In this series, CLB investigates cases of platform workers to raise the specific challenges and potential solutions for how China’s official trade union could represent them, both individually and as a sector. Read more here.

- In the midst of an expansion drive, China’s official union has said it wants to be the first stop for workers in difficulty, so that “when they have a problem, the first thing they think of is the union.” But for workers in the decentralised platform economy, the question is often far more basic: which union can and will take responsibility to help them? The answer is often, none.

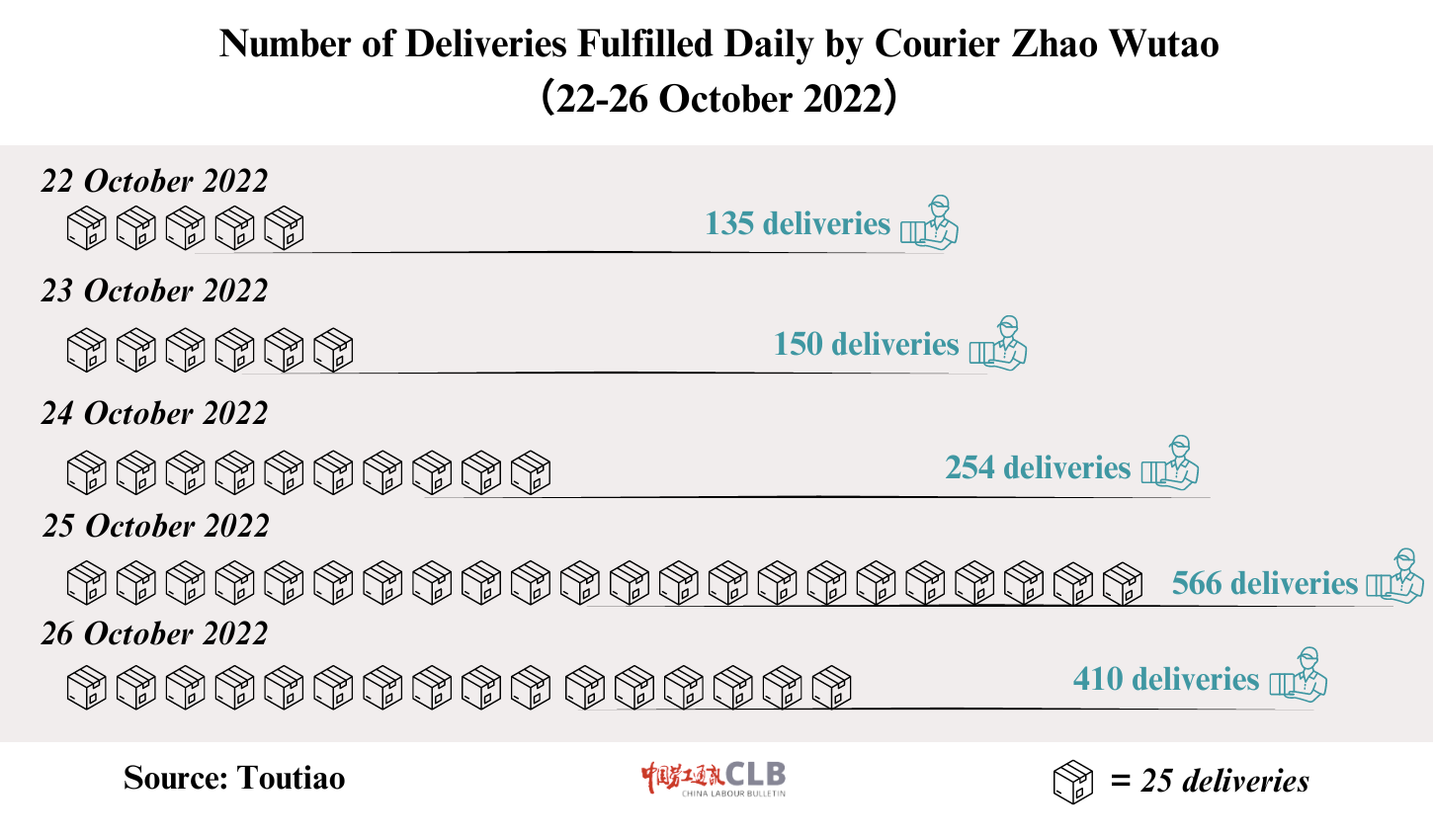

- Zhao Wutao died from overwork in the lead-up to China’s annual November shopping holiday, delivering 566 packages in a single day. But the process of establishing this as a work-related accident for his family to receive compensation is an uphill battle, and none of the unions CLB reached out to were willing to help.

