Photograph: sleepingpanda / Shutterstock.com

Letter from the Editors

The China Labour Bulletin email newsletter now has a name: Bullet Points! We chose this name because it reflects both the brief insights we bring to you as well as our organization’s name and a bit of our history. You may not know that CLB was founded in 1994 in Hong Kong as a “bulletin” publication, both for workers in China and for trade unionists around the world. Still today, we publish in both English and Chinese to reach a wide-ranging audience (you!) about the labour rights situation in China.

In other news, at CLB we walk the talk on democratic processes at the workplace level. This month, CLB’s worker-management committee signed a new annual collective agreement with our Executive Director, Han Dongfang. Each year, CLB staff elect representatives to negotiate over working conditions, workplace policies and remuneration.

We periodically update some of our most popular resources: our series of research explainers in our What You Need to Know About Workers in China section of our website. The topic of workers’ rights and labour relations received a fresh update just last week.

Thanks for reading!

CLB Editors

What We’re Focusing On

Supply chains. After an 8 May strike by workers at a kitchen appliance factory in Shenzhen, CLB called the local authorities and confirmed that workers had been owed wages and benefits for some time. Moreover, the enterprise union had acted against workers’ interests by approving management’s proposed reduction in the percentage of housing provident fund contributions. About a hundred workers went out on strike (see photo, above) after the factory, Xin’an Electrics, announced its closure. The parent company of Xin’an Electrics is Hong Kong’s Simatelex, which has produced for major brands including Keurig, Cuisinart, and Philips. Simatelex is a member of the Responsible Business Alliance. CLB urged the local trade union to bring together stakeholders to make sure domestic law is followed and workers are compensated upon business closure. Read more about the workers’ strike and CLB’s interviews with local authorities and the union: Workers strike at kitchen appliance factory in Shenzhen, seeking wages and benefits after announced closure.

Digital surveillance. Delivery workers in Shanghai were singled out by the traffic police for a special operation to catch those violating traffic laws. Workers from a dozen or so platform companies were required in late 2021 to register their motorbikes with special electronic chip licence plates, and the June 2023 crackdown is catching workers running red lights through certain intersections equipped with sensors to track the new plates. Now, workers are in a Catch-22 where the platform’s algorithms and faulty map directions are pushing them to deliver more and faster, so they either get fined for late deliveries or fined for violating traffic laws. Read more on why we believe workers are one of the victims of Shanghai’s unsafe roads, not the root cause: Shanghai traffic police target delivery workers through electronic licence plate chip.

Worker Voices

Stand up for yourselves! Platform truck drivers went on strike in May for the second time in six months, over Huolala’s (Lalamove) corporate practices designed to gain market share at the expense of drivers’ bottom lines. One driver posted an appeal online for workers to resist:

Huolala drivers, can you stand up for yourselves? I’m at a loss to see why colleagues would yield to this platform designed to entrap drivers.

These reactive strikes have their limits. As platform companies’ business models are becoming unsustainable, Huolala will likely continue to extract more value from drivers in order to recoup their investment costs and improve its earnings. To go further in this environment, workers will need the support of China’s official union to effect change.

Safety First

What happened. Workers vulnerable to poverty are going to work in the phosphate mines in Leshan, Sichuan province, often bringing families and fellow villagers to work with them. The 4 June landslide that killed 19 workers at the Leshan Tuoda Mining Company has been attributed to a “natural disaster” and perhaps climate change, but regardless of the reason, rural families have been deeply affected. They are searching for answers about the safety measures taken at the work site. Workers said they had raised issues after a new mine was recently opened and slag was dumped too close to their work shed.

Connecting the dots. Notably, the phosphates mined in Leshan are used in batteries for new energy vehicles. China dominates the electric vehicle (EV) market globally, and this is no coincidence. According to the MIT Technology Review, China’s EVs use lithium iron phosphate batteries which are safer and cheaper than the alternative used in the West. China controls many of the materials necessary for their production. As Zeyi Yang writes, “China’s head start has given domestic companies a longstanding stable supply chain.”

Up close and personal. The role of workers across that supply chain should not be forgotten. One of the workers who passed away is Wang Mao. His relative described how Wang had faced difficulties supporting his family and two children. First, Wang was a food delivery worker, and then he joined an online ride-hailing platform and borrowed money for a vehicle before the platform went under. At that point, he went to work in the phosphate mine in Leshan, hoping to earn several hundred yuan per day. Wang’s family had reservations about his safety in the mines, and now the whole family is left to fend for themselves.

Strike Action

Factory worker strikes and protests continue. CLB’s Strike Map recorded 40 collective actions by factory workers in June 2023. This raw number is down from the new high of 59 recorded in May 2023, but the proportion of total incidents collected is still high, at 30 percent (compared with single digits for most of the past several years). Strikes and protests in the manufacturing industry mainly regarded payment of wages in arrears and compensation for factory closures and relocations. Out of the 40 incidents, eleven were in the electronics sector and six in garments and apparel.

