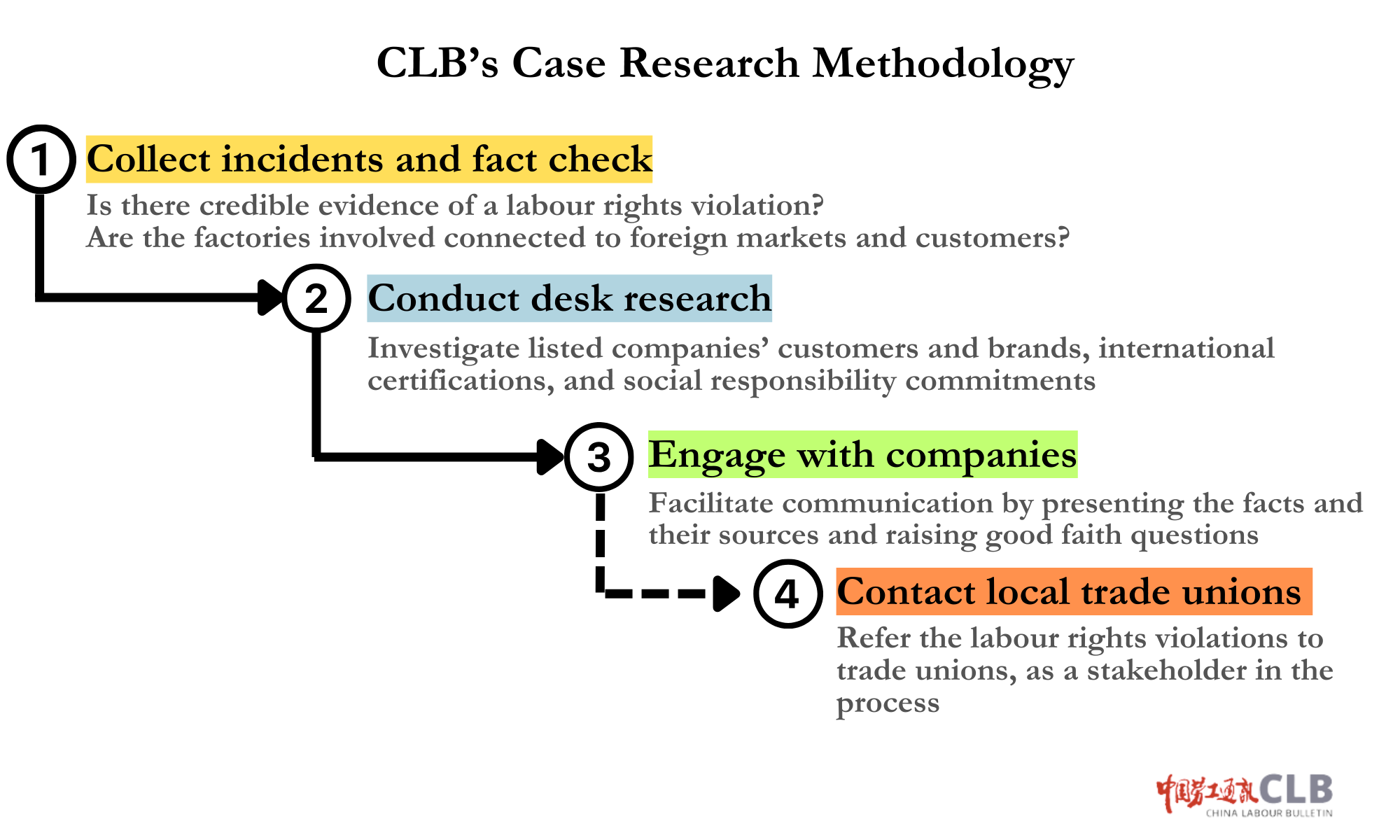

3.3. CLB’s research and advocacy methodology

Workers’ active presence on domestic social media platforms means there is a wealth of labour rights information to sort through. By searching keywords such as “strike” or “wage arrears,” CLB can narrow in on posts by workers defending their rights.

When CLB’s data collectors see an incident, they look for the date, location, industry and company involved, and workers’ demands. If all the information above can be found, the incident is added to the Strike Map, Accident Map, or Workers’ Calls-for-Help Map.

