In CLB’s research report 建筑行业工会归位: 我国建筑行业40年之“法外运行”及其出路, published in January 2019, we analysed the deeply ingrained and systemic problems affecting workers in China’s construction industry and suggested a way forward in the future.

In this English-language summary, we highlight some of the key extracts from the report that contextualize the development of the industry over the last four decades and reveal why construction workers are more likely than any other group to suffer from violations of basic labour rights, such as the non-payment of wages, and are more likely than workers in other professions to be involved in a workplace accident. In conclusion, we argue that China can no longer rely on legislative changes and administrative fiat to protect workers, and that only a strong trade union presence on construction sites can actually guarantee workers a decent wage and safe working conditions. Please see the original Chinese text for citations and detailed case studies.

Construction workers in Beijing. March 2013 by Joe Tymczyszyn. Photo available at Flickr.com under a creative commons licence.

The transformation of the construction industry

In the 40 years that have elapsed since the launch of China’s reform and opening up policies, we have seen substantial changes in the structure and operational model of the Chinese economy. In terms of ownership, the shift has been from monopolistic state-owned companies to a mix of public and private enterprises. In terms of operating model, the shift has been from a planned to a market economy; and corporate management has abandoned its bureaucratic style for a range of formats which prioritise profit. Probably the most dramatic change of all however has been in the construction industry. In fact, it would be no exaggeration to say the industry has experienced a revolutionary change, as illustrated below.

- In 1996, there were 9,109 state-owned construction enterprises in China, comprising 81 percent of all construction enterprises. In 2017, the number had dropped to just 2,187, accounting for only 2.5 percent of the total number of construction companies.

- In 1996, there were 1,601 joint-stock construction companies, accounting for 14 percent of all construction enterprises. In 2017, their number had increased to 32,894, accounting for as much as 37.3 percent of all construction companies.

- In 1996, the number of privately operated- construction companies in China was just 535, or 4.7 percent of all construction enterprises. In 2017, their number had increased to 49,645, comprising 56.4 percent of all construction enterprises.

- In 1996, the total number of workers employed in state-owned construction enterprises was 8.56 million, accounting for 92.5 percent of total employees in the sector. In 2017, the number had dropped to 1.83 million, just 3.3 percent of all employees in construction.

- In 1996, 600,000 people were working at joint-stock construction companies, accounting for 6.4 percent of the total of employees in the sector; in 2017, this number had soared to 28.28 million, accounting for 51.1 percent of all construction sector workers.

- In 1996, the total number of employees in private construction companies was 90,000, just 0.09 percent of the total number of employees in the construction sector. In 2017, this number had ballooned to 23.4 million, accounting for 42.3 percent of all employees.

- By 2017, the vast majority of employees in the construction industry in China were informally hired rural migrant workers rather than urban workers with a formal employment contract.

Rapid economic growth, combined with the privatisation of the construction industry led to the steady rise in the number of workers, employed in highly efficient construction teams, who have transformed China over the last four decades. They built the high-rise towers that dominate the new urban landscape, the high-speed rail system, and a vast network of roads, bridges and tunnels that now link just about every city, town and village, even in the remotest parts of the country. Entire new cities have sprung up over the last four decades, as well as new industrial and manufacturing zones, container ports and airports. In 1978, for example, China had just 78 commercial airports. In 2017, that number had nearly tripled to 229. In 1978, China had 890,000 kilometres of national highway and just 1,000 kilometres of expressway. By the end of 2017, those figures had risen to 4.774 million kilometres and 136,000 kilometres respectively.

