For the Chinese version of this article please see 农民工及其子女 on our Chinese website.

The 2022 official estimate of the population of rural migrant workers in China is 295.62 million, comprising more than one-third of the entire working population. Migrant workers have been the engine of China’s spectacular economic growth over the last three decades, but they remain marginalized and subject to institutionalized discrimination. Their children have limited access to education and healthcare and can be separated from their parents for years on end.

Definition

Rural migrant workers (农民工) are workers with a rural household registration who are employed in an urban workplace and reside in an urban area. They are not necessarily from rural areas. Many grew up or were even born in the city. They consider the city to be home, but—because of the inflexibility of the household registration system—tthey are unable to obtain urban residency and remain classified as rural migrants.

Background

Household registers have been used by the Chinese authorities for millennia to manage taxation and control migration. The current household registration (hukou 户口) system was formally introduced by the Communist government in 1958 and was designed to facilitate three main programs: government welfare and resource distribution, internal migration control, and criminal surveillance. Each town and city issued its own domestic passport or hukou, which gave residents access to social welfare services in that jurisdiction. Individuals were broadly categorised as "rural" or "urban" based on their place of residence. Moreover, the hukou was hereditary so children whose parents held a rural hukou would also have a rural hukou no matter where they are actually born.

The hukou system was supposed to ensure that China’s rural population stayed in the countryside and continued to provide the food and other resources that urban residents needed. However, as the economic reforms of the 1980s gained pace, what the cities needed most was cheap labour. And so began what is often described as one of the greatest human migrations of all time, as hundreds of millions of young men and women from the countryside poured into the factories and construction sites of China’s coastal boom towns. In many cities, such as Shenzhen and Dongguan, the population of migrant workers quickly overtook that of the local urban population.

As migrant workers poured into the cities, it became clear that hukou restrictions on internal migration were not only unenforceable but also counter-productive to social and economic development. But it was only in 2003, after the tragic death in police custody of a young migrant worker named Sun Zhigang that the barriers to migration started to come down. Sun had been detained by police in Guangzhou simply because he did not have a temporary resident permit as required by law. The public outcry at Sun’s death led to the abolition of many of the most egregious restrictions on the freedom of movement in place at the time. In many smaller cities, hukou restrictions have gradually been dismantled, but the system itself is still very much in place. Indeed, as the urban population continues to grow, the authorities in major cities such as Beijing are now actually making it more difficult for migrant workers and their families to access social services (see discussion on urbanization and hukou reform below).

As China’s demographics change according to the declining birth rate and ageing population, in 2020 some major cities began to relax their residency restrictions. However, these policies are aimed at university graduates and other preferred categories of the population. For ordinary urban workers, the minimum requirements to obtain urban hukou under the relaxed policies are still out of reach, such as paying into social security for a set number of years.

Population growth and geographical distribution

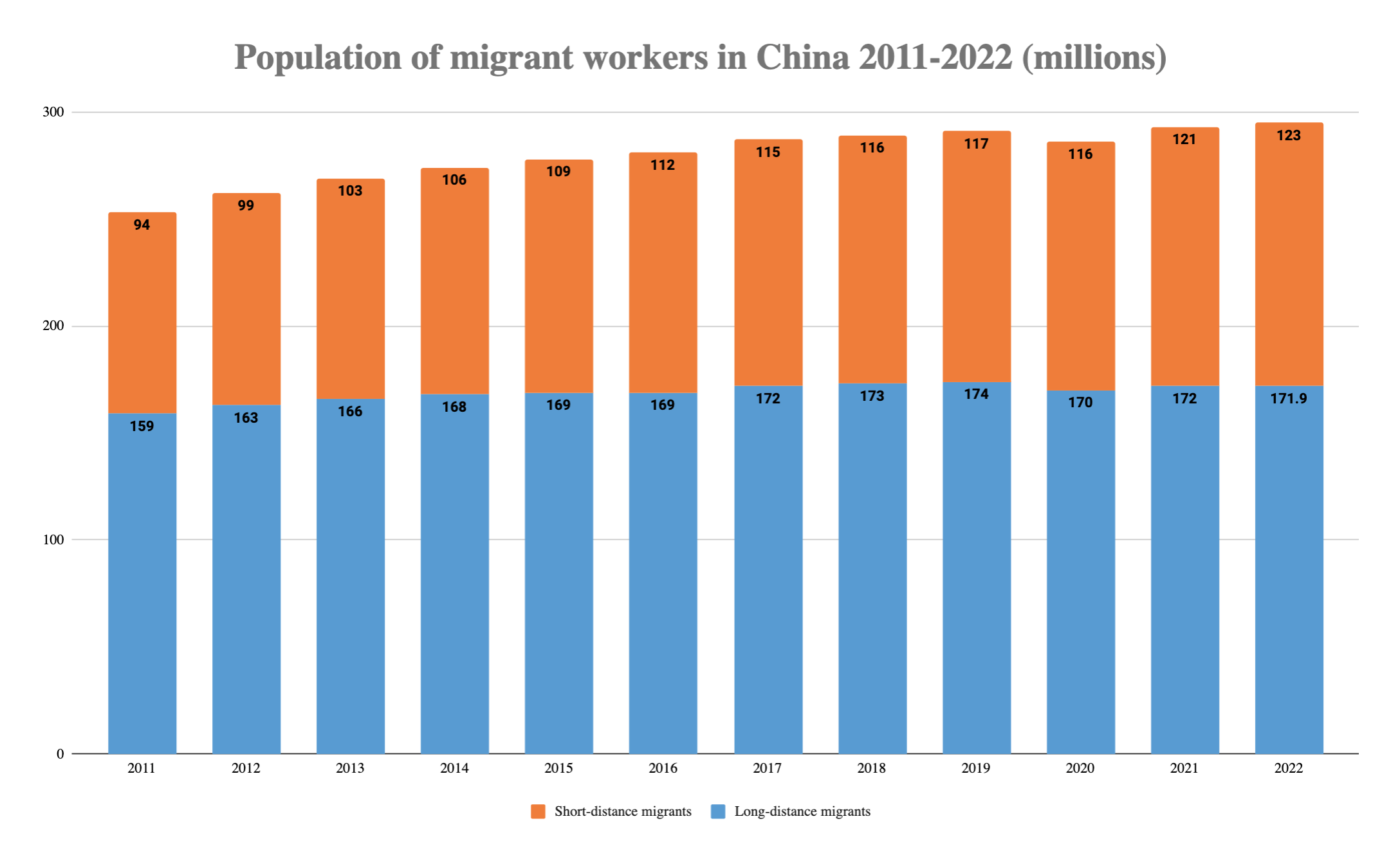

Rural migrant workers have been the most important engine for growth in China’s labour market for three decades and as of 2022 make up 33.7 percent of the total workforce of approximately 876 million. However, in 2022, the number of rural labourers working in China's urban areas increased by 3.1 million (1.1 percent) to 295.6 million, from 292.5 million in 2021, according to the annual survey conducted by the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS). Over the last ten years, the number of migrant workers has generally increased, although the growth rate slowed. Because of the effects of the global pandemic, 2020 was the first year the migrant worker population declined, dropping by 5.2 million. In 2021, the increase in the migrant worker population was larger than any since 2013.

