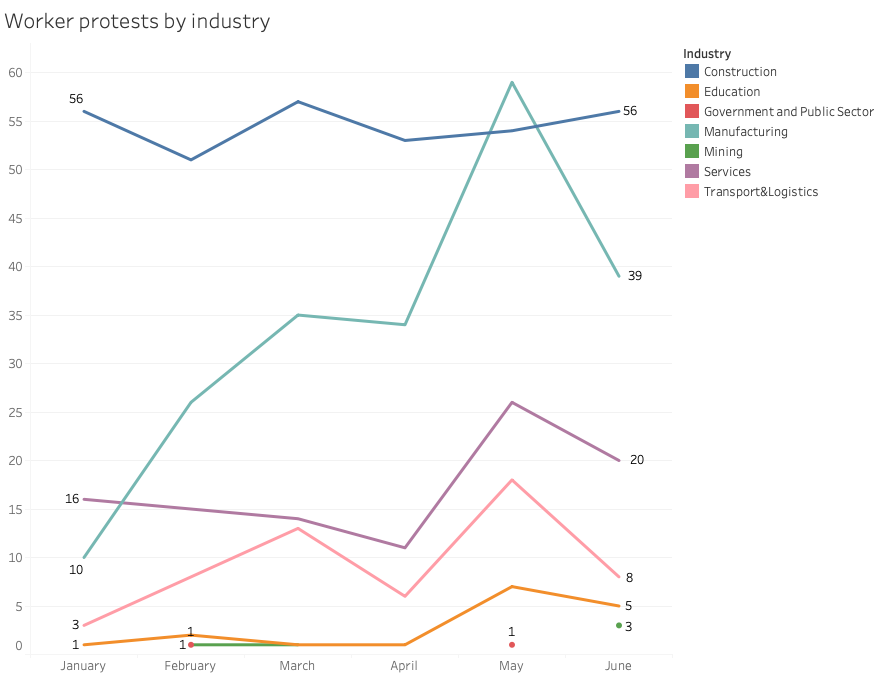

In the first half of 2023, China Labour Bulletin’s Strike Map recorded 741 incidents, catching up with the 2022 annual total of 830 incidents. Monthly totals in 2023 have risen month-on-month, with 86 in January to a peak of 165 in May. If this trend continues, a conservative estimate of 1,300 incidents in 2023 would reach a post-pandemic high and come near to the 2019 figure of 1,384 incidents collected.

From an industry perspective, manufacturing has seen the greatest increase in strikes and protests, from 10 in January to 59 in May. In the construction industry, workers have consistently protested over wage arrears at a rate of about 50 incidents per month. In the service sector and transportation industry, our map collects about 10 and five incidents per month, respectively. Although workers in the education industry and mining industry have not been frequently protesting, the rate has increased slightly since May.

Table of Contents

Manufacturing industry: Electronics and garment factory workers face brunt of shutdowns and relocations

In May, CLB analysed the sharp rise in worker protests sparked by a wave of factory shutdowns and relocations, particularly in coastal regions. Because of this obvious economic trend that leads to workers demanding their rights, CLB has urged the authorities and the official trade union to proactively seek ways to represent workers’ interests in negotiations, not only at the local level but also up the supply chain.

Other than a short rebound after the Lunar New Year, China’s total export value has been declining since June 2022. Caixin noted that the Purchasing Managers' Index (PMI) - which is an indicator of economic trends in the manufacturing and service sectors - has remained below 50 in China since August 2022, indicating that production is still expected to contract. With Europe and the U.S. also in economic contraction, overseas orders have dropped. Trade disputes have also contributed to instability in the manufacturing sector.

