Analysis of CLB’s labour data collected in 2022 shows it was a difficult year for workers in China, and 2023 is already gearing up for intensifying labour conflicts if workers continue to go without representation.

In 2022, China’s workers faced pandemic restrictions, regional lockdowns, and an economy that contributed to labour rights struggles. CLB broadly analyses the raw data collected in our Strike Map and conducts sector-by-sector analysis of issues affecting China’s workers and their labour rights:

- China’s property market woes led to residential development and infrastructure projects moving to China’s smaller cities and bringing labour rights challenges with them;

- The services sector and logistics industry saw the greatest rise in strikes and protests year-on-year, reflecting the growth in these sectors, the effects of the pandemic, and the new challenges of the gig economy;

- The number of protests in the manufacturing industry declined, but the scale of some protests grew;

- China’s workers urgently need adequate representation for their pressing labour rights grievances, and CLB calls on the ACFTU to improve its record.

Table of Contents

I. Broad trends

II. Sectoral analysis

A. Construction

B. Services

C. Retail

D. Transport and logistics

E. Manufacturing

III. Conclusion

I. Broad trends: Greater use of official channels, lesser likelihood for workers to resort to collective actions

The total number of incidents collected by the CLB Strike Map in 2022 was 814, about the same volume as during the first year of the pandemic in 2020, and about 25 percent fewer than the 1,095 incidents recorded in 2021. In 2022, over 87 percent of the incidents were over unpaid wages.

For reference, CLB’s Workers’ Calls-for-Help Map, which was launched in October 2020, has collected an increasing number of incidents, from 1,118 in 2021 to 2,232 in 2022. Of course, our maps can only gather a small percentage of total incidents that occur and are limited by various factors relevant to our methodology, but we can infer from the data in these two maps that in the context of deteriorating economic and labour conditions, workers are less likely to resort to collective actions like strikes and protests and may individually seek help from official channels, including taking their pleas online for attention toward resolution. Some additional factors are that when workers face labour rights challenges, their priority is to immediately find new sources of income rather than pursue their rightful claims that take time and effort - and that may incur high risks for actions such as publicly protesting.