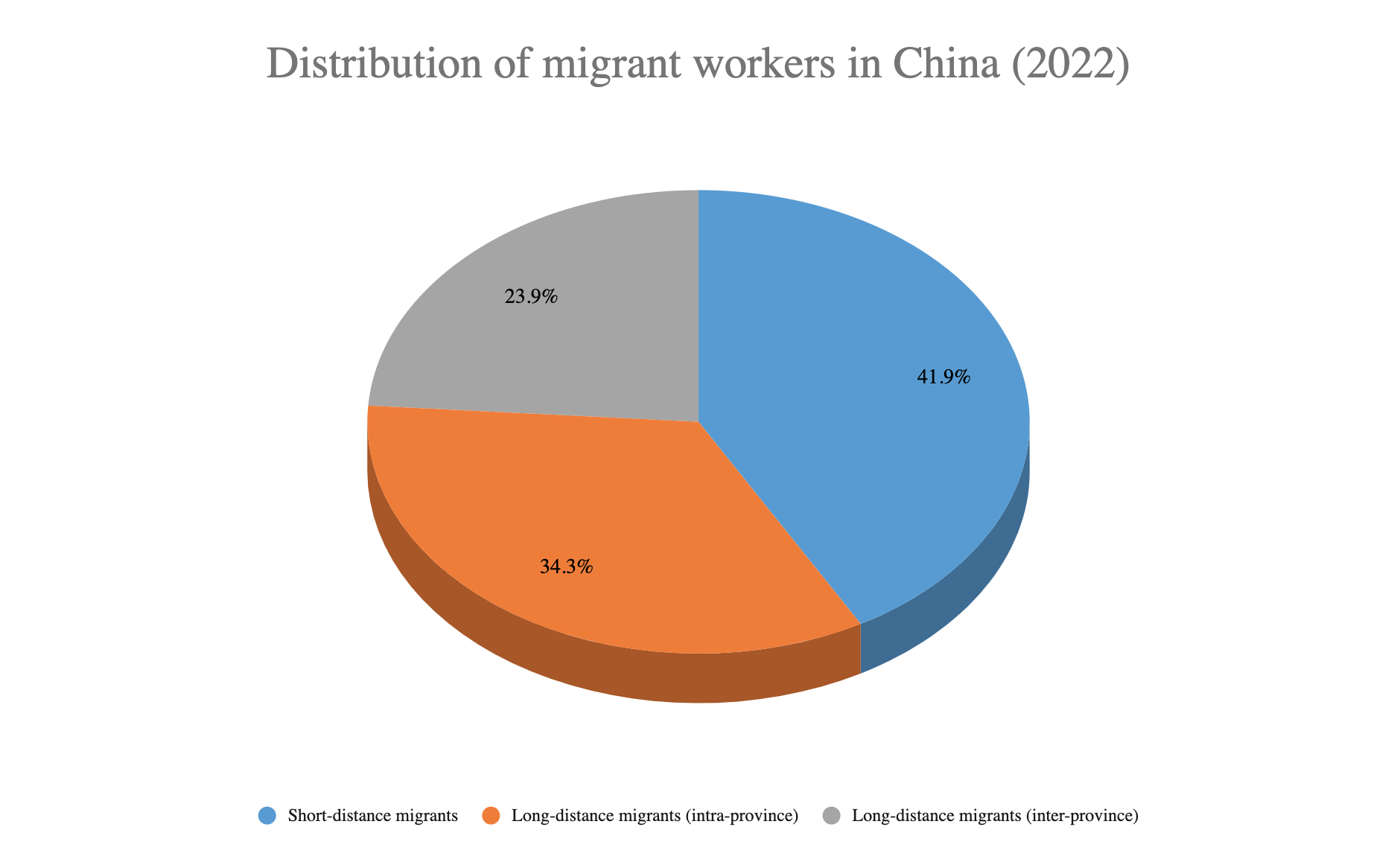

The NBS survey divides migrant workers into those working in a town or city close to their home area, usually within the same county (乡内), called short-distance migrant workers (本地), and those working in cities further afield (乡外), called long-distance migrant workers (外出). In 2022, there were about 172 million long-distance migrant workers, an increase of 180 thousand (0.1 percent) over the previous year. Among them, the population of inter-province migrant workers remained about the same compared to 2021 (decreasing only by 0.01 percent) whereas short-distance migrant workers increased by 2.93 million (2.1 percent). This is in line with a long-term trend toward a higher proportion of short-distance migrant workers (see chart below).

The number of short-distance migrant workers has increased at a much faster rate than long-distance migrant workers over the last decade; a 30 percent increase since 2011 compared with 8 percent for long-distance migrant workers. In the past, migrant workers often chose to move to China’s southeastern coastal manufacturing centres or larger inland cities where job opportunities and wages were better. But recently, small cities in both coastal and inland areas are more developed, allowing workers to be closer to home. For example, since 2022, factories in the traditional manufacturing centres of Shenzhen and Dongguan, in Guangdong province, have been relocating to other areas of Guangdong or to Guangxi province and recruiting local workers there.

Meanwhile, the conditions are deteriorating for migrant workers in the major cities such as Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou and Shenzhen. The number of long-distance migrant workers decreased by 690,000 (1 percent) in 2022. About 75 percent of all migrant workers are now employed in their own province. Only 23.9 percent travelled outside their own province for work, down from 24.4 percent in 2021. About 42 percent of migrant workers are employed in their home area, while the remaining 34 percent found work outside their home area but within their own province, usually provincial capitals or prefectural cities (see graph below).

The migration of labour in China is often seen as a simple, unidirectional movement from the less developed western and central regions to the manufacturing and urban centres of the east. Although this may have been broadly accurate more than ten years ago, just half of China’s migrant workers are currently employed in the more economically developed eastern provinces.

In 2022, the migrant worker population in the central provinces saw the largest increase, of 2 million (3.0 percent). The migrant worker population in the western provinces increased by 2.5 percent, and the migrant worker population in the eastern provinces remained basically stable. The migrant worker population in the northeastern provinces dropped by 5.7 percent.

Beginning in 2022, the National Bureau of Statistics no longer reports the number of migrant workers in each economic region. The last data available, from 2021, states that the number of migrants working in the traditional manufacturing hub of the Pearl River Delta fell from 2020, decreasing by 40,000 (0.1 percent), to stand at 42.2 million. This reflects that the region’s status as a traditional manufacturing sector is shrinking. The population of the Jiangsu, Shanghai, Zhejiang region increased by 1.6 million (3.1 percent) to 53.4 million, while the Beijing, Tianjin, Hebei urban region population increased by 490,000 (2.4 percent) to 21.3 million.

In late 2017 and early 2018, migrant workers in Beijing’s suburbs were evicted, which partly contributed to the migrant worker population in the Beijing, Tianjin, Hebei urban region decreasing by 1.2 percent in 2018. In 2019, the migrant worker population in the region rebounded slightly by 0.9 percent, but in 2020, it dropped by 6 percent due to the pandemic.

One consequence of the growth of employment for migrant workers in western and central China has been that provinces like Henan and Shaanxi have become major centres of worker activism and unrest, alongside traditional centres of activism like Guangdong (see CLB’s Strike Map for latest information on the distribution of strikes and protests in China).

