In China, a growing number of women workers are joining the gig economy as ride-hailing drivers, food delivery riders, and couriers. In this male-dominated industry, marginalised women workers face discrimination, unequal pay, male-centric algorithmic labour controls, and other gender-specific challenges. Women workers in the gig economy should have special protections to address these issues.

During the annual New Year’s Gala broadcast on China Central Television this year, a song celebrated the industrious working class with this line:

Courier brothers feel right at home when riding on the roads!

On the internet, viewers criticised the song for referring to all workers as “brothers,” which dismisses the work of women couriers, who account for over 20 percent of the workforce.

A screenshot of the performance featured on CCTV’s New Year’s Gala

China Digital Times archived an article analysing online comments from viewers, who pointed out that the song reflects media’s underrepresentation of women working in the gig economy:

“On the national stage, women workers have become totally invisible.”

“The stereotype that women have no place in these industries has been reinforced.”

As CLB has studied, China’s gig economy has rapidly developed and created millions of jobs. However, gig economy workers often lack labour contracts and social security, and they are therefore more vulnerable to poor working conditions, work injuries and wage arrears. In addition to these problems, marginalised women workers face challenges created by male-centric systems that overlook different working experiences based on gender.

The gig economy has attracted an increasing number of women workers

Gender-disaggregated data about workers in China’s gig economy is hard to come by. Scattered documentation largely from the companies themselves provides some sense of the gender ratio of gig workers in the major sectors like food delivery, express delivery and ride-hailing.

For example, Sanlian LifeWeek reported that in 2020 in Beijing, only nine percent of the total workforce of food delivery riders were women, and that proportion rose to over 16 percent in 2021. According to data from Cainiao, a courier service platform, the proportion of female couriers exceeded 20 percent by 2021, which is an increase of one-fifth since 2020. And according to China’s ride-hailing company T3, as of March this year, over 50,000 women workers have joined the company as drivers. This is an increase of 32,000 compared to the same period in 2022.

With over 84 million platform workers as of 2021, the industry is growing. Since at least 2017, economic changes have led to many workers being forced out of the manufacturing and service industries to join the gig economy. The pandemic’s conditions accelerated this trend, and post-pandemic global economic conditions have led to factory layoffs, relocations, and shutdowns. The trend is also fuelled by the growing financial burden on women from rural areas and for women performing unpaid domestic labour to find other ways to support their families.

Marginalised women workers face social discrimination that affects their working conditions

The public perception that physically demanding jobs are not for women or that women are bad drivers leads to gender discrimination and stigmatisation for women at work in non-traditional industries. A 2021 article in the Journal of Chinese Women’s Studies found that female food delivery riders receive judgemental comments on a daily basis, such as: “Why couldn’t a girl find an easier job?”

Photograph: B. Zhou / Shutterstock.com

In a 2022 study of women ride-hailing drivers in China published in Gender & Development, women drivers reported that passengers discriminated against them by leaving negative comments and low ratings, or even cancelling rides because “women are not safe drivers.” These forms of discrimination are not only offensive but affect the drivers’ pay.

The 2022 study also describes how women workers struggle with “highly sexualized cultures in a male-dominated workplace.” Gig workers rely on WeChat groups to communicate with other riders and get updated information about local conditions, but in these settings, women workers are forced to participate in a sexist space. One driver who is a single mother was quoted as saying,

I never shared my photos in the WeChat group full of male drivers. I did not feel safe because those men always talked about dirty sex jokes and sent photos of naked women’s bodies in the group chat.

Even finding toilets can be an unexpected challenge. One female rider noted:

A man can pee practically anywhere, as long as people can’t see him. But for women, it is a problem, especially in suburban areas when toilets are nowhere to be found.

One female ride-hailing driver described how she drank less water and limited her movement to avoid frequent bathroom breaks, especially during menstruation.

Algorithms that are fed gender biased data lead to lower pay for women workers

Platform infrastructure also breeds inequality. China’s platform companies are notorious for brutal algorithms that push workers to their limits to increase corporate profits. The data feeding these algorithms is biased from heavily-male inputs, producing a masculine algorithm that assumes every worker to be male and perpetuates a male-centric working standard.

This male-centric ideal has become an impossible norm for women workers to keep up with, especially given that they are simultaneously expected to bear a disproportionate amount of reproductive labour and domestic care responsibilities. For example, The Paper reported in March 2023 that a migrant woman food delivery rider in Shanghai carried her baby on her back while working day and night, and this was framed as a positive human interest story.

The male-centric standard also leads to a wide pay disparity between men and women in the gig economy. A married woman driver with two children expressed that she wasn’t able to work extremely long hours like her husband, telling researchers:

I could not drive more than 10 hours a day because I had to take care of my kids and mother-in-law. So the quality and quantity of my rides were reduced compared to my husband who drove 16 hours a day.