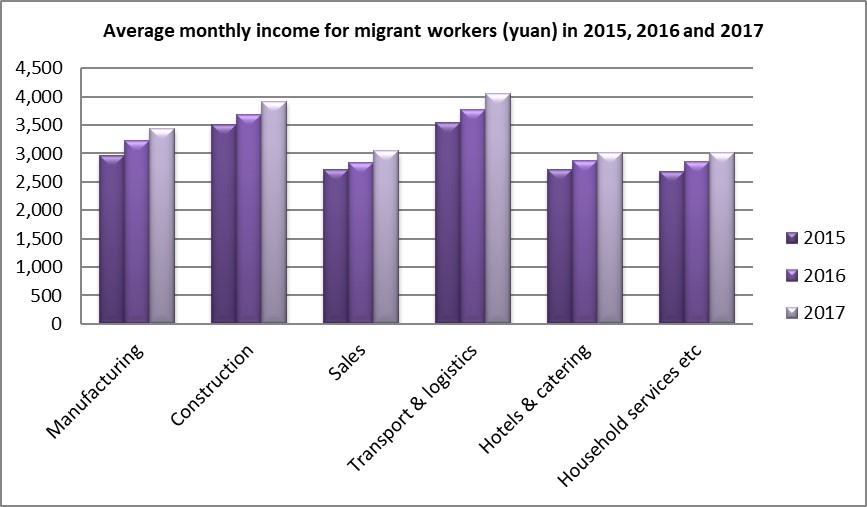

The efforts of China’s construction workers have revolutionised daily life in China – everything from housing, communications, travel and new patterns of consumption has been based on the hard work and endeavour of construction workers. However, the people who built the new China have yet to be adequately rewarded. In 1985, the average wage for China’s construction workers was about 787 yuan per month. By 2017, the average monthly wage had risen to 3,918 yuan. Wages for migrant workers in the construction sector were slightly higher than for those in manufacturing and low-end service jobs (see chart below) but the real picture starts to emerge when we compare the rate of increase in wages with the massive increase in profit accrued by the construction companies. While wages increased just five-fold in the 32 years from 1985 to 2017, profits in the construction industry increased by a staggering 119 times in just 24 years from 6.5 billion yuan in 1993 to 776.1 billion yuan in 2017.

In December 1978, China’s then new leader Deng Xiaoping first proposed the idea of moving away from egalitarianism and allowing some people (by dint of their work and enterprise) to get rich first. This idea soon became a fundamental principle of the reform and opening policy. It is clear from the construction industry however that in reality it was the bosses and business owners who got rich while the workers struggled just to get by.

In addition to low incomes, construction workers have consistently endured high rates of workplace accidents, injuries, deaths and occupational illness. The Ministry of Emergency Management noted in 2018 that, “for the last nine years, construction has been the industrial sector with the largest number of fatalities," and that in the first half of 2018 alone, the total number of workplace accidents in the Chinese construction industry reached 1,732, with 1,752 fatalities, a notable increase on the same period in 2017. Throughout the whole of 2018, the construction sector accounted for the largest proportion of workplace accidents (26 percent) recorded on CLB’s Work Accident Map.

The lack of workplace safety on construction sites has created a nightmare for workers and their families. In the event of an accident or occupational illness, construction workers struggle to get any compensation apart from basic hospital fees, and many never fully recover from their injuries, leaving their families impoverished.

Problems in the contracting system

One of the main reasons why China’s construction workers have to endure this dire situation is directly linked to the industry’s privatised and highly fragmented contracting system, which is riddled with corruption, the misappropriation of funds, and disruptions in capital flows. Each developer, lender and individual contractor is primarily concerned only with their own interests, leaving the workers on the construction site (at the very bottom of the sub-contractor hierarchy) in a very vulnerable position.

China has well-established laws and procedures regarding the financing, tendering and bidding process for construction projects but in reality, these have largely been bypassed or ignored. In particular, many projects are highly speculative and are undertaken without any real guarantee of funding. One of the most common practices in the industry is known as “capital contracting” (带资承包). This involves passing the financial risk of a project down the sub-contracting chain, so that in the end it is the lower-level contractors (including the labour contractors) who take on the biggest burden.

The authorities have long been aware of this practice and, as early as 1996, the Ministry of Construction, the State Planning Commission and the Ministry of Finance issued a joint-notice prohibiting this kind of risk diversification and demanding contractors provide proper financial guarantees. However, this directive was largely ignored at the local level and it has remained common practice for contractors, who have won a bid, to bring in specialist subcontractors, labour-subcontracting companies, or (individual) labour contractors it can rely on to provide the necessary funding for the project. These specialist subcontractors, will then demand wage guarantees from their subordinate labour contractors and construction workers who have come with them to the work site. Many of these end-of-chain labour contractors and even ordinary workers might have to take out loans for a payment up the chain just to secure the work. If the flow of capital dries up, labour contractors are left having to pay their workers’ living expenses out of their own pocket and even pay for building materials to ensure the project can move ahead.