Age, gender and education

The overall gender distribution of migrant workers in 2022 was 63.4 percent male and 36.6 percent female, compared with 64.1 percent male, 35.9 percent female in 2021. These numbers show a disparity with the gender distribution of the total population of workers, where women make up 43.5 percent.

However, it was slightly easier for women to find employment closer to home where family support is stronger. The proportion of women workers among short-distance migrants was 41.7 percent in 2022.

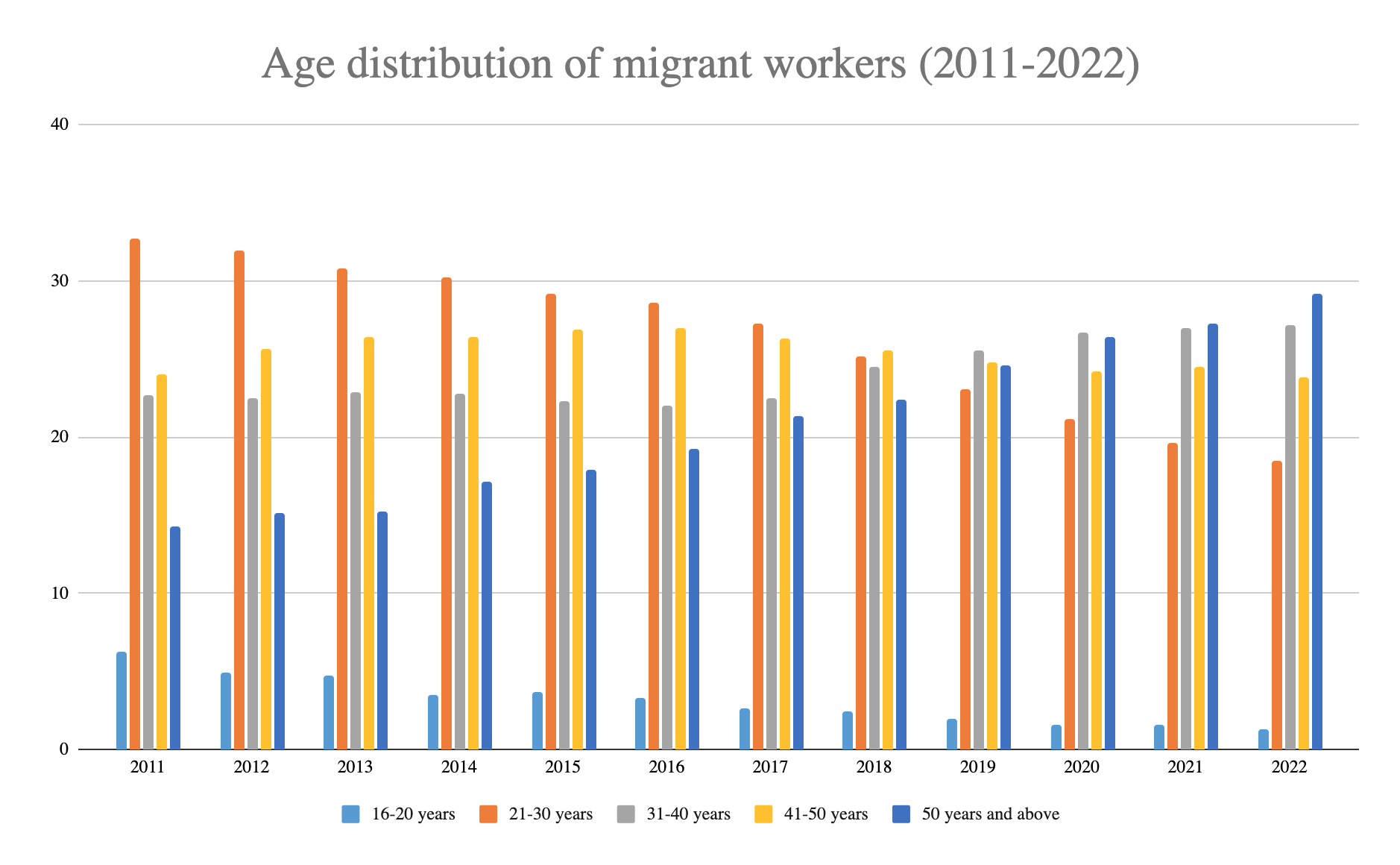

The average age of migrant workers in China has increased steadily over the last decade as fewer young people enter the workforce and older workers with no pension protection are forced to continue working. The average age in 2022 was 42.3 years compared to just 34 years in 2008. Almost 30 percent of all migrant workers are now over 50 years of age, and more than half (53 percent) are over 40, compared with 34 percent over 40 in 2010. The proportion of workers aged 16 to 30 meanwhile has fallen from 42 percent in 2010 to 19.8 percent in 2022 (see chart below).

The ageing trend is even more apparent among short-distance migrant workers where the average age is now 46.8 years, with a remarkable 41 percent over 50 years of age. For long-distance migrant workers, the average age is 37.4 years, with only 16.4 percent over 50 years, indicating that it is much easier for older migrant workers with families, as well as for women of all ages, to find employment closer to home. In many cases, however, short-distance migrants simply have to work well beyond retirement age because of a lack of sufficient pension protection.

The demographic patterns described above are also reflected in migrant worker education attainment levels, with long-distance migrant workers having higher levels of education than short-distance migrant workers. The proportion of long-distance migrants with some form of college education (18.7 percent) was twice as high as that of short-distance migrants (9.1 percent).