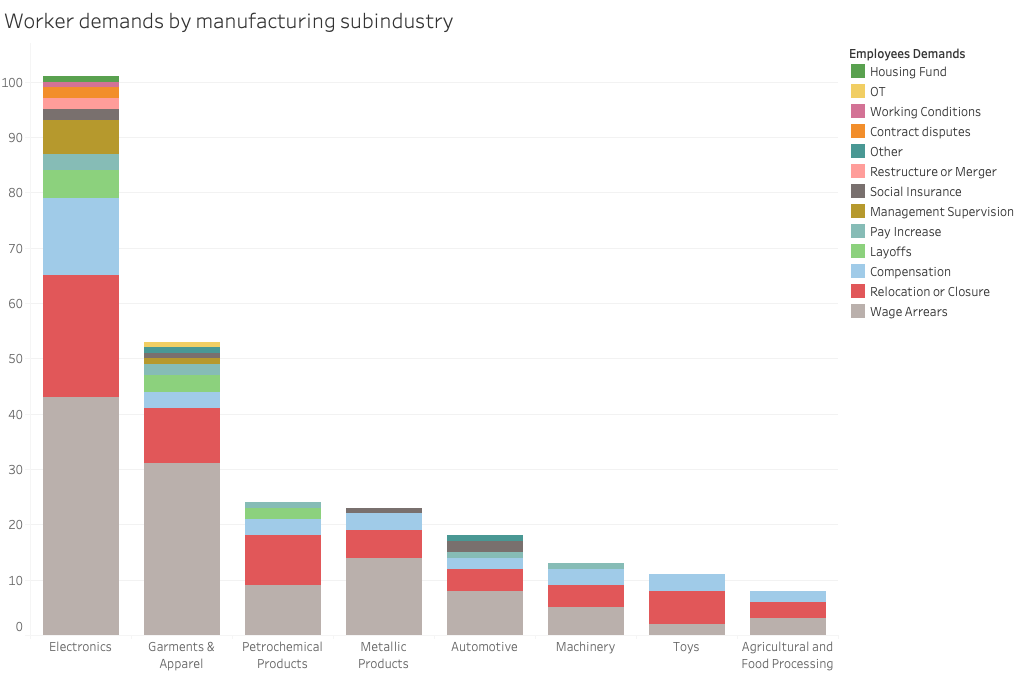

The electronics sector and garment and apparel sector have been hardest hit. These industries are concentrated in Guangdong province. In the first half of this year, our map collected 66 protests by electronics factory workers. For workers in garments and apparel, we collected 38. These two sub-industries account for over half of all manufacturing sector protests we recorded in the first half of the year. The remaining incidents were in metallic products (18), petrochemical products (14), automotive (12), machinery (9), and toys (6), etc.

The most common worker demands in the manufacturing sector related to factory relocation and closure. In the electronics sector, workers had the most diverse set of demands. Not only did they protest over economic concerns including wage arrears and lack of compensation for relocation and closure, but also they expressed dissatisfaction with company management decisions and over terms of their contracts. These demands largely stem from practices in which - instead of terminating workers’ contracts and paying compensation - the factory transfers workers to other positions, asks them to sign new contracts, or conducts disguised forced resignations.

An example is the situation of Foxconn workers in Zhoukou, Henan province, protesting in May 2023. The Innovative Level V Group (iLVG), which produces mobile phone accessories, was closed due to insufficient orders. Some workers in this department had initially been transferred to Zhoukou from Shenzhen, so when the iLVG department dissolved in May 2023, the workers believed they should be transferred back to Foxconn’s Shenzhen plant. However, the Zhoukou management transferred them to a small metal parts division. This forced transfer was viewed as a disguised way to lay off workers from the iLVG division who would be dissatisfied with the new position.

Compared with the worker response to the 2013-2015 wave of factory relocations, the current scale of strikes by workers in the electronics industry is relatively small. The CLB Strike Map records that about 40 percent of electronics sector protests involve between 101 and 1,000 workers, and the majority involve less than 100 people. When protesting, workers who are dissatisfied with unpaid wages and the situation of factory shutdowns and relocations often gather in the open, outdoor areas of the factory site, or at the administrative offices. Sometimes workers block the factory gate. The goal is for workers to pressure management to explain the arrangements and compensation plans, to pay workers their wages and benefits, and pay compensation for employment changes according to China’s labour laws.

In the garment and apparel sector, not only was the frequency less than in the electronics sector, but also the scale of protests was smaller. Many of the incidents were sit-ins with less than 100 participants. Workers also had less diverse demands, with 31 out of 38 incidents over wage arrears. Workers’ demands included compensation only three times. This may be related to the size of China’s garment and apparel sector, which is smaller than the electronics sector. In addition, the financial capacity of these factories to pay workers is lower. In fact, about 70 percent of the garment and apparel factories that recorded worker protests in the first half of the year were private enterprises, which are typically smaller. About 20 percent of the incidents occurred at factories owned by the typically larger Hong Kong-, Macau- and Taiwan-funded enterprises.