Many labour contractors have to juggle oversight of multiple construction sites. Not only do they need to recruit, organise and manage teams of front-line construction workers, but, worse, have to secure advance funding to make up shortfalls owed to their private affiliates. All too often, labour contractors and construction workers do not get a cent when they settle accounts at year-end or project completion because of the failure of the main contractor to secure genuine funding.

In 2006, the Ministry of Construction, the National Development and Reform Commission, the Ministry of Finance and the People’s Bank of China promulgated the Notice Regarding Strict Prohibition of the Practice of Capital Contracting in Government-Invested Construction Projects. Under this measure, development and reform agencies at all levels must thoroughly review construction projects and may not approve any government-invested project in which the source of funding was not secured. It also required that competent construction industry authorities at every level rigorously review whether or not funding is fully in place when issuing construction permits, and in cases where provisions are lacking, withhold construction permits. It also required that banks and other financial institutions should specify in loan agreements that bank financing may not be used for capital contracting in government-invested projects, and that:

The competent authorities undertake a lawful investigation into any company discovered to be a general contractor in a government-invested project that has used the capital contracting method, or when the same method is used by specialist subcontractors or labour-supply subcontractors in taking on subcontracted specialist or labour recruitment work.

The aim of the Notice is very clear: setting standards starting with government projects, and aiming to broaden their application. But over the last decade, results have been far from satisfactory, as evidenced by the thousands of wage arrears cases we see every year in the construction industry. Legislators, administrators, judicial officials and media commentators have come up with numerous proposals and suggestions on how to tackle and ultimately resolve the problem of wage arrears in the construction industry, these include amending existing laws, increasing fines for violations of the law, and strengthening the oversight of local government. However, they all seem to have overlooked one important player: the construction workers’ unions.

China’s Trade Union Law clearly stipulates that:

The union shall coordinate labour relations and protect the rights and interests of workers at enterprises through a system of equal-footing negotiation and collective contracts. Article 6, Clause 2.

And the Trade Union Constitution (Article 28) stresses that grassroots unions need to

Help and guide workers in signing and implementing employment contracts with corporations and public institutions for administrative purposes, and represent workers in signing collective contracts or other specialised agreements with enterprises and public institutions for administrative purposes, and supervise enforcement.

There is clearly a tremendous opportunity for the trade union to play a key role in tackling wage arrears in the construction industry by negotiating collective contracts that specify wage rates and schedules for all workers, and by drawing up lists of contractors with a history of wage arrears and those with good records that would allow workers to opt for those employers who are more likely to pay in full and on time.

Wage arrears and an intervention from above

Around five o’clock in the afternoon of 24 October 2003, then-Premier Wen Jiabao was passing through the village of Longquan in Chongqing. A local resident named Xiong Deming told Wen that her construction worker husband was owed 2,300 yuan in unpaid wages. Wen immediately instructed local authorities to sort out wage arrears to local rural migrant workers. Six hours later, Xiong’s husband had his wages paid.

The following day, Wen remarked to his deputy Zeng Peiyan that settling the matter of unpaid wages for rural migrants should be a high priority for the government and suggested that the so-called Tianjin experience be used as a model for other local governments to follow. Zeng then reportedly told Minister of Construction Wang Guangtao that: “It is necessary to settle all outstanding wage claims of rural migrants before the Spring Festival.” Again, the Tianjin model was touted as the way forward.

The Tianjin model calls for:

- A system of monthly payment and seasonal settlement of wages for rural migrant workers.

- A formal ID system for all rural migrant workers on site and collective employment contracts tailored to workers’ needs. Attendance records form the basis for wage payment. The labour supply company must create a worker employment file and salary ledger, register temporary labour with the general contractor and appoint a work-team leader.