Employment patterns and wages

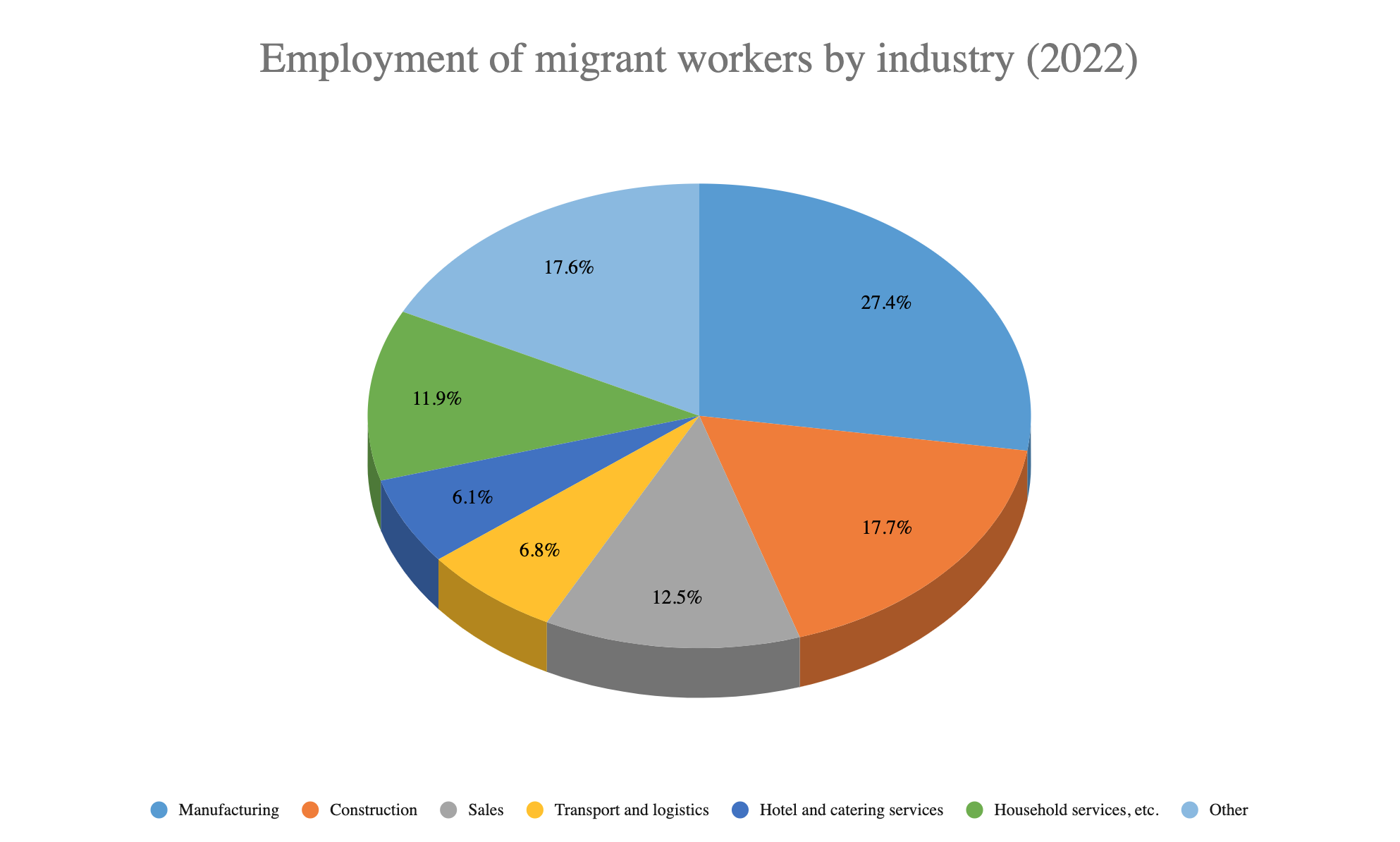

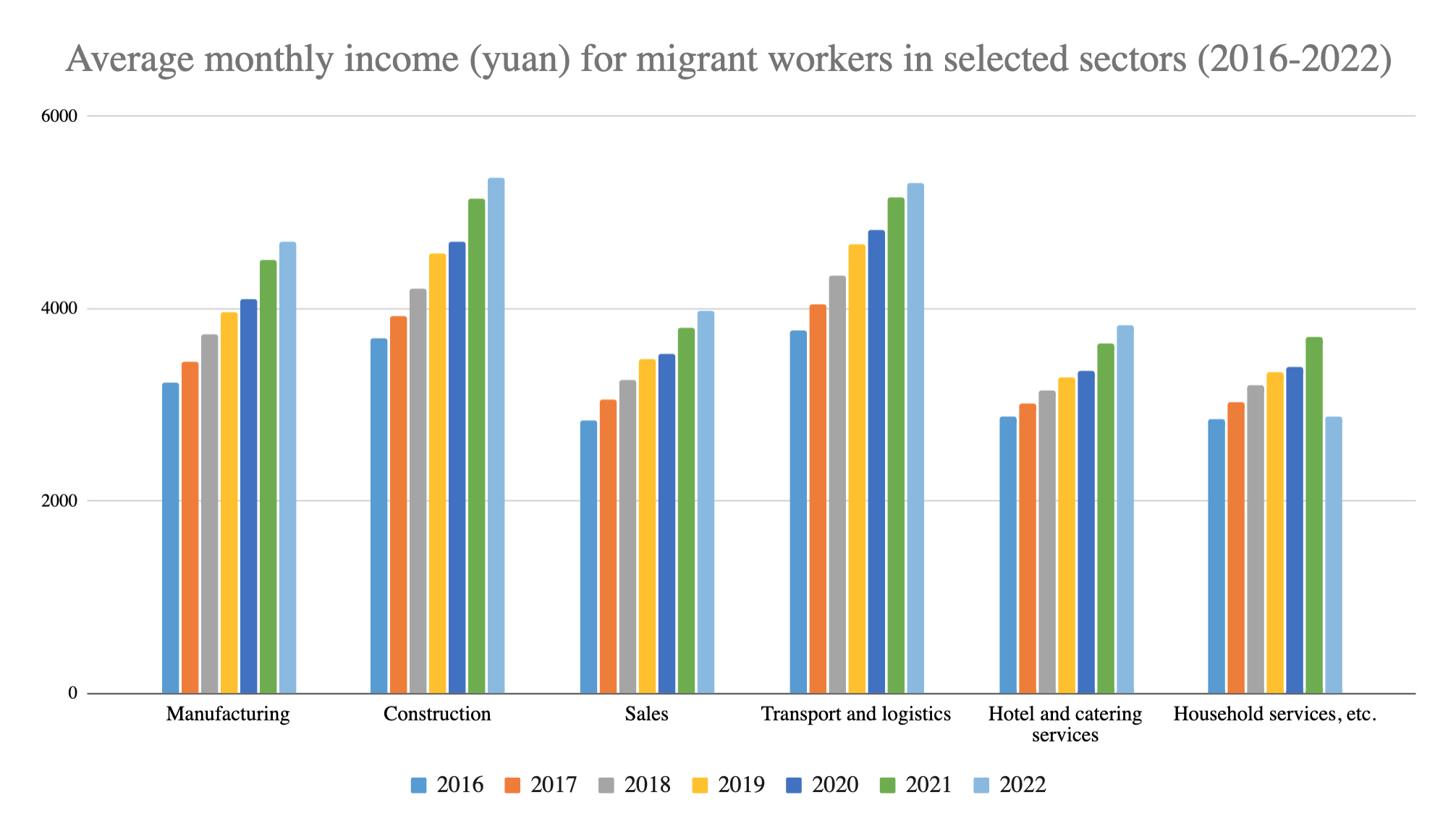

The vast majority of rural migrant workers are still employed in low-paid jobs in manufacturing, construction and an increasingly wide range of service industries (see chart below).

Services, including transport and logistics, now account for 51.7 percent of all migrant worker employment. The proportion of migrant workers employed in manufacturing has fallen dramatically from 36.7 percent in 2010 to 27.4 percent in 2022, reflecting both the decline in China’s manufacturing industry and greater opportunities for migrant workers in other sectors. The proportion of migrant workers in the construction industry reached 22.3 percent in 2014, at the height of the infrastructure, residential and commercial property building boom, but has declined steadily since, dropping to 17.7 percent (over 52 million workers) in 2022.

Wage levels for migrant workers have grown steadily, albeit increasingly slowly, over the last decade, with the average monthly wage in 2022 standing at 4,615 yuan, up 4.1 percent from the previous year. The headline inflation rate in China in 2022 was 2.0 percent, showing an increase in wage levels.

