- Dongguan Gogo Garment Manufacturing Ltd. is the largest undergarment factory in Dongguan, China’s manufacturing hub, and it supplies high-end brands in Europe and the Americas.

- The reputable factory was reported to have paid decent wages and been stable employment for decades before recently owing workers wages and social insurance. But now the owners have no funds to compensate workers in light of the sudden layoffs.

- The factory’s closure calls into question global supply chain practices and brand responsibility since the start of the pandemic.

Workers at the largest undergarment factory in Dongguan, Guangdong province, began protesting on 5 January over owed wages and social insurance. On 10 January, the factory abruptly announced the closure of its business. Management told the more than 1,700 factory workers to leave the Gogo factory campus with their belongings within a week’s time. On 14 January, workers again marched in the streets to demand compensation.

In its official notice, the Dongguan Gogo Garment Manufacturing Ltd. cites operating problems, including shrinking customer orders and “internal and external environmental factors.” The company noted that it has been in difficulty for some time and tried to avoid this outcome. When customer orders began to decline, it took cost-saving measures and tried to develop the domestic sales market, to no avail.

The city of Dongguan is China’s manufacturing hub, although over 3,000 factories are reported to have closed in the first half of 2022 alone. The longer-term trend is that manufacturing has been moving out of China, and this has been recently exacerbated by the pandemic and other factors.

Gogo has been around since the 1980s, and since 2011 is a wholly-owned subsidiary of Hong Kong’s Clover Group International Ltd. (Gaohua). Gogo is Dongguan’s largest overseas-funded garment factory. About 80 percent of the workers are women. The factory produces or has produced high-end undergarments for brands in the European and American markets, including for Victoria’s Secret, Under Armour and Lululemon at the time of its closure, and for GAP, Marks & Spencer and Lane Bryant in the past.

Photograph: humphery / Shutterstock.com

Workers take collective action to demand wages, benefits, and severance pay

On 6 January, community members spotted a large number of factory workers walking in the area of the Gogo garment factory, conjecturing that they were seeking exercise to boost their immunity to Covid-19. It is now understood that their activity was related to their demand for wages and social insurance, and workers were again seen marching after nightfall.

After the announced closure, workers protested again on 14 January and demanded layoff compensation. On 20 January, a worker reported that discussions with management and the local government have been ongoing, and workers were given a very small amount of compensation. The worker said, "This really made all the employees bitterly disappointed."

The Hong Kong owners are reported to have typically followed labour laws and regulations, including a leave system and paying all mandatory insurances and housing fund allowance.

Under the Labour Contract Law, for mass layoffs or business closure, employees are legally entitled to severance pay according to the number of years worked at the factory (Arts. 46-47), notice of 30 days’ must be given (Art. 41), and the employer must hold consultations with workers or the trade union as well as make a report regarding the layoffs to the labour department (Art. 41).

The Gogo factory’s 10 January notice of the shutdown does not meet the 30 days’ notice requirement, and workers’ protests indicate that wages, benefits, and severance pay at this time are not in compliance with the law.

Someone who lives in the neighbourhood spoke to the media about the formerly stable pay and working conditions at the Gogo factory:

This is a good factory. This is the factory with the highest wages in Dongguan. Employees here are given a small gold medal after they have served for 15 years.

The neighbour said that most of the workers started when they were young but now are middle-aged, and most come from Guangxi province. Front-line piecework employees are paid about 8,000 yuan per month, and they get four days off per month.

A former Gogo worker said:

I spent ten years of my youth here. Although it has been many years, I can still clearly remember every corner of this place in my mind. Now that the factory is closed, it is so sad!

The factory’s closure raises questions about how workers’ interests can best be protected during difficult economic times, and whether worker organising and collective bargaining mechanisms prior to the closure would have brought a more favourable result. In addition, global supply chains are dictated by the brands at the top; how could a more equitable system prioritise the interests of suppliers and their workers at the bottom of the chain?

Manufacturing industry was once a stable form of employment; broad trend is toward precarious work