After an incident has been added to CLB’s map database, data collectors may flag particular incidents for the CLB team to further review. Selecting a case that is suitable for this manufacturing sector project has some basic requirements that must be met, and some discretionary factors that come into play.

First, CLB’s researchers look for evidence in the workers’ posts that a workplace has violated China’s labour laws. For example, management decisions may not be clearly explained to workers, leading to rumours or misunderstandings. Relying solely on workers’ conjecture may not be enough to confirm a case to the level necessary to start further research and bring the case to relevant stakeholders.

However, sometimes workers post online photos of their workplaces’ official notices or video recordings of management representatives’ speeches. The content of the factory’s statements often admits some violation of the law and can become important evidence to support workers’ claims. Other documents posted online by workers—such as their payslips, time records, and resignation forms—also support the statements workers write accompanying their videos.

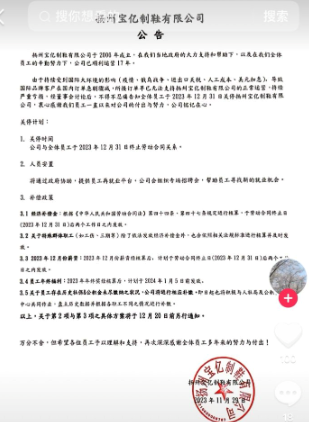

An announcement from factory management during a factory closure, posted by workers on Douyin

Second, after finding credible evidence of a violation, CLB will conduct desk research to learn more about the enterprise and its supply chain. Generally, the larger the enterprise and the more connected it is to foreign markets and customers, the more information is available. Listed companies provide annual reports that often include major customers and brands, international certifications, and social responsibility commitments. Some companies, in order to attract customers, provide information on their websites about their factories, products, and their supply chains. CLB also cooperates with like-minded organisations to check brand relationships through supply chain databases and trade databases, such as Open Supply Hub.

But, as a CLB researcher put it, sometimes the information just isn’t there:

In the worker's industry, it may be impossible to determine, based on existing data, who the products they produce are supplied to or whether the factory is a member of a certain supply chain.

If CLB can confirm that a violation likely occurred at a factory with known brand relationships, then we look for other factors that may make a strong case for this project: “Some typical cases with a macro perspective can raise some big-picture issues and promote the improvement of workers' rights,” a CLB researcher explained.

Once a case is selected for further study, members of CLB’s various teams step in. Some team members are responsible for contacting different levels of China’s official trade union and government departments, making unannounced phone calls, and learning whether there has been an official response to the workers’ incidents.

Other team members conduct additional research on the workers’ online posts, spending hours reading comments, visiting workers’ profiles, and connecting the dots between various workers’ accounts of the same incident. Still others conduct corporate and economic research to understand how workers’ rights were affected by broader forces, and what stakeholders can be called on to engage in the matter.

CLB researchers pay special attention to the concrete evidence on labour violations in a case, as well as the supply chain connections of factories. Flagging social responsibility promises in corporate annual reports, identifying internal guidelines set up by business organisations such as the Responsible Business Alliance, and finding relevant social accountability certificates companies received are the main areas of our research. This information serves as the basis to engage with stakeholders and as material for articles that may receive public attention.

3.4. CLB’s engagement with stakeholders

CLB’s engagement with supply chain stakeholders begins almost as soon as the case is identified, and it often happens simultaneously with the research and writing process.

CLB occupies a unique position relative to the workers, official actors, and corporate stakeholders in these cases. Unlike an independent trade union, CLB is not authorised to represent workers or negotiate on their behalf with enterprises; workers likely do not know that CLB exists or is paying attention to their case. However, CLB also recognizes that we can be a participant through our unique third-party position and urges for dialogue and negotiation on each matter.

When we interact with companies and official entities, we act in good faith and with clear evidence. CLB does not presuppose that stakeholders have deliberately broken laws or treated workers maliciously. Our aim is for the companies to start with the facts and inquiries CLB has raised to conduct their own investigations and verify for themselves whether violations have occurred and whether redress should be made.