The highest-paid sectors for migrant workers in 2022 were construction (5,358 yuan per month average wage) and transport and logistics (5,301 yuan per month average wage), while those employed in hotel and catering services, and household services, repairs, etc., were the lowest paid, earning just over 3,820 yuan per month (see table below).

The substantial gap in earnings between short and long-distance migrant workers remained stable in 2022 with the average wage of long-distance migrants increasing to 5,240 yuan per month, and the average wage of short distance migrants increasing to 4,026 yuan, leaving an overall average income gap of 1,214 yuan per month. Wages in the eastern provinces increased by 4.5 percent, with migrant wages reaching 5,001 yuan per month. Wages in the central and western provinces increased by 4.3 and 3.9 percent, respectively, reaching 4,386 yuan and 4,238 yuan. Wages in the northeastern provinces saw the smallest increase at 0.9 percent, to 3,848 yuan per month.

Working conditions and benefits

In addition to low pay, migrant workers often work long hours, have little job security and few welfare benefits. The NBS survey no longer includes data on working hours, wage arrears, employment contract signing rates, social insurance coverage, etc. However, anecdotal evidence from other sources suggests there has been little improvement in working conditions. Indeed, CLB’s Strike Map regularly records collective protests by low-paid workers in construction, transport and logistics, and a wide-range of service industries over wage arrears, social insurance, and precarious employment.

The last mention of employment contract signing rates in the NBS survey was in 2016 when 35.1 percent of migrant workers had a contract, significantly down from a high of 42.8 percent in 2009. At that time, one year after the implementation of the Labour Contract Law, there was a concerted push to ensure contracts were signed, but that initiative soon faded and precarious work gradually became the norm, not only in the construction industry where the problem is endemic but in manufacturing, where workers are hired through agencies and on short-term contracts, and in many of the new service industries that are absorbing much of the migrant workforce.

Despite some improvements in social insurance coverage, the proportion of migrant workers with a pension or any form of social insurance is still at a very low level. The Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security reported that in 2017 only about 22 percent of migrant workers had a basic pension or medical insurance, 27 percent had work-related injury insurance, and just 17 percent had unemployment insurance, an increase over the five years since 2012 of 36.5 percent, 24.6 percent, 9.3 percent and 81 percent, respectively. It was estimated that around 40 million construction workers (74 percent) had work-related injury insurance, but this was largely because employer contributions are comparatively low, and — given the high rate of accidents on construction sites — it benefits the employer to pay for work-related injury insurance. For more details, see the section on the social security system in China.

The 2022 NBS survey did, however, discuss the issue of migrant workers joining trade unions. In all, 16.1 percent of migrant workers living in cities had joined union organizations, an increase of 1.6 percentage points from the previous year. Among the migrant workers who had joined the union, 82 percent participated in union activities, 2.5 percent less than the previous year. While the proportion of migrant workers joining the trade union is slowly increasing, it should be noted that migrant workers rarely go to the union for help in resolving labour disputes. According to data from 2017, only 2.8 percent of migrant workers living in cities approached the union for help in resolving disputes.

Living conditions

The 2022 NBS survey claims that migrant workers with a long-term presence in urban areas have on average 22.6 square metres of living space per person, an increase of 0.9 square metres over the previous year. In cities with a population of more than five million (a medium-sized city in China), however, the average living space falls to just 17.6 square metres per person.

Many migrant workers now rent accommodation rather than live in worker dormitories, with a smaller proportion owning their own home. In the vast majority of cases, migrant workers and their families are excluded from public housing. In larger cities, many migrant workers can only afford to rent small apartments in poorly-constructed or dilapidated buildings in remote parts of the city, and even these dwellings can take up a sizeable proportion of their monthly salary. In Shanghai’s Baoshan district in 2018, for example, migrant workers could rent a tiny room with a shared kitchen and bathroom for between 500 yuan and 1,000 yuan per month, depending on the length of the rental period. The cost of an apartment with a private kitchen and bathroom was a few thousand yuan a month. A survey of migrant residents in this area found that most were employed in nearby auto components plants or worked as supermarket clerks, restaurant staff, cleaners, and day labourers. The highest salary was 5,000 yuan per month and the lowest was 2,600 yuan per month.

For children growing up in this kind of environment, the risks can be deadly as was tragically illustrated by a fire in an over-crowded apartment complex in the southern outskirts of Beijing that killed 19 people, including several children, on 18 November 2017. Many migrant parents choose to leave their children in their hometown while they work in the cities but here the risks and dangers are just as apparent.

The pandemic had a huge impact on migrant workers based outside their home province. They faced the high costs of travelling to and from their hometowns and quarantine, and also lost their livelihoods and went without sufficient food under lockdowns. CLB followed calls for help from Shanghai workers throughout the pandemic. On 13 April, 2022, 200 workers assigned to the fourth phase of Haifu City Garden in Pudong New Area found themselves trapped by lockdown, and had no supplies delivered to them. They cooked noodles and cabbage in kettles. On 19 April, 2022, workers at a construction site in Sunqiao Town, Zhangjiang Road, Pudong New Area, were also exposed to the virus, but the local government took no isolation and relief measures. Parcel and food delivery workers slept under bridges and on the streets. Many truck drivers across the country had to eat, drink, and sleep in their trucks.

The children of migrant workers

In November 2009, China Labour Bulletin published Paying the Price for Economic Development: The children of migrant workers in China. This in-depth report outlined problems faced both by children left behind in the countryside and those travelling with their parents to the city, and examined central and local government policies put in place to deal with these issues. More than a decade later, many of the problems outlined in the report, such as institutionalised discrimination, limited access to education, healthcare and social welfare, remain unresolved.

Definition and population change

The children of migrant workers are broadly defined as those under 18 years of age who are affected by their parents’ migration for work; they include both children who travel with their parents to a town or city and those that remain in their hometown while one or both parents migrate.

The most recent official data available is jointly released in 2023 from the National Bureau of Statistics, the United Nations Children’s Fund, and the United Nations Population Fund in their “China’s Child Population Status in 2020: Facts and Figures” report. This report estimates the total number of children of migrant workers has reached 138 million or about 46.4 percent of the total number of children in China. Out of this total, there were an estimated 71 million children who migrated with their parents, and 67 million children who remained in their hometown, in both rural and urban areas.

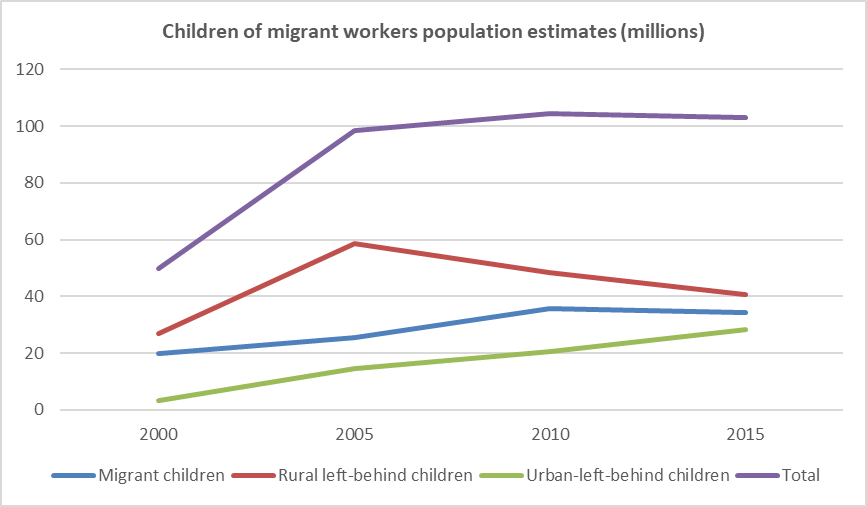

The total population of migrant workers’ children has remained constant at around 100 million since 2005 but there has been a noticeable change in the composition of that population due to rapid urbanization and absorption of rural areas (see graphic below).