As China’s leadership pushed for reform of the official union in the mid-2010s, workers in the platform economy and other non-standard forms of employment have since become a priority for the All-China Federation of Trade Unions (ACFTU). One focus has been the unionisation of transport and service workers from the so-called “eight major groups,” and this process has resulted in hundreds of enterprise unions inside platform service companies, the establishment of regional unions for these workers, and an upsurge in hiring for union roles.

The basic idea behind this unionisation drive is that the rights and interests of platform workers can be better served through the existing ACFTU structure. It has become routine to hear union officials say in official news coverage in recent years that platform workers should better understand the role of the ACFTU, so that “when they have a problem, the first thing they think of is the union.”

Photograph: canghai76 / Shutterstock.com

Even as unionisation progresses, however, the process has not kept pace with the labour relations changes brought on by the rise of the platform economy. Workers who require urgent assistance might benefit from the intervention of the union in defending their rights before employers, or in seeking justice through the courts. But what they often find is that their cases are caught up in an endless cycle of denials over which union has “jurisdiction" (属地主义), so the typical result is that no union is willing to take on the case.

In other words, there are numerous unions at various levels that could step in to help any given worker, but they each disclaim responsibility by pointing to a union in another jurisdiction as the one with the real authority to act.

The growing problem of union jurisdiction in the fragmented platform economy came to the fore in November 2022, as a package courier originally from Henan province died suddenly in Beijing due to overwork in the run-up to China’s annual November online shopping season.

The courier, Zhao Wutao (赵武涛), had been engaged for years by a local express delivery hub for Yunda Express in Beijing’s Fengtai District, working outside of a formal employment contract. Without that contract, the local hub refused to offer his family work-related accident compensation. The platform company, Yunda Express, is headquartered in Shanghai, and establishing a labour relationship with it would be even more daunting.

Cases like Zhao’s offer a glimpse into the jurisdictional loopholes that stand in the way of the rights of platform workers and enable delivery service providers and major platform companies to avoid legal responsibility for rights violations, even as the process of unionisation continues. Unions should step up in individual cases like Zhao’s, and also work to solve the systemic problems that affect all platform workers in China every day.

The fragmented case of the overworked courier Zhao Wutao

On 3 November 2022, Zhao Wutao, who had worked as a delivery rider for 10 years, woke up at 4:30 in the morning, getting ready for a 5:00 am shift. Zhao generally worked long hours, but his deliveries that day in Beijing’s Fengtai district, southwest of the city centre, were likely to go even longer, owing to the Singles' Day shopping rush ahead of 11 November, popularly known as "Double Eleven."

The day before, Zhao had logged 14 hours of work, rushing from one delivery to another, from 5:00 am to 8:30 pm. On both of the previous days, his manager had sent out a message to the couriers at his hub saying that there were to be no exceptions to the early start time and no one could request leave. Sometime during these two days, Zhao had noticed he was coughing up pink phlegm, but he continued with his deliveries. According to one subsequent account, he delivered as many as 566 parcels in a single shift.

A message sent by a manager at Zhao Wutao’s delivery service company tells workers on 1 November that everyone must begin work at 5:00 am. The next day, they were told to again start at 5:00 am, with no leave requests allowed. Source: Toutiao

At around 8:00 am on 3 November, already several hours into work, Zhao began experiencing chest pain. He went to Fengtai’s Nanyuan Hospital, where a doctor determined he was suffering from severe pneumonia and congestive heart failure. His symptoms included tightness in the chest, shortness of breath, and coughing up blood.

Zhao ignored the doctor’s recommendation that he be immediately admitted for treatment, insisting on checking out. As a migrant worker from Henan, he likely did not have social insurance in Beijing, meaning he would have to pay medical fees out of pocket there. Instead, Zhao said he wanted to travel to his mother’s home in Henan province, where he could recuperate at less expense.