Construction industry: Real estate slowdown leaves workers without pay, particularly in China’s largest cities

China’s construction industry has remained the leader in the worker protests recorded in the CLB Strike Map. In the first half of this year, the industry logged over 50 incidents each month. As China’s real estate market is contracting, some companies have a surplus of vacancies, leading to difficulty paying contractors. This leads to worker protests over unpaid wages. Protests at residential construction sites (111 incidents) accounted for one-third of the total recorded so far this year , followed by shopping malls (79 incidents) and infrastructure projects (22 incidents).

Based on information gathered from social media, many of the construction sites affiliated with large real estate companies are seeing wage arrears after completion of the project. This is because subcontractors have not been paid, and are therefore unable to pay workers. For example, in early June, a migrant worker in Weinan, Shaanxi province, posted online that he and fellow workers have gone unpaid since 2021 after working on a hydropower installation project for a Country Garden Emerald Times project. The worker reported that the developer and subcontractors were in the midst of a dispute, and even if the workers took the case through legal channels, they believed the company would ultimately not pay the wages and would instead draw out the process through appeals.

Another type of labour incident occurs when a project is suspended due to lack of funds, and workers are not paid for labour performed on the unfinished project. In February 2023 in Wuhan, Hubei province, a post likely from a dissatisfied property owner stated that the Sunac 1890 real estate project had been suspended. Attached to the post was a photo of workers holding a banner asking for wages. The poster also wrote online, “The construction site only has a few people working there, as if they are performing construction, but not doing the real work. Yet workers are owed wages and have gone there every day to appeal.”

Photograph: hxdbzxy / Shutterstock.com

A similar incident happened in Xi’an at the Aerospace High-Tech Yuerong Garden property. In April, an online post revealed the site’s default on payments for structural work. A migrant worker surnamed Zhang found that work on the construction site had been suspended, and the only activity at the property was one security guard at the gate. Although worker Zhang and over ten others had completed their work in September 2022 and received a payment guarantee from the Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development, they had only received part of their wages at the time of the social media post.

Geographically, construction worker protests occurred most commonly in Guangdong province (83 incidents), followed by Shaanxi (39), Henan (22), Zhejiang (19), Shandong (18) and Sichuan (16). Most of these provinces have seen large population growth in the past decade and are now experiencing an oversupply of properties. China’s seventh national census in 2020 reported that Shenzhen and Guangzhou ranked first and second, respectively, in annual population growth. These cities added about 7 million and 6 million permanent residents, respectively, since the previous census in 2010. Of the new first-tier cities announced in 2023, Xi’an, Shaanxi province; Zhengzhou, Henan province; Changsha, Hunan province; Chengdu, and Hangzhou, Zhejiang province, are the next-fastest growing.

The last decade’s growth in China’s first-tier cities means that enterprises and workers have become concentrated in the industrial and commercial districts, stimulating the development of construction and real estate. The related wage arrears in the industry have exploded along with the rapid urban construction. The recent real estate market troubles have exacerbated the problem. CLB’s Strike Map shows that since 2016, many of the new first-tier cities have had a high incidence of wage arrears in the construction industry. Compared with 2011-2015, these more recent incidents are relatively more concentrated in Guangdong and Henan provinces.