Mining workers protest over unpaid wages. The mining industry is not known for strikes and protests in the last few years in China, so the three such incidents we recorded in June 2023 are noteworthy. At the state-owned Yingzi Copper Mining Company in Chengde, Hebei province, online videos show dozens of workers marching on the road on 8 June to demand payment of wages and pensions (see photo above). On 1 June in Xinjiang, workers protested at a coal mine in Ruoqiang county, and on 12 June in Guizhou province, workers protested at a mine by holding up a banner demanding wages. The scale of each of these three mining sector protests was relatively small, with under 100 people each.

Large-scale protest over iron and steel plant closure. CLB noted last year that due to changes in China’s real estate market, the iron and steel industry was negatively affected and shutdowns were likely. In early June 2023, the Tangshan Delong Iron and Steel Plant in Hebei province ended production, laying off over 3,000 workers. Many had worked there for over a decade or even since the plant was founded. On 1 June, over a thousand workers protested the compensation plan. Online sources indicate that at the end of June workers received one month’s wages for each year of service, and the average salary on which the compensation was based was increased from the initial offer. Workers received 100,000 - 300,000 yuan each in compensation for the closure.

Worker Representation

A video screenshot of Mengzhu with the text, “Hello everyone, I’m Mengzhu, the leader of the rider’s alliance.”

Mutual aid on the one hand… When workers fall through the cracks in the system, many do not have safety nets. In the case of a Hebei food delivery rider named Yang Xiaobing, he urgently needed funds to undergo leg surgery after a traffic accident while delivering meals in late February. The well-known worker organizer Mengzhu helped Yang crowdfund through riders’ WeChat groups, and Yang had the surgery ten days after his collision.

…versus union representation on the other. Yang’s case shows how workers in the gig economy are largely unprotected by China’s labour laws. Without formal employment contracts, workers are caught in a web of unclear labour relationships among a series of corporate entities between themselves and platform companies. This means workers have difficulty meeting legal requirements to access their labour rights. Workplace accident compensation and insurance through the delivery platform were both unavailable to Yang when he needed surgery.

CLB has urged China’s official trade union to fill these gaps and solve these systemic problems that affect China’s estimated 13 million food delivery riders. When we called the district and municipal union in Hebei, they simply told us:

The trade union only provides free lawyers for workers to consult.

When the union abdicates its duty to represent workers, it sets itself up for ongoing failure: workers have little reason to give the union the chance to represent them, leading to a vicious cycle that will only continue unless the union reforms.

CLB Insights

Workers’ rights in the heat. On 10 July, state media broadcast a video praising construction workers in Hebei’s Xiong’an New District for working in the above 40 degrees centigrade temperatures. The host used a digital thermometer to read the surface temperature of the roof, which was over 60 degrees. In the comments section, translated by China Digital Times, people strongly criticised the violation of workers’ rights:

Risking heatstroke to meet a construction deadline? Who forced them out there?

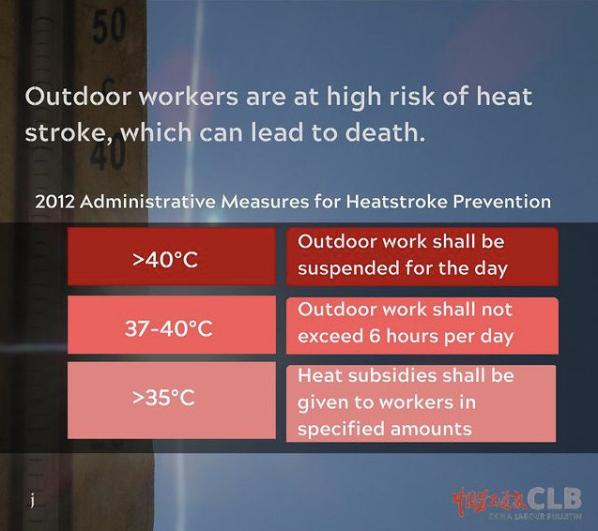

Workers whose jobs are outdoors or in enclosed spaces are at high risk of heat stroke and death. China’s 2012 Administrative Measures for Heatstroke Prevention specify under what conditions outdoor work must be suspended or reduced, and hot weather subsidies are mandated otherwise.

Not only are these subsidies quite low - and no amount of money is ever worth risking workers’ lives and health - but also the regulations are difficult to implement in practice. Employers sometimes only offer cool drinks, and workers have few labour incentives to request work stoppages or shift changes. It is also difficult to prove heatstroke as a work-related injury. With the increasing effects of climate change, China’s workers need better protections.

CLB in the News

Still in the spotlight. Our Strike Map analysis of a surge in strikes and protests in China’ manufacturing sector was featured by The Economist’s Drum Tower paid-subscriber email newsletter, under “What our journalists are reading.” Our piece uses select case studies of worker strikes to show how employers are navigating economic difficulty, at the expense of workers’ rights. We include a brief section on China’s labour laws governing compensation for factory closures and relocation, as well as CLB’s suggestion to involve suppliers, brands, and the trade union in negotiations to better protect workers’ rights.