Sources: National Bureau of Statistics; 2000 and 2010 population census, 2005 and 2015 1% National Population Sample Survey.

The relative decline in the number of rural left-behind children is sometimes seen as evidence that the situation for the children of migrant workers is improving. However, many formerly rural children live in newly created small- and medium-sized cities with limited social services and few decent job opportunities. Their parents often have to find work in larger cities and their children still struggle to find decent schools and medical care.

Family support

A healthy and positive family environment is crucial to a child’s development. The greater the support from their parents and wider family, the greater the child’s ability to develop physically, mentally and socially. The vast majority of migrant workers, however, simply do not have the time, ability or resources to provide their children with the support they need. They are either physically separated for long periods of time, work long and anti-social hours, or lack the education needed to help their children with their school work. Most migrant workers spend far less time reading to their children and helping with their homework than their middle-class urban counterparts, and cannot afford to pay for the books and extra-curricular activities urban children take for granted.

A survey of 1,518 migrant workers in 2013 revealed that they spent on average 11 hours at work each day. About half (52 percent) regarded themselves as “unqualified parents,” without sufficient time or ability to accompany, communicate with and assist their children with their homework. Despite improving education levels in the migrant worker population, even in 2020, 55.4 percent of migrant workers had a middle school education, and 14.7 percent only had a primary school education.

Many migrant workers take a simplistic approach to their children’s education, focusing more on grades than the actual process of learning and growing that helps a child’s development. Typically, parents will punish their children for low grades and reward them with cash when they succeed. Migrant workers, like all parents, tend to have high expectations for their children but their parenting style can leave their children at a disadvantage.

Children living in rural areas with a single parent, grandparents or in the care of other relatives or friends face similar problems; a lack of direct parental contact and caregivers unable to provide the support they need. The non-profit organisation, "On the way to School (上学路上),” found that more than 40 percent of school children left behind in the countryside saw their parents more than nine times a year, while 12 to 13 percent of children didn’t see their parents at all. Around 25 percent of respondents received a call every three months, and four percent received one call a year. Another survey in 2017 found depressingly similar results. Eleven percent of the children surveyed claimed that their parents were dead, a way of expressing their anger at absent parents, when the actual number was estimated to be less than one percent.

Children who grow up in impoverished and remote rural areas with their grandparents as the primary caregivers are likely to be disadvantaged in terms of their psychological and educational development. Studies have shown that many elderly grandparents are poorly educated; most have only completed primary school and speak local dialect rather than Mandarin which is the language of instruction in nearly all Chinese schools. Grandparents often cannot assist their grandchildren with schoolwork, focus only on their physical needs, and overlook their developmental and emotional needs. Left-behind children often report a sense of emotional detachment from their grandparents. As one secondary school student said: “I help [my grandparents] cook and we watch television together but we don’t really talk.”

Education

The Compulsory Education Law states that all children should receive nine years of schooling. The law stipulates that “the state, community, schools and families shall… safeguard the right of compulsory education of school-age children and adolescents.” The reality, however, is that the state has not ensured unrestricted access to public education for all migrant children.

According to the 2022 Statistical Bulletin for National Education Development, children who had moved to cities accounted for 13.6 million of the students in compulsory education. Of these, 9.7 million had enrolled in primary schools and 3.9 million in middle schools. The NBS Migrant Workers Report for 2022 stated that 88.3 percent of children at primary school age were enrolled in public schools, and 87.8 percent of children of middle school age were enrolled in public schools. These data sets indicate that 1.13 million primary school age migrant children and about 481,000 middle school age migrant children did not attend public schools.

The last public data on access to education is from the 2020 NBS survey on migrant workers, which showed that only 81.5 percent of migrant children in the compulsory school-age-range had access to public schools in the city, a decline of 1.9 percent compared with the previous year. Nearly half (47.5 percent) of the migrant workers surveyed said they had experienced problems related to their children’s schooling; the main issues being, finding a school, paying fees, and leaving children unattended. The attendance rate in kindergarten for migrant worker children was 86.1 percent, but the vast majority of kindergartens are private, fee-paying institutions that provide limited services.

To secure a place for their child at a public school, parents routinely have to negotiate a maze of obstacles erected by local education departments, especially in big cities that jealously guard their education resources. In Guangzhou for example, migrant parents have to produce temporary residence permits, work permits, proof of residence, certificates from their place of origin, and household registration booklets to apply for a school place for their children. Those who secure a place in public schools often face prejudice and discrimination, excluded from extracurricular activities and treated as outsiders. According to one survey in 2012, 86.3 percent of migrant children had not made any friends among local children, while 7.1 percent did not have any friends at all.

Private schools often provide a more familiar environment and some schools are relatively affordable but they are often unregulated, over-crowded and have poor facilities. A report on 300 migrant schools in Beijing for example, showed that only 63 were licensed. Teachers’ wages were low and the workload was intense. Many teachers only accepted jobs in migrant schools as a stepping stone to a better position at public schools and, as a result, teacher turnover was very high.

Moreover, migrant schools in major cities like Beijing run the constant risk of being closed down by the authorities on any pretext. The local authorities in Beijing have launched numerous campaigns over the last decade or more to crack down on unlicensed migrant schools claiming they were unsafe. In reality, many demolished schools had passed several government checks and, in most cases, the real reason for school demolition was to make way for new commercial and housing developments. Beijing launched yet another crackdown on migrant schools in 2017 during which one of the largest migrant schools in the city with about 2,000 students, the Beijing Huangzhuang School in Shijingshan district, was ordered to relocate even further outside the city by January 2018. Demolition work began in October 2017, just prior to the 19th Party Congress.

After a migrant school is closed down, parents face a difficult choice: either send their children to a migrant school in an even remoter part of the city, try to find a place in a public school, or send their children back “home” to study there. In all cases, however, students are forced to adapt quickly to a new and unfamiliar environment, putting even more pressure on their studies.

The final educational hurdle for migrant children has long been the national university entrance examination. Even if they have spent nine years in an urban school, students nearly always have to take the exam in their “home town.” Each region sets its own curriculum, so migrant students are at a distinct disadvantage. Moreover, many migrant students who return home to study high-school have trouble adapting to this new environment and simply drop out. A survey of 137 schools in five cities and counties in Hebei and Sichuan found that 65.5 percent of returnees had both parents absent, compared to 45 of non-returnees. Adjustment is often difficult with 64.3 percent of returnees at high risk of developing depression, and 22 percent of returnees having to repeat a grade.