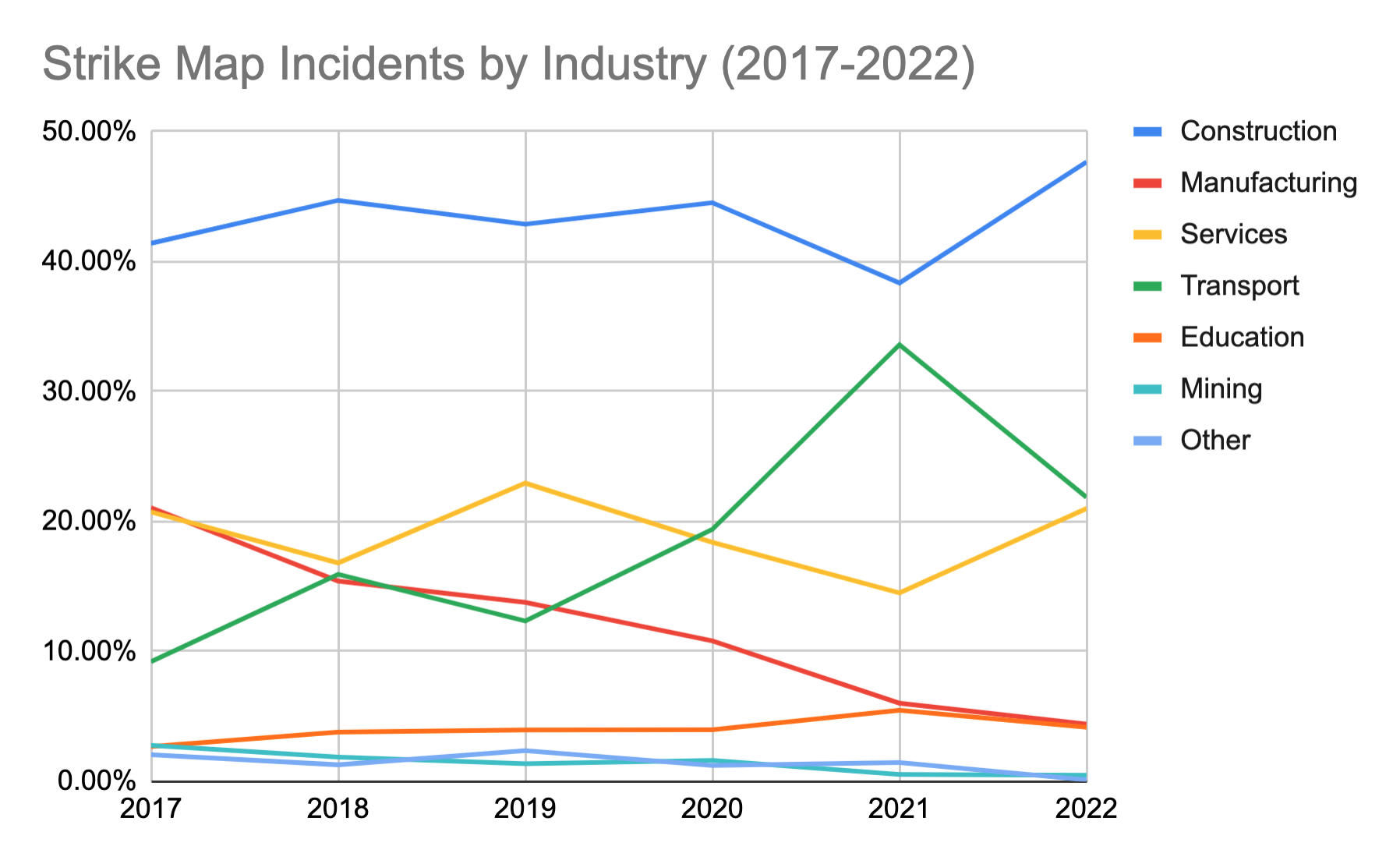

Although the total number of incidents collected in the Strike Map decreased in 2022, the industry distribution of the incidents is in line with the proportions and trends seen over the past few years. In 2022, the construction industry again led with the most collective actions by workers (48 percent), followed by transportation (22 percent), services (21 percent), manufacturing (4 percent), education (4 percent) and mining (0.5 percent).

Over the past five years of Strike Map data, a few trends are worth noting. The proportion of incidents in the construction industry has remained steadily above 40 percent, other than a slight drop in 2021. The country’s debt crisis, expansion of the real estate industry, and property market free fall have increased the incidence of protests for unpaid wages, especially in light of corporate bankruptcy. Incidents in the transport industry have risen as the services and logistics industries have thrived, accompanied by rising dissatisfaction about working conditions. China’s manufacturing industry has been transitioning to high-tech production, and the decline in incidents has been correspondingly swift and steady. The country’s transition to renewable energy sources is also evident in our low levels of data collected in the mining industry (but see our Workplace Accident Map for health and safety issues in mining and other industries).

II. On the ground: Sectoral analysis of labour data

A. Construction workers go unpaid as real estate companies relocate to second- and third-tier cities, bringing economic problems to inland provinces

Among the protests by construction workers in 2022 (399 incidents), those related to residential construction account for 40 percent (158 incidents). These protests involve many large, private companies, such as Greenland Group, Country Garden and Sunac Group. Regionally, the highest concentration of construction-related protests occurred in China’s northern provinces of Shaanxi, Shandong, and Henan; followed by Jiangsu and Guangdong.

This reflects that most of the protests in the construction industry are related to the expansion of real estate companies and related infrastructure projects to second- and third-tier cities in recent years. As the competition in the real estate market in China’s first-tier, coastal cities decreases, many real estate companies have turned to development in inland cities, which brings the problems of corporate debt and workers’ wage arrears to these regions.

CLB Strike Map: Geographic Disbursement of Construction Industry Incidents (2022)

In the construction industry, protests for unpaid wages can be large-scale and intense, and they reveal the depths of the property market woes. For example, on 28 January 2022, more than 100 workers went to the Chongqing Jinke headquarters to demand their wages. During the process, workers rushed the office building and smashed items in the office lobby.

According to online news reports, Jinke’s business was struggling at the beginning of the year, and in order to get rid of housing stock, the company asked its employees to buy property at a 3.3 percent discount. Management personnel were essentially forced to purchase the company’s properties. On top of that, the employees were required to utilise the company’s wealth management products to come up with the funds. After the workers staged their protest, the company held consultations and promised to pay workers their wages.

B. Pandemic conditions led to protests by medical workers, sanitation workers, others in service sector

In 2022, there was a rise in worker protests in China’s service sector, specifically in the medical industry, sanitation, and retail.

Out of 173 incidents in the service sector in 2022, 29 were at medical facilities. These medical industry protests were related to the management of hospitals during the pandemic (10 incidents), as well as a shortage of funds in some hospitals that led to wage arrears (19 incidents).

The pandemic led to a labour shortage in hospitals, with medical staff working overtime for extended periods, and medical students being required to fill in without adequate compensation or labour guarantees. In many cases, management could not arrange for adequate staffing, so medical workers who contracted the virus were required to continue to take care of patients and work in the quarantined sections of the facilities. This led to an increase in the spread of the virus, exacerbating the supply and demand imbalance and leading to a vicious cycle.