- A system of wage-payment guarantees for rural migrant workers. The amount paid into the contingency fund would be one million yuan for the main contractor and 300,000 yuan for other enterprises. If a construction enterprise fails to pay wages on time or refuses to make payment, money is taken directly from the contingency fund.

- An innovative and professional team leader management system that will replace the traditional labour contractor system.

The success or otherwise of this model depended entirely on the effectiveness of local government administrative measures and the willingness of construction companies to comply. Even in Tianjin however, things did not go as smoothly as the government hoped, as evidenced by the numerous construction worker wage arrears cases that have been reported in the city over the last decade. These cases (eight of which are highlighted in the original Chinese text) all illustrate the multiple and competing layers of subcontracting in the industry and the intense frustration that builds up when local government and judicial offices fail to ensure that workers are paid what they are owed. The only way for these workers to get their wages paid in the end was by taking direct collective action but that also ran the risk of police intervention or getting beaten by company thugs.

It is difficult to overstate the extent to which the Tianjin model, as promoted by Wen Jiabao, has been a failure. This failure was not just the fault of Tianjin authorities, rather it was due to the impression given by Wen’s personal intervention in helping a worker recover wage arrears that the government had the authority and ability to solve wage arrears on its own terms regardless of the legal merits of the case.

Wen’s intervention established a real-world model for government officials, encouraging them to abandon the bureaucratic approach and get closer to the people affected by these wage disputes. However, the job of China’s premier is not to personally handle wage arrears cases but to properly coordinate and mobilise resources on all fronts, including enterprises, trade unions, the government, the judiciary and the media, to foster the establishment of a feasible long-term response mechanism. In this way, the persistent issue of unpaid wage arrears could be dealt with step by step, and, more importantly, systematically eradicated.

Unfortunately, the effect of Wen’s intervention was the creation of the so-called “firefighting” approach to the settlement of wage-arrears, which has become the standard response of local governments, in particular at the end of each year when worker demands for settlement reaches a peak. Wen’s action encouraged local governments to enthusiastically launch grand arrears-settlement campaigns, using all kinds of approaches. Some local governments have even resorted to “mine-clearance” tactics to deal with unpaid wages. That is to say, when the media uncover a dispute, the local authorities scurry around taking remedial measures, but if the media do not blow the whistle, nothing is done even when the same thing crops up elsewhere. If the local authority acts selectively, then you might as well also say that it is selectively inactive. Local government officials give the impression of being busy fighting fires but they never really focus on preventive measures, on how to stop the fire starting in the first place. This is precisely the reason why wage-arrears disputes involving rural migrants form an “endless soap opera, with various local authorities taking centre stage at the end of nearly every year.”

Another problem stemming from the premier’s intervention is the idea that the best way for workers to resolve their wage arrears problem is through some kind of dramatic action, such as mass protests or threatening to jump from a building, that will attract the attention of officials.

Construction workers in Chongqing face off against police during a protest over wage arrears

There are only 24 hours in the day, and government officials only have eight hours of work time – if that. If they have to devote all their time to helping workers recover unpaid wages, the more important goal of creating a system that effectively eradicates wage arrears falls by the wayside. A particular problem is that the long-term benefits from the creation of a lasting mechanism to curb wage arrears are outweighed by the quick political kudos local government officials can garner from the “firefighting” approach. In other words, Wen’s intervention has sharpened the focus of labour administration and local government leaders on short-term results, which in turn has held back the establishment of mechanisms for lasting settlement of the unpaid wage issue.

Since Premier Wen’s 2003 intervention, the idea that wage arrears are merely the result of inadequate government supervision has become increasingly entrenched. As a result, each time a wage arrears dispute ends in tragedy, there is a flood of official Opinions, Emergency Notices, Notifications and Measures cajoling officials to learn lessons from the tragedy and improve their performance. But their tenor has changed from the early days. The wording “China’s construction sector has become a wage-arrears disaster zone,” has evolved into “China’s construction sector remains a wage-arrears disaster zone,” and then to “despite everything, the construction sector is still a wage-arrears disaster zone.” Apart from the annual “fire-fighting” settlements of disputes before the New Year, the overall situation has not really improved. Despite all the fiscal and administrative resources invested by authorities at all levels over many years, measures to clear up wage arrears in the construction industry have been a complete failure.