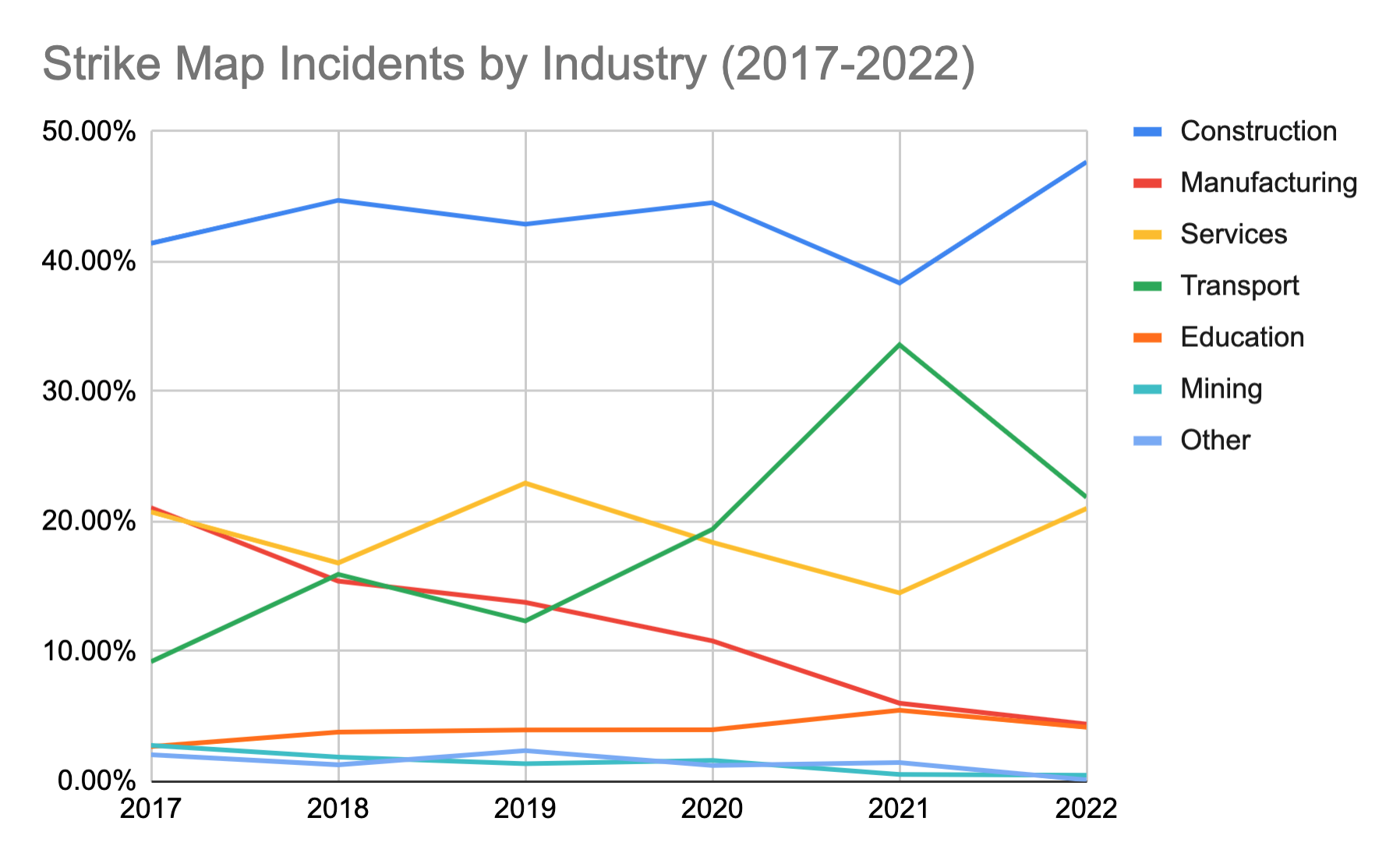

On the whole, the number of protests by manufacturing workers in China is small, with only 37 recorded in CLB’s Strike Map in 2022. The proportion of incidents collected in the industry has dropped from about 20 percent of total collected in 2017 to less than 5 percent in 2022. However, some incidents are recently trending larger-scale, with hundreds or thousands of workers participating at a time. For example, there was the series of events at Foxconn in Zhengzhou during peak iPhone production in late 2022; and the layoffs of temporary contract workers at medical supply companies after China’s pandemic policy reversal brought out large numbers of workers in Chongqing and Hangzhou.

The closure of Gogo is different in that its end has been a long time coming and should have been foreseeable and perhaps avoidable, but for global supply chain practices in which brands determine purchase prices and have the liberty to decrease their orders without concern for the effects on suppliers and workers.

In 2020, with temporary and permanent factory shutdowns and changing patterns of migrant worker labour as a result of the pandemic, many workers have been pushed into less stable forms of employment, such as in the services sector and gig economy. The sustainability of these labour models, particularly as China is trying to increase its domestic consumption and decrease economic inequality, is potentially low.

As China’s manufacturing industry has seen a decline in recent years, this once-stable form of employment may become part of a bygone era. Workers of all kinds need strong representation for their labour rights, and local authorities should help find a way for companies’ layoffs to comply with China’s labour laws.

Further CLB reading:

- China Labour Bulletin Strike Map data analysis: 2022 year in review for workers' rights (January 2023)

- What You Need to Know about Workers in China: Employment and wages (last updated September 2020)

- CLB topic page: Factory workers