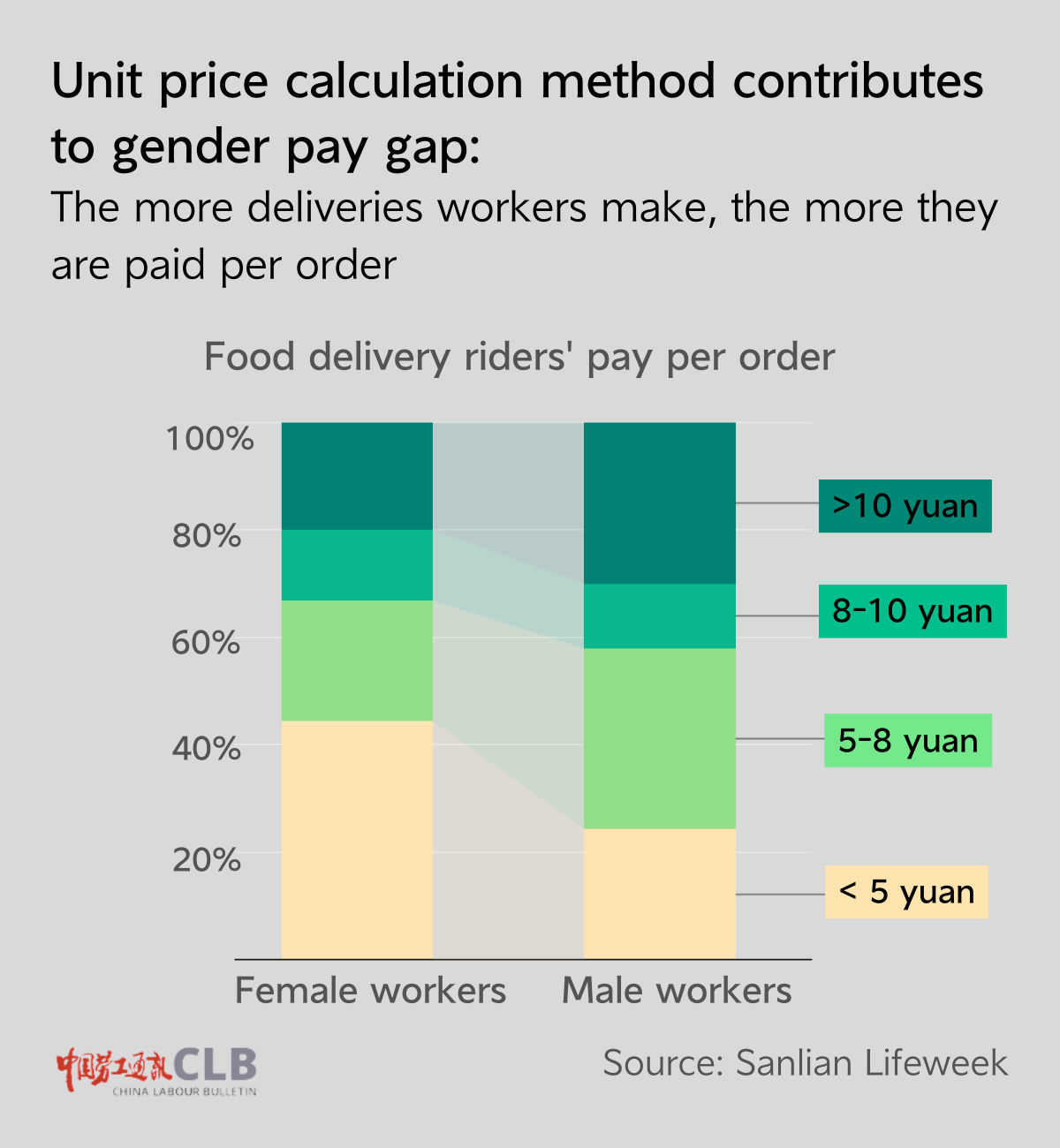

In the food delivery industry, the unit price per order increases with the number of orders delivered. But women workers normally deliver fewer orders than men every month, and are therefore paid less for each order.

According to a 2022 study of women riders, about 44 percent of women are paid less than 5 yuan per order, while only a quarter of men are paid this little. About 20 percent of women riders are paid 10 yuan per order, compared to about 30 percent of men. As a result of these pay disparities, over 60 percent of women riders earn less than 5,000 yuan per month, while about 70 percent of male riders earn more than 5,000 yuan per month.

Women platform workers are also often forced to choose between compromising their health and safety, or earning less income. Ride-hailing drivers who travel to remote areas are rewarded with a bonus of travel points, which increases the quality and quantity of rides they accept, and results in higher income. However, these remote areas are less safe for women. Drivers report fearing assault, especially from drunk passengers. Therefore, women workers tend to avoid accepting these higher-value rides to and from remote areas.

Women platform workers need greater labour protections

Platforms have failed to take women workers’ gendered working experience into account, and this is exacerbated by social discrimination, unfair division of labour in households, and other factors. Companies have a social responsibility to not only create a secure and safe workplace for all workers, but also to design algorithms and working standards that account for all workers’ experiences. The authorities have attempted to regulate platforms’ use of algorithms and the labour conditions of gig workers, but so far this has not resulted in meaningful improvements, let alone from a gender perspective.

China’s official trade union should also take action to understand women workers’ needs and help them negotiate with the platforms. The union at all its levels has women workers’ committees, and these committees should be more visible and active in their role.

Photograph: B. Zhou / Shutterstock.com

In fact, some regional unions have recently touted their activities to benefit women workers in the gig economy. In Zhengzhou, where a provincial food delivery union has been established, the women workers’ committee is focused on poverty alleviation activities. In Beijing, the Meituan union provided women workers with ginger tea, hand cream and feminine products. In Guangzhou, the union has done better at addressing some social factors that exacerbate poor working conditions for women in the gig economy. The union set up women-only rest stations that feature nursing rooms, some counselling support and even some health services.

But from descriptions of these union activities, it is clear that most of these efforts are simply gestures that do not represent the working needs of women in the gig economy. Instead, unions could negotiate with platforms about labour conditions and gender bias in algorithms, and advocate for policy changes to benefit workers of all genders. Courier sisters, food delivery sisters, and ride-hailing sisters deserve better support, protection, and recognition for their labour.

Further CLB Reading:

- What You Need to Know About Workers in China: The Platform Economy (updated April 2023)

- Workplace gender discrimination counterbalances increased maternity, paternity, and parental leave (December 2021)

- Three-child policy and increased maternity leave implementation in the workplace at odds in workers’ experience (March 2023)