When wage arrears disputes break out, construction workers seeking redress become footballs kicked around by different interested parties. Individual labour contractors tell construction workers that the problem is that the higher-level labour contractor has not given them the money, and then refers everybody to the higher-level contractor. Sometimes, the labour contractor will go with the unpaid workers to press their demands. The higher-level contractor will then tell the labour contractor and his workers that the problem is at the next level up the chain of labour contractors, or that a labour-subcontracting company or a specialised subcontractor has not paid on time or in the full amount. Ultimately, the dispute will percolate up to the main contractor who will claim that there has been a funding shortfall and there is no money left. Sometimes during this process, the workers’ wage claims will be recognised (in theory) but other times they will be told by the different contractors up the chain: “You did not actually do any work for us, we don’t know who you are, and so why are you asking us for money?”

If the workers turn to the local labour bureau for help, the officials there will probably demand to see an employment contract, knowing full-well that the workers almost certainly do not have one. Ironically, the labour bureau is in fact responsible (under the Labour Contract Law) for ensuring that all workers do have an employment contract but in practice, when officials discover violations they just resort to bureaucratic evasions.

The reality is that the laws, regulations and orders issued from above are essentially useless on the ground and local officials are powerless to help workers resolve the wage-arrears issues that have persisted for such a long time in the construction sector in China.

Here we need to ask, apart from following the raft of ineffective documents put out by government authorities, what have China’s trade union officials actually done to help individual construction workers who are owed tens of thousands of yuan in wage arrears? Have they got out of their offices and gone out into the construction sites to organise workers into unions and advise them on signing employment contracts? Have they represented workers and helped them sign collective agreements with local construction enterprises based on collective bargaining?

Work-related injuries in the construction industry

In the mid-2010s, the national government in Beijing made a concerted effort to tackle the chronic lack of work-related injury insurance in the construction industry. (Work-related injury insurance is one of the five types of social insurance employers are legally required to provide for their employees – See China’s social security system for more details.) It quickly became clear however that construction companies were not listening to the government and that construction sites essentially remained a lawless zone.

In the four years between 2014 and 2018, no fewer than five official pronouncements on the issue were published by a total of nine government departments including the State Council. Despite this massive effort, progress was slow and the government recognised that: “More effort needs to be made to bring flexibly (informally) hired rural migrant workers at all kinds of construction sites into work-related injury insurance programs.”

The Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security estimated that 99.73 percent of all new construction projects in 2017 were covered by work-related injury insurance and that about 40 million rural migrant construction workers (out of a total of about 50 million) had insurance. It should be noted however that this improvement was partly due to the fact that employer contribution rates are comparatively low and, given the high rate of accidents on construction sites, it actually makes sense for employers to pay for work-related injury insurance.

However, this has thrown up an important question. Is it acceptable or realistic to continually rely on the intervention of the government (particularly the State Council) to improve the work-related injury insurance system and make it work properly? Are the benefits of such official interventions sustainable? Are there any other resources that can be used in addition to administrative authority? Are there resources outside official government authority that have not been brought effectively to bear?

Here, we would raise again the important role that is so often overlooked: that of the construction industry unions. Imagine if construction industry unions could get tough and represent construction workers in closely monitoring implementation of work-related injury insurance programs. Imagine if unions could organise members at every building site into a boycott campaign in which workers would refuse to enter any worksite that does not provide work-related injury insurance for all workers. Without doubt, if this could be achieved, the level of insurance coverage at individual worksites and in the construction industry as a whole would rise, and the benefits would be sustainable.

Construction workers and rescue workers race to find colleagues trapped in a building collapse

So, what happens when workers in China’s most dangerous profession do get injured or even killed at work. There are detailed provisions on the procedures that should be followed in the event of a work accident in the 2004 Work-related Injury Insurance Regulations and the 2011 Social Insurance Law etc. These provisions should ensure all injured workers are adequately compensated. What actually happens however, as CLB has noted in several previous research reports on work safety in China, is very different.