Service sector: Traditional retailers lay off workers and owe salaries

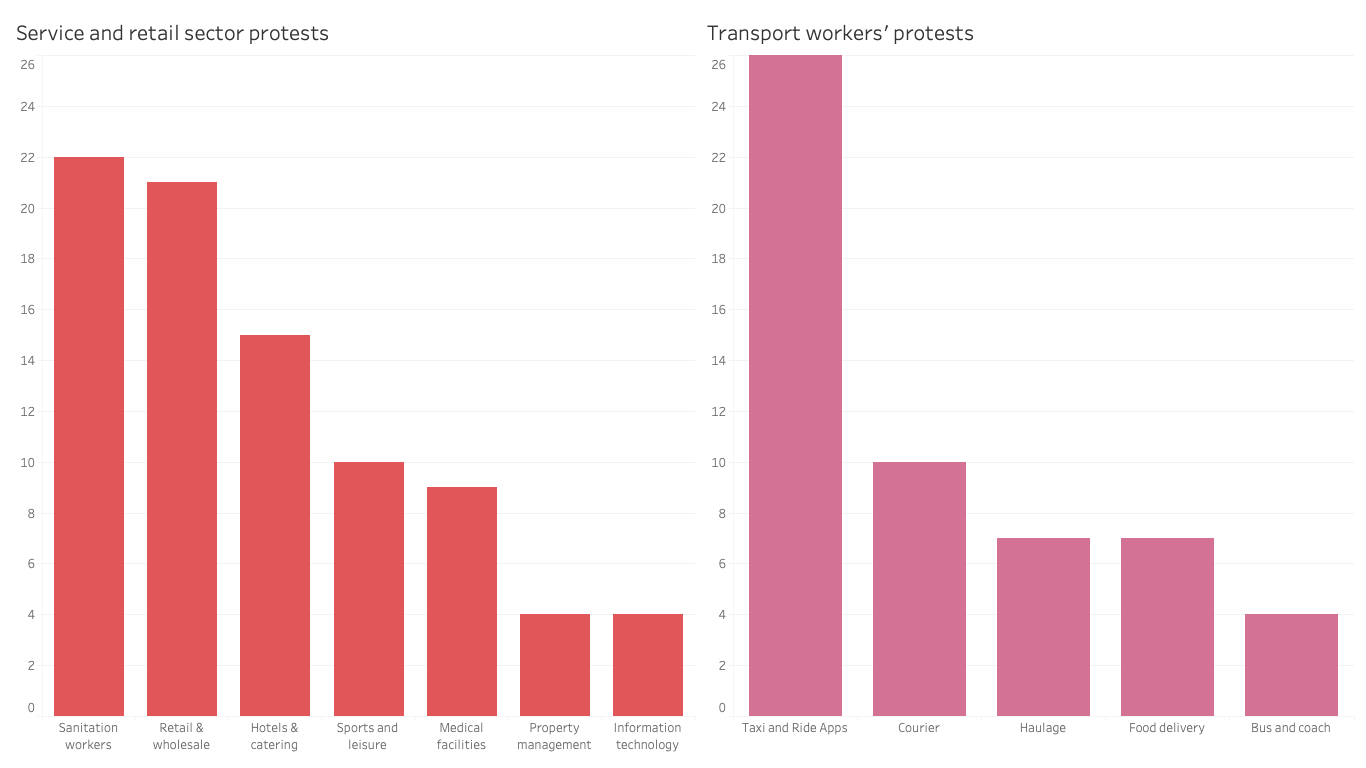

Service worker protests rank third in our map data, behind construction and manufacturing, with an average of 17 incidents per month in the first half of 2023. The most common demand is to recover wages owed, and the incidents are concentrated in sanitation (22 incidents), retail and wholesale (21 incidents) and hotels and catering (15 incidents).

The traditional retail industry is facing competition from e-commerce platforms, and the effect of the pandemic in the past two years has led to the closure of many outlets of brick and mortar hypermarkets and supermarkets, which has led, in turn, to defaulting on workers’ wages. CLB pointed out in our analysis of 2022 annual map data that the protests by wholesale and retail workers revolved around the transformation of the retail industry, and that trend has continued in 2023, as we see through retail worker protests this year.

Since January, Carrefour has continued to close some individual stores and incur wage arrears to employees. Carrefour stores across China have been reported for forced layoffs and delays in payment of severance compensation. Carrefour is known for first introducing foreign hypermarkets to China. However, after experiencing competition from local supermarkets and the rise of e-commerce platforms, Carrefour China has been losing money year after year, and its operating income has continued to plummet.

Another troubled retailer is Better Life Commercial Chain Store. In May, Better Life supermarkets in several cities in Hunan province announced their closure one after another. Workers said, "Better Life, which used to be prosperous in the past, cannot even pay basic wages now." Workers gathered in front of one of the closing stores to protest, and some workers threatened to jump off the roof, demanding that the company pay social security and overdue wages.

