On 23 November, a migrant worker using the pen name Chen Zhi made waves across social media when he was profiled on Tencent’s Guyu Lab, in a piece entitled “It is normal for a migrant worker to think about Heidegger!” The profile explores Chen’s complex life as a university dropout, a migrant worker and a self-taught philosopher who translated Richard Porter’s Introduction to Heidegger, a text on well-known 20th Century German philosopher Martin Heidegger.

Leading state publication the People's Daily joined the conversation by opining that everyone has the right to seek deeper meaning in their life. However, the piece ignored Chen’s reflections on the physical, mental and spiritual harm he’s endured as a migrant worker. This reaction from a leading media publication is surprising, as Chen’s story is not a new phenomenon in China.

Though Chen is but one person, millions of China’s workers have also searched for deeper meaning in their labour. One example is the “smart” culture of the late 2000s, in which young migrant workers far from home flaunted wild hair styles and loud clothes as a way to create community. Another recent phenomenon is of workers “lying flat,” a mindset to cope with long hours and burnout in typically white-collar workplaces. The example of Chen Zhi and these broader movements point to a deeper problem: Many workers are doing fatiguing, stressful and at times dangerous work in China, and not only are they physically or mentally exhausted, but also they feel a philosophical disconnect from the workplace.

After dropping out of university in 2008, Chen travelled among Beijing, Guangdong, Zhejiang, Jiangsu and Fujian as a migrant worker. “The longest job I've had was about half a year... The most tiring job was moving goods in Wuxi in 2018. There, I worked for more than two months, 12 hours a day, from 11 in the morning to 11 at night, with no rest.” For this work, Chen received monthly wages of less than 5,000 yuan and could only rent derelict apartments, sometimes lacking even basic features like toilets or windows.

Along with difficult working conditions, Chen also describes how the work’s monotony exhausted him mentally:

My first job was in Zhejiang, where I worked at a sewing machine in a garment factory… After working for a month, my salary was only 500 yuan. Operating the sewing machine was very difficult for me, and I needed to step on the pedals constantly. For my second job, I went to a factory that made instant noodle packages… That job was also done with a machine. I used the machine to roll paper, until the roll was finished. It was very rote, but also very tiring.

Chen’s breakthrough came after moving to Xiamen, where he published his first major translation in the Heidegger Douban group. He completed the translation over four months, during small breaks at work. But despite the personal accomplishment, Chen's work life felt more exhausting than ever:

There are no windows here, and the time is only displayed on the computer. The company’s computer can only access the company’s website. It’s terrible . . . I don’t have a stool to sit on, I just stand all day long. It is impossible to play with a mobile phone, because you’re not allowed to bring your phone in. Nothing can be brought in, only workers can enter... I don’t think about anything in the workshop every day. If you need to repair the machine, you just repair the machine. If someone talks to me, I will talk. Usually, no one talks, we all just are in a daze. In such an environment it’s impossible to think about Heidegger. It's too boring.