The key problem is that verification and assessment of work-related injuries is a very complicated and time-consuming process, especially if workers do not have a formal employment contract that can specify exactly who their employer was at the time of the accident. The Beijing-based non-governmental organization, Ren Jian New Workers (北京行在人间文化发展中心), published a report in 2015 which showed that, of the 73 work-related injury cases involving construction workers that were taken up by the group between 2010 and 2014, 89.1 percent of workers had not signed any contract and did not have work-related injury insurance, and in 60.2 percent of cases, it was ultimately difficult to verify any employment relationship. Of these workers, 89 percent had compensation claims rejected, and “there were even some cases of large state-owned enterprises saying that they had no money, leaving the courts unable to take any action.” Faced with this situation, injured workers generally chose to scale back their demands and seek a private settlement. Even the injured workers who opted for litigation and were lucky enough to stay the course and win still often went away disappointed: 21.9 percent struggled to get the court rulings implemented.

The Social Security Law created a system of advance payments from the work-related injury insurance fund designed to protect workers from delinquent employers who did not provide insurance and refused to pay compensation after an accident. But in the more than eight years since its appearance, this arrangement is still encountering severe problems in practice. Some legal experts have already called the provision a dead letter. There have been very few successful instances of workers applying for advance payments and the rare success stories were all the result of forceful intervention by the courts. If local social security offices collude with the courts however, and come up with pretexts to justify inaction, the enforcement of the advance payment mechanism will fade away.

As a consequence of this fiasco, construction companies are actually encouraged to gamble with safety risks. When insurance contributions are not paid, and, worse, investments in improving workplace safety are not made, the health and even lives of construction workers are continually exposed to risk, and the industry will remain the employment sector with the highest accident and death rates of any in China.

Once again, we have to ask, what is the trade union doing about this issue. Back in 2014, the former ACFTU secretariat chairman, Li Binsheng, proposed “a practical solution to the issue of safeguarding of the rights of employees injured at work.” His idea was that government authorities, industry associations and construction companies should be at the core of “a multi-layered training system for construction workers, and raise standards of safety awareness and technical skill in construction roles and jobs, while reducing accidents.” With regard to the role that the trade unions can play in protecting the rights of construction workers, all Li could come up with is that unions should “do more to expand legal assistance.”

In response, we cannot stress enough the fact that trade unions are not legal aid organisations. The duty of the unions should be to organise workers at building sites, and their role should be to represent them in fighting to improve working conditions and benefits, and represent workers in defending their rights and interests after an accident.

When an injury, illness or even fatality results from a work accident, unions should immediately enter the site and, in their capacity as representatives of the construction workers involved, demand that the company submits an application for verification of occupational injury within 30 days, as provided by Clause 1 of Article 17 of the Work-related Injury Insurance Regulations. If the company refuses to submit such application, the union should, submit to local social security authorities the application for verification in the name of the injured worker(s), pursuant to Clause 2 of Article 17 of the Work-related Injury Insurance Regulations. After injury verification, the union should represent the worker(s) involved in discussing and negotiating due benefits and compensation with the construction company involved. If the company refuses to provide the legally mandated benefits and compensation, the union should represent the workers in submitting an application for advance compensation payment from the work-related injury insurance fund.

If construction industry unions can get truly engaged and make full use of the powers already vested in them by the Work-related Injury Insurance Regulations, then the problem of getting due compensation paid after a work accident could certainly be alleviated.

Getting to the root of the problem

Extra-legal practices of all kinds, affecting labour relations, operating conventions, wage payments, workplace safety and other areas, have dogged the construction industry in China for many years. Yet there is a fundamental problem that allows construction companies to sidestep the Labour Law, the Labour Contract Law, the Work-related Injury Insurance Regulations, the Social Insurance Law and the Production Safety Law: namely, excessive faith in amendments to the law and an excessive dependence on government authority for legal enforcement. On the other hand, the potentially positive role of the construction workers themselves and the role of construction industry unions has been completely overlooked.