But his health was by this point failing rapidly, and leaving the hospital became impossible. At around 5:00 pm that day, seeing the seriousness of Zhao’s situation, a doctor at Nanyuan Hospital used Zhao’s mobile phone to reach his family. But as his family members were all miles away in Henan, so the doctor urgently contacted Zhao’s employer. He sent an image of Zhao hooked up to medical equipment. The boss apparently thought the message was a hoax. The doctor followed with an audio message:

I am a doctor, and he is critically ill and being treated. He has no family in Beijing. You are his leader, right? We need your company to send someone to the hospital right away!

The doctor provided the address for the hospital, but no one from the company ever showed up. Three hours later, as his family was en route to Beijing, Zhao died of a heart attack. The doctor’s diagnosis was that Zhao’s heart failure had been triggered by overexertion. When Zhao’s family members later reviewed the record of his deliveries through the delivery app, they understood why.

The family found that he had made a staggering number of deliveries in the period leading up to his heart attack, with orders tripling over just several days, from 135 deliveries on 22 October to 566 on 25 October.

The day after his death, Zhao’s account was suddenly removed from the WeChat work group where managers had posted the demand for a 5:00 am start on 1 and 2 November. His account on the app through which he processed delivery requests was also suspended. It was as though Zhao Wutao had never worked as a delivery rider.

Zhao’s sister later told the media that the express delivery company had not signed an employment contract with her brother and had never paid social insurance, which meant filing a claim for work-related injury compensation in Zhao’s case would be nearly impossible. Zhao is not alone in this predicament. Nearly all platform delivery workers across the country face this challenge.

The elusive labour relationship

In cases where a company refuses to file a claim for work-related injury compensation and does not recognise an employment relationship, it falls to the worker’s family to pursue justice. China’s official trade union should be a major avenue for workers and their families. According to Article 17 of China’s Regulation on Work-Related Injury Insurance, introduced in 2004, the union has the right to make a claim for work-related injury compensation on a worker’s behalf.

Had the union attempted to file an application on Zhao Wutao’s behalf, or would they be willing to if the case was brought to their attention? With these questions in mind, CLB reached out in January 2023 to the Dahongmen union in Fengtai district where Zhao worked. The official we reached told us there was no way for his office to file a work-related injury application in Zhao’s case because this had to be done in the platform company’s headquarters, in Shanghai. For this reason, the most his office could do, he said, was to refer the case to the relevant union branch in Shanghai:

With delivery platforms, wherever his company is, that’s where the labour relationship is. If he has this affiliation, then this affiliation means it doesn’t involve us here in Dahongmen.

When CLB asked whether Fengtai district had a service industry union or a general industry union that might take responsibility for Zhao's work injury application, the official responded that the district had neither. And would it be possible for the union office to reach out directly to Zhao’s family to see if there was any way they could help? On this point, the official waved off any responsibility for going deeper into Zhao’s case:

As far as our work unit is concerned, we are just a transfer station for him.

Noting that the Beijing Municipal Federation of Trade Unions had scheduled for the first week of January 2023 a so-called “sending warmth” event, which generally involves face-to-face exchanges between officials and the community, CLB asked the official if his union might be able to include the Zhao family in its planned visits, letting family members at least know the union existed. The official was vague about this, again trying to emphasise that Zhao’s case had no connection to his office:

Sending warmth is something we definitely do. But these are separate matters entirely.

A photo from a similar sending warmth campaign that took place in 2022 in Beijing. Photo: Toutiao

The official recommended that the Zhao family and CLB dial the hotline for the ACFTU at “12351,” which he said would be the quickest way to get help in Zhao’s case.

What actually happens when a request for assistance is relayed through the official ACFTU hotline, which officials insist is the proper channel for communicating with the union?

Hotline, cool reception

Taking the advice of the Fengtai district union office, CLB dialled the 12351 union hotline and provided a full account of Zhao’s case to the operator. Considering the stipulation in Article 17 of the Regulation on Work-Related Injury Insurance about filing for ascertainment of a work-related injury by the union within one year, would it be possible for the union to act on Zhao’s behalf? The hotline operator responded that determinations under Article 17 had to be requested by the enterprise trade union.

But would it not have been possible, CLB asked, for the union, as a body representing the legal rights and interests of workers, to play a more active intermediary role in Zhao’s case by getting the work-injury determination to move along? After all, there would be a police report on Zhao’s case. So the union could easily reach out to local police for details about the case and about Zhao’s family members. And it could contact the family directly about the work-related injury determination.