There have been attempts to open up university entrance exams to migrant students and some students can now sit for the entrance exams in the city they reside in. However, the threshold for eligibility is very high, making such concessions effectively worthless. Many areas have requirements regarding length of parents’ employment, duration of residency, payment into the social security system, etc., and place priority on the continuity of students’ academic status in the local area. In 2013, more than 20 provinces indicated that they would relax exam restrictions to some degree but only a few thousand migrant students actually benefited. Any further relaxation of the system will likely meet strong resistance from local students and their parents in major cities who are concerned that competition for university places will intensify if more migrant students become eligible.

In 2020, 256,000 migrant children took the university entrance exam in their place of residence, a huge increase from 4,400 in 2013. However, they accounted for 2.39 percent of the total number of students taking the exam. In 2019, only 373 migrant children took the university entrance exam in Beijing, out of a total number of 59,000. In addition, children of migrant workers are only eligible to take the “Higher Vocational Admissions Examination” in Beijing, which qualifies them for vocational schooling rather than undergraduate universities.

While migrant children face numerous challenges in larger cities, the situation in rural areas and most smaller cities is even worse. Rural schools are underfunded, under-resourced and find it difficult to hire and retain qualified teaching staff. Many rural teachers are so-called community teachers (民办教师) who earn about one third of the salary of their urban counterparts and are routinely denied the pensions and other benefits they are legally entitled to.

In the 2000s, China launched a national policy to close and consolidate rural schools (撤点并校) under which about 300,000 village primary and middle schools were closed down between 2001 and 2009. Students were forced to either go to boarding schools or endure long, arduous journeys every day to attend school in the nearest town. Class sizes in the new centralized urban schools ballooned with the average number of students in some cases exceeding well over a hundred, placing massive strains on the teaching staff. The rural school closure and consolidation policy was officially discontinued in 2012 but small rural schools have not reopened and local governments continue to close down schools unilaterally in a bid to save money. In 2015 alone, more than 10,000 primary schools closed their doors, mostly in rural areas.

The 2014 Rural Education Action Program (REAP) research group survey estimated that only 37 percent of rural students were able to enter high school after graduating middle school, compared with a 90 percent rate for students in major cities. For children in poor rural families, just about the only higher education option is a lower-level high school or vocational school that cannot guarantee better career opportunities or even basic skills training. Tuition fees, even in low-level high schools and colleges, are expensive and many students take out a loan to pay for school fees and expenses.

Millions of poor rural students enter the workforce every year directly after leaving middle school, some even before graduating. The dropout rate for rural students in 2013 was about 24 percent, compared to the average rate of just 2.6 percent, according to the REAP research group survey. CLB’s 2008 research report on child labour showed that middle school dropouts are a major source of under-age work in China. While poverty reduction programs have improved the situation somewhat, cases of child labour are still reported from time to time. In August 2017, 18 “orphans,” between the ages of 11 and 14, from the impoverished Daliangshan district of Sichuan dropped out of school to work in a fight club in the provincial capital Chengdu. After media coverage, the Daliangshan local government forced them back to school but the children were reluctant to go. One child said in an interview, “I do not want to go back to my poor hometown, it is nothing but poverty, I would just become a drug addict or a thief, like everyone else.”

On 25 February 2021, China’s paramount leader Xi Jinping announced “complete victory” in the war against extreme poverty. Under Xi’s administration, Xinhua claimed, 99 million poor rural residents have been lifted out of poverty, and 832 impoverished counties and 128,000 poor villages removed from the poverty list. While Xi's poverty alleviation campaign improved infrastructure links for remote areas, there is less tangible evidence that education and healthcare services have also improved.

Healthcare

For low-income migrant families, seeing a doctor in China’s commercialized healthcare system can be prohibitively expensive. The Statistical Bulletin for National Health and Family Planning Development reported in 2021 that the national average fee for outpatient services in general hospitals was 329.2 yuan per visit and the average fee for in-patient services was 11,002.9 yuan or 1,191.7 yuan per day. The average monthly income for migrant workers in 2021 by comparison was just 4,432 yuan. This means that many migrant workers will only visit a doctor in dire emergencies.

Community and village clinics are relatively cheaper, with outpatient costs at 164.3 yuan per visit and inpatient costs at 3,649.9 yuan on average for community clinics, and 87.5 yuan and 2,166.5 yuan for village clinics. However, community and village clinics are poorly equipped and lack qualified nurses and doctors, and can only provide basic care.

The central government has introduced several different insurance schemes over the last two decades designed to make healthcare services more affordable to migrant workers and rural residents. However, the children of migrant workers, especially pre-school children, often fall outside the remit of such schemes.

There are three main types of medical insurance in China but none of them effectively cover migrant children before they start school.

- The basic medical insurance scheme for urban employees should cover all urban workers, including migrant workers, but very few migrant workers are covered in reality. As noted above, only about 22 percent of rural migrant workers had employee medical insurance in 2017. Those who do have insurance have to present a certificate of study for their children to qualify for benefits, which effectively excludes pre-school migrant children and those in unregistered private schools from the scheme.

- The urban resident basic medical insurance scheme covers unemployed urban citizens, including students and retirees, but not migrant workers.

- The new rural cooperative medical care scheme is often the only option for poor migrant families with preschool children. However, this scheme is designed to cover only rural residents and as such it requires individuals to purchase insurance and claim compensation in their hometown, which makes it impractical for migrant workers.

Some regional governments have set up insurance schemes for minors regardless of their hukou. Migrant children in Shenzhen and Hangzhou, for example, can get the same level of insurance as local children but this is far from a nationwide practice.

In nearly all insurance schemes in China, patients have to pay for treatment first and receive reimbursement later. Migrant workers face the additional burden of having to travel back to their hometown to claim reimbursement. In March 2021, Premier Li Keqiang announced a new initiative in which the government would, within two years, make sure that every county in China had a fully operational centre to immediately process medical insurance claims for migrant workers and their families.

However, in most cases, insurance companies will only reimburse a fraction of the cost of medical treatment. In 2014, it was estimated that the parents of children with serious illnesses could only recoup 20 percent to 45 percent of the cost of treatment, and even less if the cost was in excess of 200,000 yuan.

Several regional governments have implemented vaccination schemes that include both local and migrant children. However, the take up rate of migrant children is usually lower because their parents are often unaware of such schemes. The high mobility of some migrant children also makes it more difficult for the officials to determine their health history and as such some regional governments have pioneered a registration system for migrant children aged under 16 aimed at enhancing communication between children’s home town and their city of residence, sharing data on social security, healthcare and education.

In rural areas, the new rural cooperative medical care scheme covers most families. However, the lack of decent medical facilities in rural areas means that children with serious or rare medical conditions have to go to specialist hospitals in larger cities. Many rural families run up massive debts trying to treat children with serious illnesses, others simply give up. The National Health Commission estimates that parents abandon around 100,000 children every year in China, many because of illness or disabilities.

Community and social support

Apart from basic institutional support structures like schools and hospitals, children also need support from the wider community to ensure healthy growth and development. In this regard too, the children of migrant workers are seriously disadvantaged. Middle-class children living in big cities usually have access to a wide range of educational and recreational facilities; libraries, museums, sports grounds, youth clubs, private tutors, as well as childcare facilities and domestic helpers who provide support for children when their parents are at work. Cities also have a range of emergency support facilities such as hotlines and community outreach programs that provide a safer, more nurturing environment for children.