As we have seen above, there is no shortage of laws and regulations governing and constraining the construction industry in China. Neither is there any lack of management measures, Opinions, Notices, Urgent Notices etc. issued by the State Council, local governments and other administrative agencies. However, just about all of these legislative and administrative documents are ignored on the ground. This is primarily because the process of drafting labour legislation in China is more like an exercise in academic theorising than a genuine debate between labour, management, the government and other concerned parties. This is why shiny new labour laws in China may look impressive on paper but have proved less effective than just about any other kind of legislation. And in some cases, the laws have actually harmed the interests of the workers they were designed to protect.

Let us take, for example, the highly controversial Article 14 of the Labour Contract Law. This Article, which basically says employees are entitled to an open-ended employment contract after ten years of continuous employment, was an attempt by legislators in Beijing to maintain some of the old state-planning era employment guarantees in the new market-orientated economy that emerged in the 2000s but it backfired spectacularly.

In the time between the passage of the bill on 29 June, 2007 and the law’s enactment on 1 January, 2008, the majority of enterprises (including large and state-owned enterprises) scrambled to slash their workforces. At the end of June 2007, the China unit of LG Electronics, for example, culled large numbers of veteran employees at its headquarters and at branches all over the country, including up to 20 percent of employees in its unit in the Chengdu area that had just been devastated by a massive earthquake. At the end of September, tech giant Huawei required more than 7,000 workers who had completed at least eight years of service to submit “voluntary” resignations to the company. These workers had to “voluntarily” quit before January 2008, and then compete to get their old jobs back again. The new contracts they then signed with the company were for one to three years at most.

Not only did the Labour Contract Law trigger a wave of redundancies even before its enactment, other articles and clauses supposedly protecting workers interests in the areas of temporary agency work, collective contracts and part-time work, all proved to be ineffective. To date, large numbers of workers in the construction industry in China have yet to sign employment contracts. According to Li Xiang, a lawyer at the workers’ legal aid office of the Xuhui District Federation of Trade Unions in Shanghai:

During consultations, one thing I noticed that was pretty much universal was that work units do not sign employment contracts with employees; and if a contract has been signed, the employer refuses on some pretext or other to allow the employee to retain the text.

If this is the situation in a major city like Shanghai, we can safely assume the situation is even worse in smaller cities and rural areas.

The Labour Contract Law was amended in 2013 in an attempt to prevent the widespread abuse of the labour agency system. Yet, by 2015, industry experts noted “the problem of illegal deployment of temporary agency staff has continued to crop up at state-owned enterprises” and “the use of temporary agency staff is gradually becoming a cause of frequent labour disputes.”

Legislators and senior government officials have proposed amending the law again to allow for more flexible hiring practices, while other critics of the law argued that tougher clauses were needed to curb the illegal behaviour by companies and protect workers’ rights and interests. Clearly, different interest groups are unhappy with the law but amending it again is not the answer.

On 20 March, 2018, Beijing No. 1 Intermediate People’s Court vice-president Sun Guoming noted that:

As things stand, labour legislation is not able to fully meet the practical needs of court proceedings. Provisions in the Labour Law are overly principle-based, there are too few supporting laws and regulations, and applicability needs to be improved; bureaucratic rules and local laws are legislatively primitive, authorities are insufficiently centralised, and systems do not function properly. Given the lack of sound legislation to follow, the question of whether it is possible to invoke general civil laws and regulations for settlement of labour disputes, combined with the fact that many labour disputes, particularly those concerning social insurance, are subject to administrative law and bureaucratic rules, challenges have arisen in the application of law in current labour dispute proceedings.

Sun noted that his court often had to deal with multiple individual cases stemming from the same collective labour dispute. In order to relieve the burden on the courts and better deal with the issues at the heart of the dispute, Sun suggested that employers should “engage in negotiations with workers or union representatives as equals.” He also suggested that:

Workers should join the trade union, better understand legal provisions, have reasonable foreknowledge of their rights and interests, be fully aware of litigation risk, and, in cases where rights and interests are violated, pursue settlement first through negotiation and mediation.

Rather than continue to amend the law or seek once again to improve enforcement, Sun sought to transcend the issue by emphasising the importance of the trade union in good-faith bargaining between labour and management.