The ACFTU hotline operator suggested that playing such a role was beyond the union’s authority:

The union does not have the authority to go and contact the police station or the family members. Our office can’t contact other departments and request their assistance.

The suggestion that the ACFTU lacked the authority to directly contact the police seemed odd, considering that the union had worked regularly with other departments in the past. When CLB asked about this, however, the operator was adamant. “You might think we have connectivity with all organizations, but in fact, we don’t,” they explained. “Because we are an organization, and they are a law enforcement agency.”

Finally, CLB contacted the local government in Henan’s Lianhua township, where Zhao’s family resides. The head of the township civil affairs office said on the phone that he was willing to search for Zhao’s family, but that it was possible that they were not registered in his township. However, if a record of them could be found, he said, he would arrange for legal assistance for the family in pursuing a work-related injury determination.

A much-needed “rule of law checkup”

Along with the process of unionisation, there has been a recognition among officials in the ACFTU that more must be done to ensure that the rights and interests of platform workers are protected in practice and that industry players are upholding their legal obligations. In a special publication in May last year, an ACFTU department explored a number of concrete proposals for promoting unionisation. One article on possible initiatives in the city of Rizhao, Shandong province, stated:

[We must] create a strong atmosphere of respect and concern for workers in non-standard forms of employment. First, this means promoting the standardisation of industry behaviour. There needs to be a 'rule of law checkup' for non-standard forms of employment - sorting out the problems that impede industry development, hidden dangers to safety, and the protection of workers' rights and interests.

The details of Zhao’s case illustrate how express platforms are able to circumvent responsibility when it comes to the determination of work-related injury compensation and other obligations. But according to China’s current laws and regulations, it should not be so easy for express companies to escape labour relationship designations that should make them liable in cases like that of Zhao’s.

Zhao’s family has a strong legal basis for defending their right to compensation from the employer. Under China’s framework for establishing labour relationships in the absence of a formal employment contract, other evidence can be used to show a de facto labour relationship. In a separate case study on the truck drivers that transport packages among cities for couriers like Zhao to then deliver to customers’ doorsteps, CLB outlines this process. In another CLB case study involving a food delivery rider, the court found in favour of the worker to establish a labour relationship with the delivery hub. The courier industry and food delivery industry operate under similar models of platform companies, local hubs, and fragment labour relationships.

But what are the solutions? Workers need representation to assert their legal rights, and the union has authority to represent workers under China’s laws. How can the union ensure that work-related injury compensation is available for the families of workers like Zhao? And how can it ensure that companies no longer pressure workers to sign contracts and agreements that circumvent formal labour relationships and responsibility for social insurance?

Photograph: Freer / Shutterstock.com

The recent unionisation drive for platform workers has included outreach to workers, collective industry agreements, and other mechanisms. This is a good start, but these measures have largely failed to address root problems. But most union activities are ad hoc approaches and initiatives, which are largely political displays rather than addressing root problems. In January 2023, for example, the Beijing Municipal Federation of Trade Unions arranged for 78.36 million yuan to be spent on “sending warmth” programs for workers in the city ahead of the annual Lunar New Year holiday. The municipal union stated that this effort was meant to provide assistance to workers and “help solve urgent and practical difficulties.”

Such initiatives may play a role in promoting the image of the ACFTU as a responsive organization, and in the goal of building unions “from the bottom up.” But they do not resolve the fundamental problems so painfully evident in the responses from various union representatives concerning Zhao’s case: that the union is both everywhere and nowhere when it comes to the specific claims of platform workers in distress.

In an increasingly fragmented platform economy, defending a worker’s basic rights and interests often hangs on the fundamental question of affiliation and responsibility. Zhao’s household registration was in Henan. But he worked for a decade as a delivery rider in Beijing, employed ambiguously by a local courier company whose parent company is located in Shanghai.

The union itself seems incapable of sorting through this tangle of associations and seeing its responsibility clearly. If platform workers in distress do indeed think first of the union, will they actually know where to turn, and will the union step up to the task?

Further CLB reading:

- Food delivery rider dies on Anhui mountain, family wins legal battle to establish de facto labour relationship (February 2023)

- What You Need to Know About Workers in China: The Platform Economy (November 2022)

- Holding China’s trade unions to account (February 2020)