In 2018, there was one labour dispute that stood out more than any other; the campaign by workers at Jasic Technology in Shenzhen to set up a factory trade union.

The Jasic dispute was, at its outset, fairly typical of the thousands of collective labour protests that occurred across the whole of China last year; workers complained of low pay, underpayment of social insurance and an abusive management regime. What made the case noteworthy however was that instead of just focusing on the short-term resolution of these specific economic grievances, the Jasic workers understood that the only way to ensure the long-term improvement in pay and working conditions at the factory was through strong trade union representation. And it was this crucial development that led to the broad support movement that united student groups and Maoist organizations across China.

The vast majority of collective labour disputes in China last year, like Jasic, occurred at domestically-owned private enterprises with no trade union or a union that was beholden to management. These disputes resulted primarily from the gross imbalance of power in labour relations that allowed employers to delay payment of wages and social insurance contributions, refuse to pay lay-off or relocation compensation, arbitrarily reduce pay and benefits, and dictate working conditions.

Of the 1,701 incidents recorded on China Labour Bulletin’s Strike Map in 2018, 1,246 (73.3 percent) occurred in domestic private enterprises, 11.6 percent in state-owned enterprises, and just 2.9 percent in Hong Kong/Macau/Taiwan/foreign-funded enterprises and joint-ventures. Evidence enough that labour unrest in China is very much a domestic problem, and one that can only be addressed with a strong domestic trade union.

Most of last year’s worker protests were small-scale and short-lived; the vast majority involved less than 100 participants and lasted just a few days. Although small in scale, last year’s worker protests were frequent and widespread, covering every province and region of China except Tibet. There were three main centres of worker activism; the economically advanced and populous provinces of Guangdong, Henan, and Jiangsu, but generally there was a much more even distribution of protests across the country than five years ago when labour disputes were concentrated in the manufacturing centres of coastal China and in Guangdong in particular.

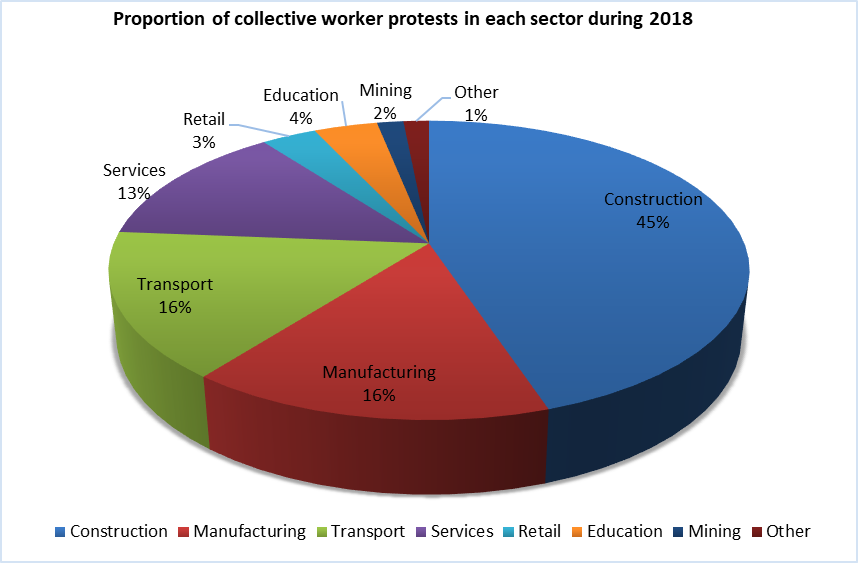

The proportion of strikes and protests in the manufacturing sector has declined steadily over the last five years from 41 percent of all incidents recorded on the Strike Map in 2014 to just 16 percent in 2018 (see chart below). About 19 percent of the factory worker protests were related to closures or relocations, and that proportion is expected to increase as the economy slows and the manufacturing sector contracts. The non-payment of wages was a component in 80 percent of the incidents, again reflecting the precarious state of manufacturing in China and the lax enforcement of labour law. And 17 percent of protests concerned the non-payment or under-payment of social insurance contributions, a problem so severe the government has vowed to deduct contributions directly through the taxation system from 1 January this year.

By far the greatest number of worker protests was in the construction sector, which accounted for 45 percent of all the incidents recorded on the Strike Map in 2018. The consistently high proportion of construction worker protests over the last few years reflects the deeply ingrained systemic problems in the industry that result in workers not being paid for months, even years on end. A staggering 98 percent of all construction worker protests last year were related to wage arrears. And the situation might deteriorate further as the recent slowdown in property sales means there is even less money in the system to pay workers. One noteworthy trend last year was the increase in the number of wage arrears cases related to the collapse of interior design companies, many of which had expanded rapidly before imploding dramatically last May. Interior design companies accounted for about eight percent of all construction worker protests in 2018. Another significant development last year was the nationwide strike at the end April by crane operators demanding better pay and conditions.

Some of the most influential strikes and protests last year were in the transport sector. Truck and van drivers, traditional taxi and ride-hailing cab drivers, couriers and food delivery workers all staged protests over declining income, unfair competition, and arbitrary changes to their pay and working conditions. One of the largest, and best coordinated protests occurred on 10 June when tens of thousands of truck drivers across the country refused to work in protest at low haulage rates, high fuel costs and arbitrary fines. One of the most common complaints last year was the abusive management practices of the internet companies that now dominate the transport industry. Internet platforms, fighting for market dominance, fix prices without ever consulting drivers, while drivers, who rely on these platforms for business, are left to cover rising fuel, maintenance and insurance costs.

The service and retail industries together accounted for about 16 percent of all protests last year, about the same as the transport sector. Protests occurred across a wide range of service industries and were again primarily related to wage arrears, often stemming from business failures. The highly competitive retail sector was particularly volatile and led to 56 incidents involving department stores, supermarkets, real estate agents etc. There were 33 protests by restaurant workers, 24 involving hotel staff, and 18 protests by sanitation workers.

Teachers and education workers in China once again punched above their weight in terms of collective action. The education profession makes up 2.5 percent of the total workforce in China but accounted for four percent of the protests on the Strike Map last year. Some of the most active and best organized protesters were retired community teachers from rural districts who were fighting a long-running battle for decent pensions and other benefits: there were at least nine protests by community teachers in December alone.

As noted above, the one common denominator in nearly all of these protests by teachers, shop workers, truck drivers, construction and factory workers, is the absence of a strong trade union in the workplace that can prevent employers from violating labour law and, at the same time, help workers improve their pay and working conditions through collective bargaining with management.

The All-China Federation of Trade Unions claims to have embarked on reforms that will make it more relevant to ordinary workers. On the evidence of the documented strikes and collective protests in China last year, it still has a long way to go. The Jasic workers understood the importance of union reform, hopefully in 2019, more workers will follow their lead.

For the Chinese version of this article, please see 2018中国劳动关系概况回顾.