Sun’s analysis shows us that the government cannot make labour dispute mediation more effective by bringing to bear external or higher authority, and likewise, court rulings lack the judicial power to foster better mediation. In other words, the all-pervading public authority exercised by the government and the courts in the time of the planned economy has dwindled to a shadow of itself in the market economy.

In order to resolve the fundamental issues that lead to worker exploitation in the construction industry, it is necessary to dispel this blind faith in public authority and gradually develop an institutionalised bargaining mechanism in which negotiations between equal partners - labour (as represented by the union) and management (represented by federations of construction companies) – can foster harmonious coexistence in labour relations in the construction industry.

Here we can look at the construction industry in Denmark for an example of how this has worked in practice. Compared with other European states, Denmark actually has very liberal provisions for terminating employment contracts. If the employer terminates an employee within 12 months of taking him or her on, they do not have to pay any severance or compensation. Moreover, except in the case of large-scale layoffs or where specific alternative provisions exist in a collective agreement between labour and management, employers do not even have to consult the unions when laying off staff. Even after negotiations take place, the results do not necessarily affect the right of the employer to lay workers off.

However, this arrangement depends wholly on Denmark’s comprehensive system of social security, especially with regard to unemployment benefits, which ensure workers can maintain a decent living even if they are laid off.

Who proposed this social security system? Who designed it? Which social security research body did the investigative groundwork? The answer is nobody.

Denmark’s flexible employment system and the social security safeguards that it depends on go back over 100 years. This win-win model of coexistence between labour and management was gradually developed by individual companies and industry federations working together with the country’s trade unions, on the basis of annual collective bargaining. It has only been possible to develop this system through a constant cycle of repeated contention and compromise over the years and decades between unions and employers within this framework of institutionalised collective bargaining.

Promises of a bright future mask the troubled reality of the construction industry. Street scene in Daxing, southern Beijing.

Conclusion

Issues such as wage arrears, failure to sign employment contracts, low rates of work-related injury insurance coverage, and poor workplace safety have plagued the construction sector in China for many years. However, this is not due to the unscrupulousness of construction bosses or the failure of apathetic government officials to do their jobs. Much less is it due to a lack of rights awareness among construction workers. Rather it is to a large extent caused by the absence of an effective trade union that can promote and defend workers’ interests.

For this situation to change, the union must first eschew its traditional role as a neutral mediator and facilitator between labour, management and government, and reclaim its identity as the sole representative of the interests of the construction workers, and become one of the central actors in the development of labour relations in China. The union must stop being a rights advocate that only provides legal assistance after workers’ rights have been violated, and focus on organizing and representing workers in collective bargaining with construction industry federations.

Of course, if the union does get back to basics in this way, it will not remove at a stroke all the ills that have afflicted the construction industry in China for so long. It will only be the starting point in the search for a way out.

In 2018, the construction industry began using a real name registration system that could, if managed properly, assist the union in getting back to business. The union could create its own platform for real-name registration for union members. Such a platform should include information on specific contractors and information on workers with particular job skills. The platform could then serve as a hub, matching construction enterprises all over China with construction workers with different skills. This would lead gradually to the union assuming a leadership role in hiring and employment in the industry.

Construction industry unions should establish channels of communication with national and regional construction industry federations all over China, and discuss the feasibility of creating annual collective bargaining mechanisms for the sector. They should also set up training centres for construction industry workers in different regions, focusing on safety awareness training and appraisal, with professional skills training and grading of performance for specific trades. Construction workers who have undergone union-organised workplace safety training and performance evaluation would not need further training by their employer and could be hired directly from the union’s real-name registration platform. Finally, and most importantly, construction industry unions should require their staff to get out of their offices and go into building sites to drum up membership.

Over time, the unions could expand membership and build up trust among construction workers so that they are seen by everyone as a representative of labour. In the end, this will enable the union to represent construction workers in all regions in collective bargaining with federations of construction companies. With a collective bargaining system in place in the construction industry, it would gradually become possible to resolve issues such as wage arrears, lack of employment contracts and social insurance, and inadequate workplace safety.

For a PDF version of this report, please click here.