We recognize that our information about each case is incomplete and may even be inaccurate - although it is compiled and understood to the best of our knowledge and based on our decades of experience in this field. Therefore, when we contact stakeholders by letter or by phone, we focus on facilitating communication, presenting the facts and their sources, and raising honest and good faith questions that the stakeholder may be under an obligation to look into to protect their own interests.

When we interact with official entities in China, we also politely seek information and even make recommendations for how workers’ interests could be represented. Sometimes the officials hang up the phone on us, but more often than not, they will spend time listening and answering our questions to varying degrees.

We also have the ability to contact like-minded NGOs in other regions who have relationships with brands, official actors, and others who can apply pressure for a better outcome for workers and in line with corporate responsibilities.

The role of foreign legislation on supply chain actors is key to our approach. CLB recognises that the problems in the sector negatively affecting workers’ rights are broader than the worker-employer relationship, are not the sole responsibility of local governments to enforce, and indeed are a global responsibility. Even if China’s domestic laws are strong enough to protect workers in China, employers are under financial strain and simply may not have the funds to pay legal compensation. Regional suppliers and global brands have legal obligations to ensure domestic law is followed, and they have made further commitments according to their relative positions in the supply chain. They should bear some of the responsibility for the disruptions and systemic problems in the sector, rather than this falling on workers alone.

The building of global pressure on corporations is the result of years of advocacy for binding business and human rights instruments, corporate due diligence legislation, and other mechanisms to hold businesses accountable. CLB is surely not the only organisation to follow these changes, but we believe that through our interactions with various stakeholders in the global supply chain as well as utilising the new legislation, we can gradually develop a new way for unions in China and the Global South to enrich their strategies in protecting labour rights. In the end, we want to see unions taking up these new tools and strategies to push for improvement of workers’ rights.

4. Conclusion: China’s workers and global supply chains

This report focuses on the events in China’s manufacturing sector in 2023 and how CLB has responded as an organisation. As more supply chain due diligence legislation and tools are implemented and enforced in the coming years, and as changes in the sector continue to affect the region, workers will need ongoing support for their struggles. Moreover, as the rise of the green economy and advocacy toward a just transition will demand deeper changes to existing practices, workers will face a range of new challenges as their interests are likely to be disregarded by more powerful stakeholders.

Multinational companies are responsible for upholding domestic laws where they operate, and to uphold international laws that protect a range of fundamental rights. Further, home country legislation binds corporations and extends to their activities abroad. Through these kinds of tools, CLB can hope for a better and more responsive supply chain environment that prioritises workers’ rights and foresees the impacts of changes in the sector.