The protests against wage arrears at hospitals largely took place in secondary and tertiary hospitals in Shaanxi and Liaoning provinces, and most of them were at private hospitals. As CLB published in September 2022, systemic industry problems have been highlighted by the strain of the pandemic, notably financial allocations and government subsidies that lead to low pay and poor working conditions in the industry. Meanwhile, the increase in the workload from the pandemic has greatly increased hospitals’ expenditures on protective equipment and other consumables, causing many public hospitals to encounter financial difficulties. Yu Xiaobao, vice president of the Private Hospital Management Branch of the Chinese Hospital Association, said in May 2022 that more than 2,000 private hospitals have gone bankrupt since 2020.

China’s sanitation workers also face wage arrears as frontline pandemic workers. The public revenues of some provinces and cities have been strained due to the economic recession and stagnation of the real estate market. This has led to problems in the operation of municipal services, including sanitation work. On 23 June 2022, hundreds of sanitation workers in Hohhot, Inner Mongolia, gathered to protest against wage arrears from a state-owned enterprise, the Ruyi Development Zone Public Utilities Company. In an interview with reporters, staff noted that the company had financial problems, leading to difficulties in paying wages. The situation had lasted for two or three months by the time they spoke out, and the workers urged the company to pay them, also placing responsibility on the local government to come up with the funds.

C. Traditional retail models decline and established brands go bankrupt, leaving workers in the lurch

In 2022, retail industry protests revolved around the transformation of industry models toward online consumption. One type of situation giving rise to worker protests is when a business expands or innovates and then closes its new ventures. Hema Fresh Foods stores in Beijing and Xi’an faced this problem, and so did Suning Carrefour in Hefei and Chengdu. Hema is an Alibaba grocery concept store that involves memberships, group buying, online ordering and delivery, and physical stores. China’s domestic appliance retailer Suning purchased an 80 percent stake in French retailer Carrefour’s China’s operations in 2019 and has since closed many of the stores. At Hema and Carrefour in 2022, workers protested unpaid wages and demanded economic compensation in layoff packages, respectively.

Another situation is that traditional retailers have been pushed out of the market by online models and are facing bankruptcy. Domestic casual clothing retailer Metersbonwe, which was established in 1995 and rose to the height of its popularity in the late 2000s, has begun layoffs and asset sales as the result of continuous business losses. Online fast fashion business models have rendered traditional models and mass-produced styles outdated. At Metersbonwe’s Chongqing store, half of the employees were illegally dismissed in June 2022 and wages were not paid. Workers instigated labour arbitration over their wage arrears.

A large, domestic electronics retailer, Gome, also saw workers protest over unpaid wages. The traditional retailer has faced competition from online retailers such as JD.com, Suning, and Tmall, shrinking Gome’s market share to about 5 percent. On 6 December and 8 December 2022, workers protested unpaid wages at Gome, and physical conflicts arose during meetings with the company’s management.

D. Growing gig economy and express price wars; lack of labour protections for platform transport workers in shrinking ride-hailing market

Protests in the transport and logistics industry were focused on express delivery and online ride-hailing. Out of 392 incidents in the industry in 2022, 72 involved couriers in the express delivery sector and 87 for workers for taxi and ride apps.

The express delivery industry in China has engaged in fierce price wars during the pandemic to compete for market share. The unit price per delivery has declined since 2021, and companies have responded by controlling operating costs and improving their ability to expand their markets. China’s main express delivery competitors are YTO (16 percent market share), Yunda (15.5 percent), STO (13 percent), SF (10 percent), and ZTO, with a new 2022 competitor, Jitu Express. In the current price war, Yunda and STO are at a disadvantage. Yunda competes through the price-for-volume method, but the company’s expense ratio is the highest among competitors, leading to outlet management conflicts. STO fell into a loss in 2020 and has not been able to return to profitability.

The number of courier strikes and protests logged in 2022 correspond to the market conditions: Yunda saw 19 incidents after outlet closures and workers sought wages; STO and ZTO had 14 incidents each; and YTO saw 9 incidents of worker strikes and protests.

Another pattern is that platform drivers going longer distances have been shorted income through changing algorithms and pricing models. In the case of Huolala, a domestic platform transport company, this pricing model change led to strikes across China from 16-18 November 2022. Workers protested high commission rates of the platform, and how “multi-factor” orders calculated pay rates for variable conditions. Drivers in Shenzhen, Dongguan, and Foshan came out en masse at the Huolala offices, and drivers in Wuhan, Changsha, Quanzhou, Wenzhou, and Zhengzhou also staged actions in response.

