CLB launched its Workers’ Calls-for-Help Map at the end of 2020. Since the map went live, we have recorded 1,261 incidents of workers seeking help in their labour disputes online. Looking back at the past year, we found that young people who work in retail and the service industry are increasingly posting to social media to resolve labour disputes with their employers.

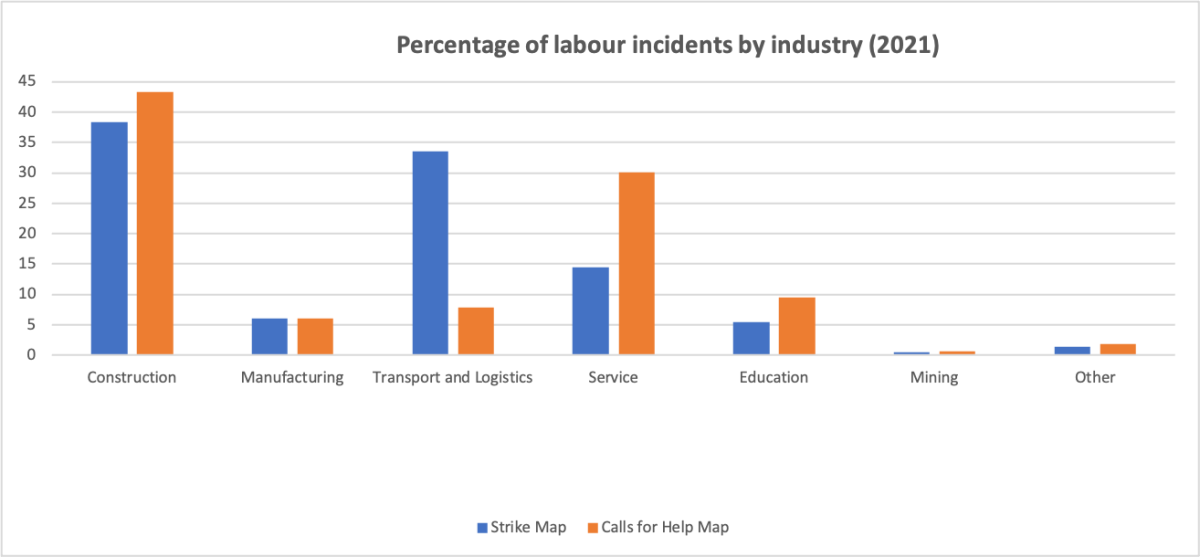

In both our Strike Map, launched in 2011, and the new Calls-for-Help Map, construction workers account for the majority of all cases collected in the maps. When it comes to individual calls for help, service industry workers came in second behind construction with over a quarter of cases logged. This is compared to collective actions of service sector workers, which only accounted for about 15% of cases in our Strike Map in 2021, lagging behind not only construction but also the transport industry.

Service workers often work for small and medium-sized businesses in the e-commerce, media, and cultural products industries. Many of these companies are new, following a trend of startups, so competition is intense. Losing market share means that companies overwork their employees, withhold regular wages, and even stop paying them altogether because of bankruptcy.

When this happens, these workers rely on their ability to express themselves online, as well as existing legal channels, to protect their rights and interests. Workers posting about their labour grievances tend to be younger than the average construction worker, and some are recent graduates or seasonal workers. Usually, their first attempt is to talk to their employer directly to resolve wage-related issues, and they only move on to the time-consuming process of labour arbitration when their negotiation efforts lead nowhere.

Worker experiences

Workers are the ultimate victims when small companies can’t compete in the market and face cash flow issues. For instance, Shanghai Yanjiyou, which sells books, cultural products and coffee, has faced financial difficulties since 2017. Employees had to pay for the tea and fruit sold in the store using their wages, and, since 2020, they only receive their wages every two months. Some former employees were owed several months to half a year’s worth of back pay. Often, managers would convince employees to stay with promises of repayment in a few months’ time.

Workers tend to tolerate this precarious wage situation, sympathising with the company and even living off their savings. In 2021, workers wanting to leave the company found that despite not receiving wages, the company still expected them to sign non-compete agreements or that their contracts included left blank spaces that the employer later filled in as they wished.

“I really couldn’t agree to it,” an employee wrote online about staying on at the company. “After five years of working conscientiously, I ended up here… now I’m just an average, angry, former employee who is owed wages.”

Student workers face even more difficulties. In June 2021, a student who was working at Shijiazhuang Zhenshuo media company found that after apologies and promises that his salary would be paid, the company just disappeared. Though the student reported his issue to the district’s labour inspectorate and other authorities, they said that his status as a student meant that he did not have a legal labour relationship with the company, and they advised him to find a lawyer.

“Bringing this case costs 5,000 yuan [U.S. $785], which is more than my salary,” the student said. “If I could afford a lawyer, why would I still be working and studying?”

Photograph: Robert Way / Shutterstock.com

When these small companies are facing a real crisis, they don’t have the cash to pay wages. In normal times, however, they also tend to overwork their employees. In December 2021, a graphic designer surnamed Liu worked on the user interface for Xuecai Network. Liu said that he was made to do tasks outside the scope of his designated role creating anime gaming content. The company consists of a producer, a manager and a human resources staff. There was neither strategy nor process to ensure decent pay for decent work.

“Small companies in China are all like this,” Liu wrote on social media. “I didn’t say anything because I was in a hurry to find a job.”

The small size of such companies also means that they can evade government and media scrutiny. Though the government has stated that it wants to do away with 996 working culture, which violates China’s Labour Law, internet companies are getting employees to work six days a week, every other week.

In this case, Liu said that the requirements on him were “PUA,” meaning the employer was acting like a “pick up artist,” a term borrowed to describe emotional abuse at work.

Liu worked overtime, on a 996 schedule. When he wanted to become a regular worker, his company denied his request, accused him of not fulfilling his duties, and extended his probation period for another month. For that month, he continued to be paid 20 percent less than his promised salary. He left the company before the end of his probation period.

When he filed a labour arbitration against the company, his employer responded with veiled threats, telling Liu, “The gaming circle is very small.”

He submitted all kinds of records to try to receive compensation for his overtime work, but the arbitration went in his company’s favour. The court said that Liu should have applied for overtime and that the extension of probation merited a payment to him of only 500 yuan.

“It’s laughable,” Liu said. “My many records lost against a few words with no evidence to back them up.”

At that time he was paying 2,000 yuan in rent, and the labour arbitration process had stretched to three months.

Though these types of workers generally have a higher level of education compared to construction workers and have better capacity to navigate the legal process, they are far more isolated in their grievances at small companies. They tend to be young people starting out in their careers. Their companies are very unlikely to allow them to start a union and they cannot rely on help from colleagues. Instead, they turn to voicing their distress online.

Many of these calls for help would simply get lost in the winds of social media. We collect them not just as data points about economic and labour trends, but also to find effective resolution methods for common issues.