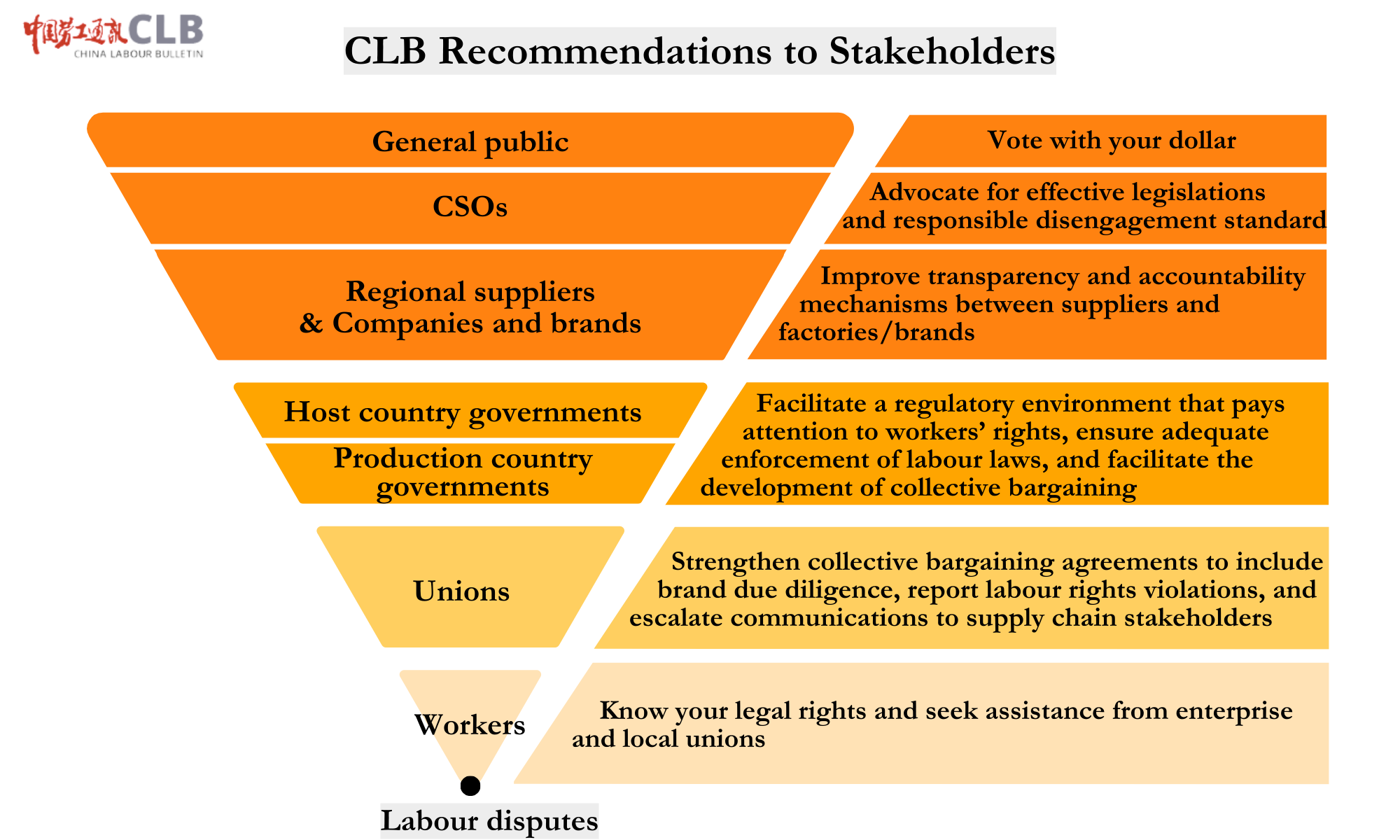

A global approach to workers rights along the supply chain is our vision, and we offer the following recommendations to actors and stakeholders.

1. Workers and their unions:

In China, the ACFTU should facilitate establishment of enterprise unions, understand the needs and concerns of workers, and actively negotiate with enterprises.

For unions in the region, strengthen collective bargaining agreements to include brand responsibilities and due diligence, document and report labour rights violations and escalate communications to supply chain stakeholders when needed.

2. Governments where factories are located:

Not only should local governments facilitate a regulatory environment that pays attention to workers’ rights and labour relations, they should also refrain from suppressing workers’ protests and strikes. Instead, they should facilitate the development of collective bargaining at workplaces, which will be conducive to improvements in workers’ benefits.

3. Regional suppliers:

Establish online communication methods for reporting suspected rights violations or concerns; improve transparency and accountability mechanisms between suppliers and factories, and between suppliers and brands; and implement responsible disengagement policies that involve factories and brands.

4. Companies and brands:

Formulate responsible disengagement policies that account for the high likelihood of workers rights violations in the current domestic and regional environments, engage with suppliers as intermediaries to ensure domestic law are complied with at the factory level, ensure freedom of association across the supply chain and facilitate the establishment of enterprise unions at workplaces in China according to the Trade Union Law, and incorporate diverse sources of information into due diligence and quality control processes.

5. CSOs:

Continue to share information and collaborate with like-minded organisations toward improving workers’ rights along supply chains, continue to advocate for more effective legislation in multiple jurisdictions with strong legal ramifications for evidence-based violations in supply chains, and advocate for specific responsible disengagement standards that respond to the current economic and political situations of various countries in the region.

6. The general public:

Increase awareness of general labour conditions in consumer goods supply chains and avoid overconsumption of products that inherently exploit workers (“vote with your dollar”). Support brands that are more sustainable and promote fairer labour practices in their supply chains, communicate with brands and companies about your preferences for goods produced under fairer labour conditions.