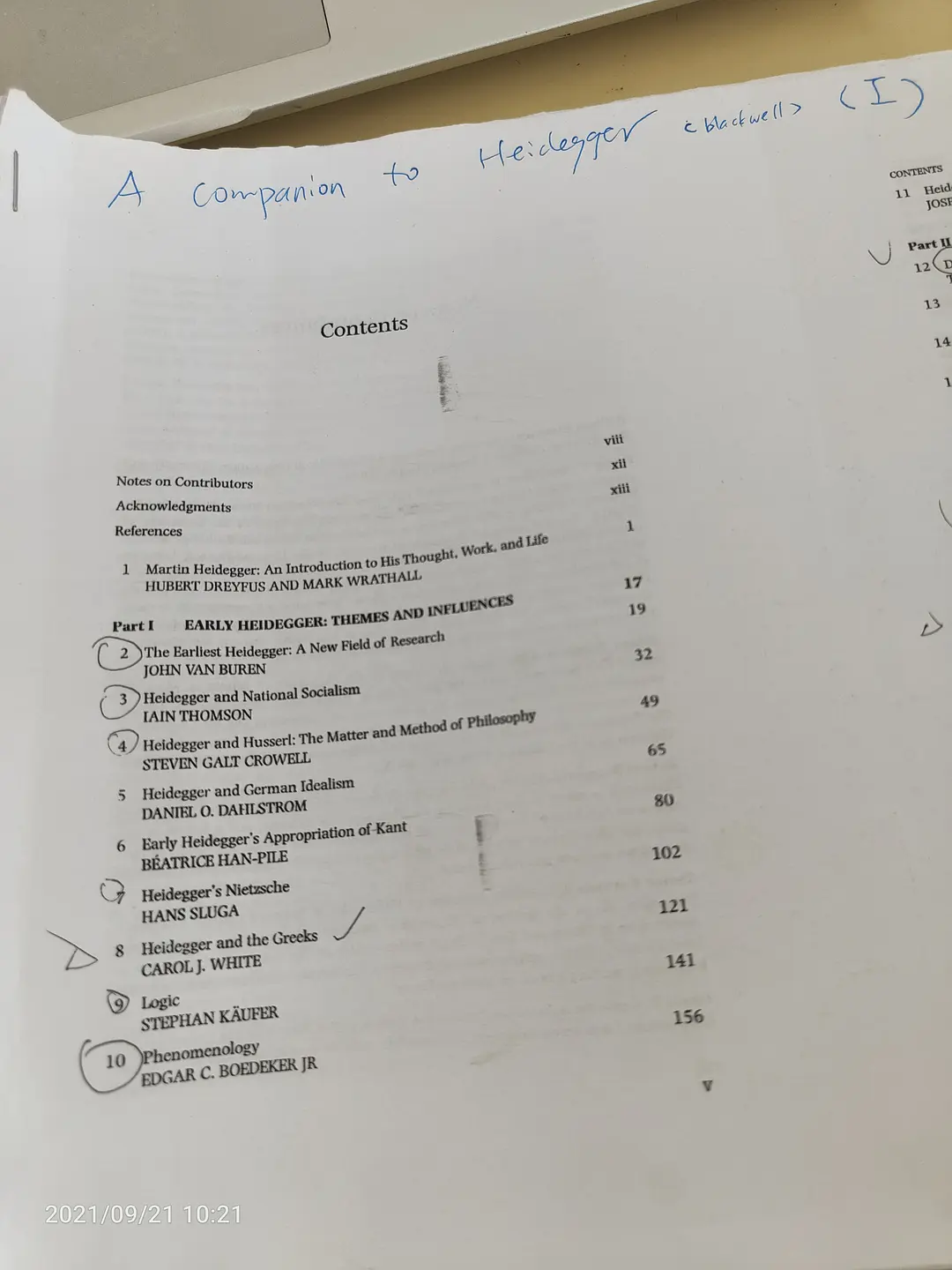

Chen’s annotated copy of an English language text on Martin Heidegger's work. Photo by Chen Zhi via Douban.

Even though Chen had online supporters, they were realistic with him that without connections to academia, the chances of finding a publisher were slim. With no real hope of his efforts being recognised, he resigned himself to a life of anonymous survival on the assembly line.

Whether you are studying mathematics or philosophy, you still have to face some basic survival problems. Now, through part-time work, I earn 4,000-5,000 yuan a month, which is only enough for food... On the assembly line, we work one by one. From 8:30 in the morning to 8:30 in the evening, 12 hours, one hour to eat at noon. There is a night shift every other month. As long as there's work to be done, the machines don’t rest, and as long as the machines don’t rest, we have to keep working forever.

While using one’s personal time to study philosophy may be unique, in the factory Chen Zhi is just one of many ordinary workers who form the backbone of China’s labour force. Recent policies discouraging the long office hours of 996 culture, as well as encouraging unions for delivery drivers in major metropolitan areas are positive steps, but Chen’s example and recent movements have raised unanswered questions about the physical, mental and “philosophical” exhaustion of China’s labour force.

All workers deserve to feel that their contributions are meaningful. Rather than be dismissive of this reality, state media should be listening more closely to workers like Chen Zhi and help them encourage workplaces to provide healthy and meaningful labour.