Migrant children do, in theory, have access to these facilities but uptake is low. Most migrant children live in remote areas of the city with poor transport links and limited facilities. The big museums and libraries tend to be downtown and can seem a world away for migrant children who often feel intimidated and unwelcome in these places. Even if they want to go, it is unlikely that their parents can afford the time or money to take them. Beijing civil society organization Facilitators noted that migrant children often do not identify with urban children because of discrimination they and their parents endure. As such, they are reluctant to engage in public activities or use public services urban children take for granted.

In rural areas, almost all left-behind children lack access to decent public resources and community support. A survey of 4,533 left-behind children in 2014 found that about 17 percent considered themselves to be their main source of social support, and 23 percent said they had no one to turn to when in need of help. Without enough parental and community support and a safe educational environment, many left-behind children fall victim to bullying, physical and sexual assault. A 2019 White Paper on the Mental Status of Left-behind Children examined four categories of violence against children: physical, mental, and sexual abuse, and neglect. In the survey areas of Jiangxi, Anhui and Yunnan, 65.1 percent suffered physical abuse, 91.3 percent mental abuse, 30.6 percent sexual abuse, and 40.6 percent suffered from neglect. Nearly 14 percent of children said they had experienced all four categories of abuse. School bullying and psychological violence in the family were frequent, the report added.

Migrant workers’ children are also much more likely to be the victim of accidents because of the lack of parental supervision. A nationwide survey in 2014 showed that close to half of all left-behind children (49.2 percent) had sustained injuries during their normal day-to-day life, 7.9 percent higher than that of children with their parents. Injuries included animal bites, burns, electrocution, falls and poisonings.

One of the most talked about problems with the children of migrant workers has been their well-documented delinquent behaviour and criminal activity. For example, a 2016 survey of male prisoners found that 17 percent were formerly left-behind children. However, as noted above, left-behind children are all too often the victims of crime as well, just as children in disadvantaged communities across the world are.

The hukou system does create some very peculiar difficulties for the children of migrant workers in China, such as the college entrance exam discussed above. However, the fundamental issues are the same as in many other developing countries, where the grossly unbalanced distribution of wealth and economic resources between urban and rural areas has created a vast class of low-paid and socially disadvantaged workers with very limited opportunities for upward mobility.

Urbanization, hukou reform and social justice

At the end of 2022, China’s urban population exceeded 65 percent of the total population. However, only three quarters of the urban population actually have an urban hukou. The most recent data from 2021 show that 46.7 percent of the total population had an urban hukou, but 200 million migrants did not have an urban hukou.

In 2022, Tsinghua University’s China New Urbanization Research Institute Executive Vice President, Yin Zhi, stated that for the approximately 200 million migrants entering urban areas, they lack access to urban services and are in a “low-level urbanization state.” About 133 million migrant workers live in cities as of the end of 2022, about 44.8 percent of the total migrant population. The People’s Daily reported that the number of migrant workers and their accompanying families in cities has been gradually decreasing since 2018 and especially because of the effects of the pandemic. In 2020, there was a year-on-year decrease of 6.83 million. In 2021, the year-on-year change was a slight increase, but compared with 2019 was a decrease of 6.14 million. Migrant workers were typically the main force in the urbanization growth in China, but as this group decreases, urbanization rate of the permanent population will slow in the future.

The gap between urbanization and urban hukou rates has narrowed gradually but China’s new urban residents are not necessarily better off than when they were rural residents. Many newly urbanized families were only granted a hukou after their rural land was forcibly acquired by local governments in league with major property developers. In return for giving up their rural land rights, new urban residents are usually granted a place in a small or medium-sized city with limited social services in the same province as their previous rural residence. The only cities and regions really willing to relax hukou restrictions have been rapidly-growing county and prefectural cities that need new residents and do not have a substantial and entrenched urban population that sees rural migrants as a threat to their resources. In May 2018, for example, Hainan announced a plan to lure one million new residents by 2025, ostensibly high-skilled workers who can help develop and capitalize on the province’s new free trade zone status. More cynical observers see the scheme as a way to shore up Hainan’s rapidly cooling property market.

The southern metropolis of Guangzhou grants around 100,000 urban hukous each year but again nearly all the beneficiaries come from the surrounding province of Guangdong. Migrants from nearby provinces like Hunan and Sichuan still struggle to get a Guangzhou hukou. The situation is even worse in major cities such as Beijing and Shanghai that have both announced population caps of 23 million and 25 million people respectively. Beijing has already taken draconian measures to remove its so-called “low-end population” (低端人口) and Shanghai might have to resort similarly coercive tactics if it is to achieve that target.

The central government’s Key Tasks for New Urbanization and Urban-Rural Integration Development in 2021 relaxes restrictions on urban settlement, but primarily for smaller cities and towns, and central and western regions. According to a draft of the government’s 14th Five Year Plan, the household registration system will be abolished entirely in cities with a population of up to three million and relaxed in cities of between three and five million, although exceptions may apply. Larger cities will continue employ a points system that allows them exclude low-income and transient workers from the municipal welfare system

The majority of people in China probably agree that the household registration system is archaic and unfair and that rural hukou holders working in the cities should be given greater access to schooling, social and medical welfare benefits.

A Caixin editorial back in March 2012 described the system as “morally indefensible in today’s China,” adding that:

Reform for the hukou system would represent a timely investment in human capital that's conducive to economic growth. There is broad consensus that China should move forward with more hukou adjustments. The country has spent years preparing for change, and has now taken first steps. It's time for more.

Nearly a decade later, however, the hukou system remains stubbornly in place in major cities. The needs of individual cities for land, labour and other economic resources will determine the extent and pace of any future hukou reform, rather than desire for social justice.

That said, one crucial obstacle to hukou reform at a national level, namely the staunch opposition of China’s police force, might be on the wane now that technological advances such as facial recognition software and social credit scores have given the police additional and potentially much more effective means of social control.

At some point in the future, the central government in Beijing may have the political will to push through hukou reform. Until then, a far more pressing need is for a genuine commitment to enhancing social justice, reducing the gap between rich and poor, and increasing social mobility. China Labour Bulletin recommends that the government adopt the following measures:

- Ensure that all children living in the same city have equal access to public health and education services, and the same opportunities for social advancement and social participation, regardless of their hukou status.

- Invest in affordable and accessible housing so that rural migrant workers and their families are not forced to live in over-crowded, poorly constructed and often hazardous apartment buildings in remote shanty towns.

- Central and provincial governments should provide subsidies to small and medium-sized cities to build hospitals and other essential public services for the local population and surrounding rural areas, thereby reducing the need for rural residents to travel to major cities for medical treatment.

- Subsidies should also be available for developing rural education. Local governments should build new schools and attract better qualified teachers with higher salaries and benefits.

- All sectors of society, government, schools, media and civil society organizations should focus on accelerating urban integration and resisting attempts to label migrant workers as the “low-end population.”

A version of this article was first published in 2010. It was last revised and updated in September 2023.

Some of the original links to Chinese-language sources are no longer available and have been deleted from the text.