The sanitation industry absorbs a large number of older workers, including migrant workers, and it sees a high incidence of wage arrears. Sanitation companies often state that they have not received funds from the contracting party, which in many cases is the government, so companies default on wages and pass on the problem to workers. In May, in Fuzhou, Fujian province, workers protested and sought assistance from journalists, saying they had not been paid since February. A representative of the sanitation company said that the cleaning fees had not been paid by the real estate service company according to the contract since December 2022, and this was the reason for the wage arrears. After workers protested, the company stated it would pay in full by the end of the month.

Transport and logistics industry: Workers for new and old transport modes resist oppressive working conditions

As has been the case for years, collective action by workers in the transport industry has been dominated by taxi driver protests. A total of 26 such protests were recorded in the first half of this year. As a more traditional mode of transportation, taxis are deeply affected by the competition from unlicensed taxis and online ride-hailing platforms. Taxi drivers have also protested against the proliferation of shared electric bicycles.

In addition, the authorities have regulated taxis to require new technology upgrades, like electric vehicles. Drivers have pushed back against this, and also protested issues like high petrol prices, unregulated taxis, and low base fares. Taxi management companies have engaged in exploitative practices, and drivers have protested to demand the integration of management rights and property rights over their vehicles, and against high licensing fees.

To cope with these changes and adverse conditions, taxi drivers have increased their working time and intensity to try to earn a higher income. This has its negative long-term effects; there are occasionally reports of taxi drivers collapsing from overwork.

Photograph: Rob Crandall / Shutterstock.com

As for newer transport and logistics industry protests, workers largely protest against platforms’ declining unit prices. The CLB Strike Map recorded three strikes by couriers in March and April, including Meituan food delivery riders in Shanwei, Guangdong province. In that case, continuous and heavy rains affected the region, but Meituan cancelled riders’ inclement weather subsidies and lowered unit prices. When workers went on strike, the company called in riders from other regions instead of ceding to local riders’ demands. In the end, after the incident received attention online, Meituan restored the unit price and partially restored the rider subsidies.

Drivers of Huolala (Lalamove), an online freight platform, launched several strikes in May. Huolala drivers in Chengdu; Chongqing; and Liaocheng, Shandong province, were dissatisfied that Huolala had reduced freight prices four times consecutively, and that other policies had cumulatively lowered drivers’ incomes. These policies are designed to attract customers to the platform, but drivers said they are the ones who pay the price. Huolala has also squeezed the incomes of drivers by increasing membership fees and platform commissions.

Official responses from trade union and authorities have not been enough to protect labour rights

As worker protests and strikes once again rise as the post-pandemic environment normalises, China Labour Bulletin has taken note that some levels of China’s official union, the All-China Federation of Trade Unions (ACFTU), have taken the initiative to become involved in some collective actions. However, the effect of trade union intervention is quite limited, and the process is still deeply inhibited by bureaucracy.

In some cases, the actions of trade unions even directly conflict with the interests of workers. For example, during the relocation protest of the Welfare Electronics Factory in Shenzhen in April 2023, the enterprise trade union was willing to negotiate with the factory on behalf of the workers, but when the enterprise union asked the street-level union for support and coordination, they flatly refused.

Another example is that workers at the Quang Viet Garment Factory in Jiaxing, Zhejiang province, launched a strike in April to demand a wage increase. The trade union intervened in the strike to encourage a resumption of work, but the union did not advance the workers' demands.

And when workers protested in May at the Xin’an Electric Factory, they demanded that the factory pay overdue social insurance and other benefits. But CLB found that the union had previously approved the company’s application to the local housing provident fund department for a reduction in the contribution ratio.

The number of incidents in which police are dispatched to the scene of worker strikes and protests has increased significantly. In the first half of this year, CLB’s Strike Map recorded 82 incidents in which the police were dispatched, nearly double the 49 incidents last year. In seven of those incidents, workers were arrested for protesting for their wages and other compensation.

The dissatisfaction raised by many workers - from wage arrears, to relocation compensation, to payment of social security and other benefits - is not a one-off situation. By the time workers protest, enterprises have usually been stuck in production difficulties for several months or even an entire year, with declining orders and a shortage of funds, and workers have been unpaid for several months.

Trade unions can step up their work and act according to their mandate by strengthening their relationships with enterprise trade unions and proactively intervening to assist individual workers. By doing so, they can easily detect changes in the business environment before problems arise, and act in time to prevent violations of workers’ rights and subsequent collective actions.

Further CLB reading: