- Food delivery rider Yang Xiaobing needed leg surgery after a traffic accident while making deliveries in Hebei, but he didn’t immediately have the funds.

- Applying for work accident certification takes time - and the employer’s cooperation - and insurance he paid for through the platform company was not available.

- Through a WeChat group for riders, the funds for Yang’s surgery were crowdsourced in just ten days.

- CLB reached worker Yang while he was recovering, and we also called the relevant district and municipal unions to urge them to better protect the rights of workers like Yang.

In an online appeal for mutual aid, food delivery rider Yang Xiaobing is described as “a good husband who loves his wife” and “a guy who persistently sustains his whole family.” Yang’s leg was broken on 28 February 2023 when a large truck collided with his food delivery bike in Hebei province, just east of Beijing.

Yang is part of a WeChat group for riders, and he reached out to this network for help. The well-known worker organizer Chen Guojiang - known as Mengzhu or “Leader of the Riders’ Alliance” (外送骑士联盟盟主) - reposted Yang’s story and asked riders to chip in. Mengzhu’s crowdfunding appeal read, in part:

Yang Xiaobing’s family has been in difficulty for a while. His wife has depression and can’t work, and the money Yang makes from delivering food first goes for her to see the doctor. But things do not always work out for good people.

Through this direct crowdfunding method, in just ten days the group was able to come up with the funds Yang needed for his leg surgery.

A video screenshot of Mengzhu with the text, “Hello everyone, I’m Mengzhu, the leader of the rider’s alliance.”

Behind this example of riders organizing to extend their generosity lies a web of labour rights challenges in the platform economy that urgently need official attention. As Mengzhu wrote online:

I don’t know if it is me who is “ill,” or if it is society that has the “illness.” Many food delivery riders have endured so much these past several years, but nobody cares about them when they encounter tragic accidents. So I don’t know who is sick: society, the food delivery platforms, or we riders. Who can answer me?

China Labour Bulletin suggests that China’s official trade union should pay attention to Mengzhu’s question and seek a solution to riders’ problems.

Platform workers’ unclear labour relationships mean work accident compensation is often out of reach

When China Labour Bulletin found out about Yang’s case, which we collected in our labour rights map database, we were able to contact Yang directly on 8 March.

Yang told us that his troubles did not begin with his accident in late February 2023. As a food delivery rider during pandemic lockdowns, he faced restrictions on his livelihood at a time when his delivery services were needed most by society.

Yang said that the lockdowns would come so suddenly: “Just one sentence and you’re locked at home.” Yang continued:

We tried many times to appeal against the lockdown policies for delivery riders, but it is useless. Nobody cares. The city level and the county level both shirk responsibilities off on each other. We have endured too many unfair things during those three years. Things… life at the bottom… you can't imagine.

Yang is familiar with the administrative process of certifying a workplace injury to receive compensation. He told us he was injured twice in the past on different jobs, and in neither case was the outcome successful. In one case, while working at a state-owned enterprise, his injury was certified as work-related, but in the end he never received compensation. In the second, his application for work-related injury was never certified.

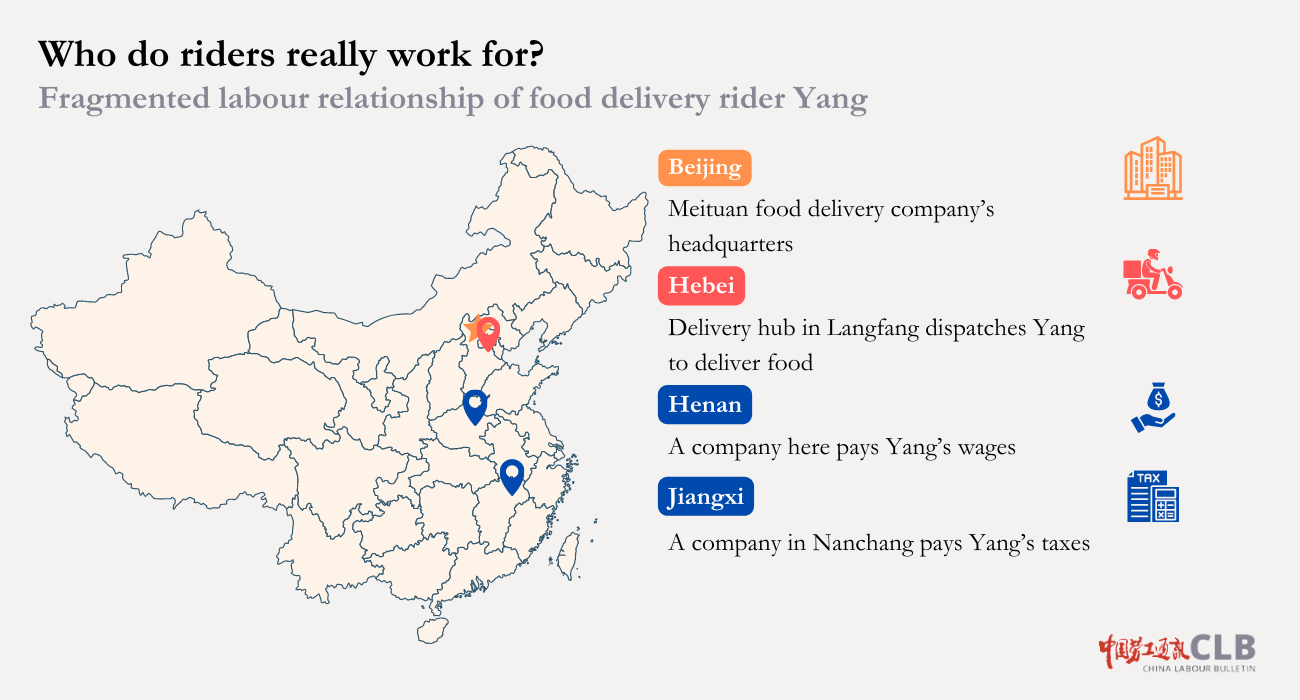

The labour relationships in Yang’s current case are not straightforward. He rides for Meituan, but on the phone with him, we uncovered that a company in Henan paid him wages, a company in Nanchang, Jiangxi province, paid his taxes, and he was dispatched from a delivery hub in Hebei province near Beijing. Because these entities are across different jurisdictions, he would have to contact numerous local government bureaus to get anything sorted.

At the time we spoke with Yang, he was still in the hospital recovering from the leg surgery and told us that his family members would not have the wherewithal to complete the administrative process on his behalf.

Riders’ medical insurance is wrapped in red tape and can’t be accessed in time for urgent medical needs

The process for obtaining workplace injury compensation through official certification is one thing, but what about medical insurance or workplace accident insurance to cover Yang’s immediate hospital bills?

On the riders’ crowdfunding page for Yang, Mengzhu explained the problem:

Even though we have public health insurance, and even though Meituan Crowdsourcing deducts fees for accident insurance, we each need to chip in [to help Yang]. We know that the platform has never cared about us - we have to go through labour arbitration to confirm labour relations first when we are injured - yet every single day they take this three yuan from us for “accident insurance.”

These kinds of red tape prevent riders from accessing their rightful compensation and insurance benefits at the time they are most needed.

China’s official trade union has a role to play in remedying these systemic labour issues and filling gaps when official systems fail. When Yang got injured riding for Meituan, he told us he initially reached out to a level of China’s official trade union in Beijing for Meituan Crowdsourced riders. That union agreed to donate 100,000 yuan to Yang for his injury. But because Yang is a Hebei rider, the funds were not permitted to be donated across administrative lines.

We suggested that Yang try contacting the local unions in Hebei, but he told us he felt better off going through the free legal services provided by one of the crowdfunding platforms riders used to donate.

Photograph: Wang Sing / Shutterstock.com

On 8 March, CLB called the local trade union in the Sanhe district of Hebei, where Yang made deliveries every day, to see if they could help fill the gaps for workers in their district. We spoke with Mr. Zhang at the Sanhe district union, who simply told us, “You need to find the social security bureau, as the trade union only provides free lawyers for workers to consult.”

We then called the union’s lawyers, who told us that their services are merely to advise workers. If a worker decides to pursue a legal case, they can do so on their own.

If the district union does not have the resources or services to help workers whose rights are infringed, surely the next level union would have some answers. In fact, the Langfang municipal union in June 2022 launched a special campaign to unionise gig workers:

The union will establish the confidence and determination to dare to fight tough battles, set high goals, apply self-pressure, push forward, and make every effort to ensure breakthroughs in this work… We regard new employment forms as an important indicator for year-end evaluation of county-level trade unions.

However, the municipal trade union told us when we called on 8 March that joining the union was voluntary, and that anyway they could not go against the Sanhe district union’s assessment. In this way, the bureaucracy within the union hierarchy inhibits the union’s core function.

Food delivery workers need representation to remove barriers in their way of accessing labour rights

China’s official trade union recently disclosed survey results showing that the total number of workers in China is about 402 million, of which 84 million (about 20 percent) are in new forms of employment. In other words, one out of every five workers is in a job that falls outside regular labour protections. The number of food delivery workers in China reached 13 million, according to Caixin’s estimate in 2021.

As Mengzhu wrote on Yang’s crowdfunding page:

As food delivery riders, you all know that in this industry, we work hard every day in all sorts of weather conditions, and the thing we are most, most, most, most scared of is an accident on the roads.

Yang’s case illustrates how the difficulties of a traffic accident extend beyond the pain and suffering of the injury and the missed income while recovering. When food delivery riders “get sick,” they come face to face with what Mengzhu calls the “illness” of platforms and society, and - as CLB found - the bureaucracy of official structures including the union.

Photograph: YPPicturesPro / Shutterstock.com

The state has issued some regulations and guidelines on platform companies, but workers like Yang face fundamental challenges that top-down policies fail to change. What workers need is representation before industry leaders to ensure that workers have access to their rights, including workplace injury compensation and workplace accident insurance.

CLB urges for China’s official trade union to engage in industry negotiations on behalf of workers for improved insurance benefits, work safety guarantees, and clearer labour relationships.

Further CLB reading:

- Food delivery workers need a trade union to push for real change (September 2020)

- What You Need to Know About Workers in China: The Platform Economy (updated April 2023)

- Food delivery worker activist accused of “picking quarrels” (March 2021)