Compared with the express delivery industry and increased demand during the pandemic, city lockdowns and changing patterns of citizens’ movement habits have affected the taxi and ride-hailing industry. The number of trips has dropped significantly, reducing demand for these services. For years, taxi drivers have protested against car rental fees and other cuts from their rates, and in 2022 ride-hailing drivers likewise joined in protests requesting to return their vehicles that they leased from the platform companies. T3 Mobility is one example. T3 Mobility is a more recent ride-hailing competitor of Didi. From February to September 2022, the company’s drivers in Suzhou, Hangzhou, Chengdu, and Zhuhai all went on strike and demanded they be able to return their cars. On 21 February 2022, hundreds of T3 drivers gathered in Suzhou. One driver who participated noted that his daily income is only about 100 yuan, which is not enough to pay the leasing fee on the vehicle to T3.

E. Manufacturing industry decline is apparent in electronics, garment and apparel, and housewares sectors; although rate of protests has dropped, scale of protests may increase

Two large-scale protests in the manufacturing industry last year occurred at Quanta Computer in Shanghai, and at Apple’s major iPhone supplier, Foxconn in Zhengzhou, Henan province. In each of these incidents, workers were dissatisfied with pandemic prevention arrangements within their locked-down factories.

Other collective worker actions have been linked to the downturn in manufacturing. In September and October of 2022, the decline of the electronics, toy, and clothing industries attracted media attention. The China and Foreign Toys Network reported that five traditional toy companies showed a loss in net profits last year. Due to the unsatisfactory performance of the iPhone 14 market, Zhengzhou Foxconn has dismantled or will dismantle at least five production lines. Times Online pointed out that during what is normally peak season, there was no need for workers to work overtime and they left on time each work day. The factories in Guangzhou’s garment village have been producing intermittently or even shutting down altogether, which has affected the income of workers. At present, the average monthly salary is only one-third or one-half of their previous income.

On the whole, the number of protests by manufacturing workers is small, with only 37 recorded in our Strike Map in 2022. This low number may be related to the delay in paying wages in the face of slumping demand in some companies, and it is difficult for workers to spend time fighting with their bosses instead of immediately finding alternate sources of income. One difference from labour challenges in the express delivery and retail industries is that although these types of companies are facing bankruptcy, manufacturing workers lack recourse from higher levels of corporate structures. With express delivery and retail, giant corporations are at the end of the line, whereas many manufacturers are small-scale. These small companies are prone to cash flow issues and less liquid assets, and bosses have been able to transfer assets out of the company to avoid responsibility. Even if workers win their arbitration cases, there will be no assets with which to pay out the award.

For example, in September 2022, a housewares factory in Foshan, Guangdong province, was in arrears with its workers for three months. The industry has been in decline for years, and many manufacturers face bankruptcy. On 11 September, a worker climbed onto the factory roof and threatened to jump, after the boss refused several times to pay wages. In the end, the worker was rescued, but the payment of wages remains unresolved.

III. On verge of global recession, China’s workers need adequate representation

In the first days of the 2023 new year, the International Monetary Fund’s managing director, Kristalina Georgieva, stated that one-third of the world's countries will fall into recession in 2023. She also noted that, “For the first time in 40 years, China’s growth in 2022 is likely to be at or below global growth.” This is in the context of the U.S., Europe, and China all facing economic difficulties, with a fall-on effect for the rest of the world.

Based on our observations in 2022, the business closures and market reshuffling within various industries in China will likely become more intense in 2023. Real estate companies, brick-and-mortar retailers, and factories that mainly sell to foreign markets will all face greater pressure. At the same time, up-and-coming companies will further expand their market shares through acquisitions and asset purchases and may eliminate struggling giants. Whether China's official channels can effectively handle the labour conflicts between workers and enterprises under the increasing layoffs and wage arrears will be telling for the levels of unrest on the ground in the coming years.

China’s workers have a pressing need for better representation of their interests before enterprises, local governments, and within the justice system. Without adequate representation for even the most basic of needs such as being paid in full and on time, labour crises like those at Foxconn, and more recently at a Covid-19 medical supplier in Chongqing, will certainly escalate in the near future.

In our investigations of the role and effectiveness of China’s official trade union in incidents both large and small, we consistently see the union’s own ignorance of the conditions of workers on the ground. China Labour Bulletin calls on the All-China Federation of Trade Unions to take pause and anticipate the needs of China’s workers in various industries, and to actively intervene in disputes caused by wage arrears, layoffs, and other fundamental challenges. The union should understand workers’ demands, negotiate with enterprises on behalf of workers, and involve other stakeholders such as government actors in speedy and just resolution.