In this series, CLB investigates cases of platform workers to raise the specific challenges and potential solutions for how China’s official trade union could represent them, both individually and as a sector. Read more here.

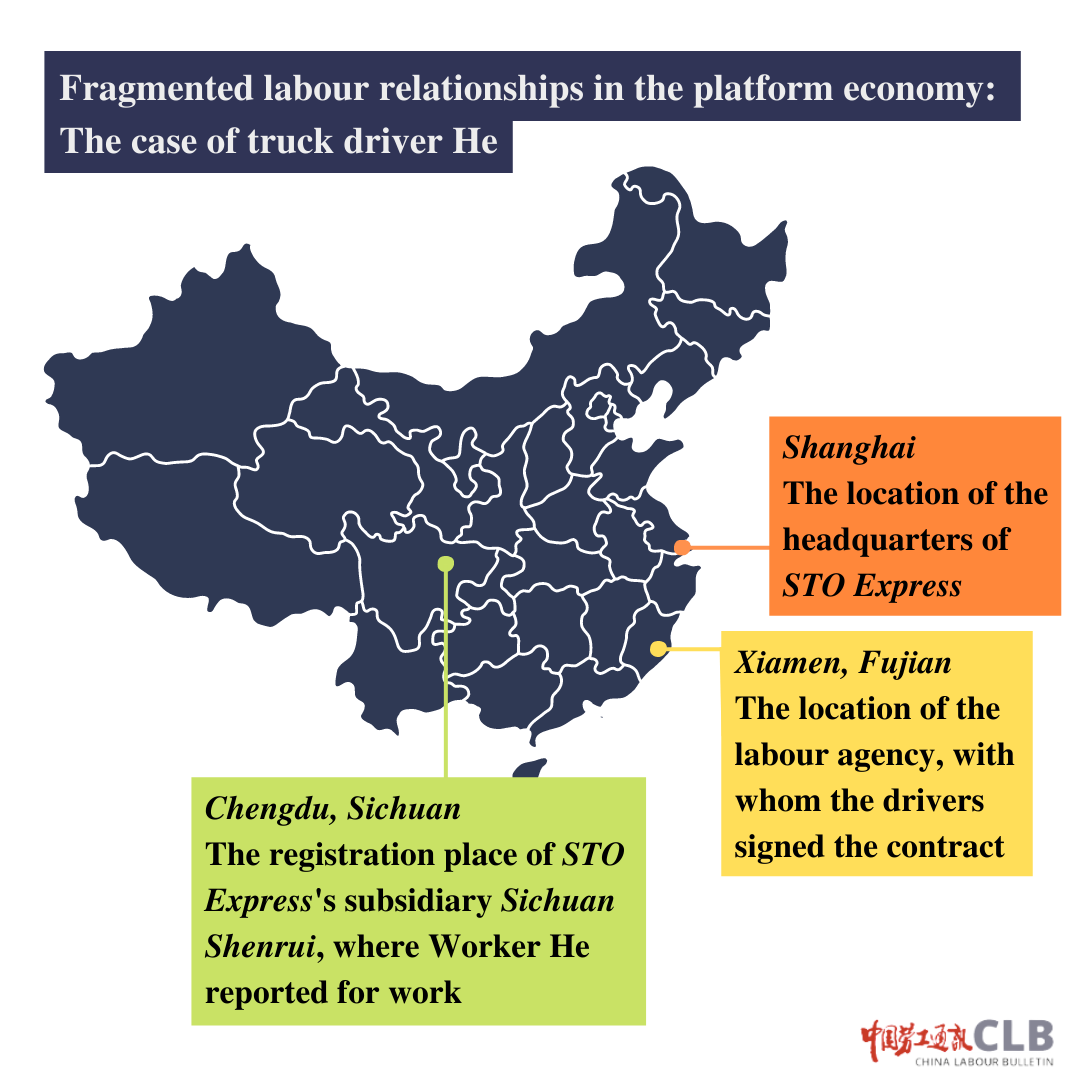

- Two truck drivers for an express delivery company died in an accident in Sichuan, on their way to Guangxi to deliver packages. The platform company is headquartered in Shanghai, and the labour agency in Xiamen. Holding any of these entities accountable for the workplace accident proves a challenge.

- China’s gig economy workers, such as truck drivers who work as independent contractors for platform companies, lack labour protections and have difficulty asserting their labour rights, all while the official trade union has prioritised these workers as part of its “eight major groups.”

On 9 October 2022, a truck under the management of STO Express caught fire and collided with another truck near Zizhong, Sichuan province. The driver, He Xiaoqin, and his colleague were both killed in the accident, right near their hometown in Sichuan while transporting goods intended to reach Guangxi province.

STO Express denied that it had an employment relationship with the drivers, thus avoiding payment of work-related injury compensation to their families.

STO Express is a courier company headquartered in Shanghai. Although the express delivery sector in China is more fragmented than the food delivery industry, which only has two major market players, STO Express is one of five major courier services in China and has a 13 percent market share. STO Express has warehouses, transit centres, and branches across the country.

Photograph: humphery / Shutterstock.com

Is there a de facto labour relationship?

A 2005 notice from the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security provides that evidence and documentation can support the legal finding of an employment relationship, in the absence of a formal employment contract.

In response to the company’s denial of the employment relationship, He’s family wrote that he had worked for STO Express at their subsidiary, Sichuan Shenrui Transportation Service Co. Ltd. (Sichuan Shenrui), for six years. He paid for his own social insurance, but wore the STO Express uniform and collected his salary and commission from the company. However, his contract was with an agency in Xiamen, Fujian province.

On 25 October, when a reporter from Dafeng News called the company, a representative described the working relationship as a “collaboration.” The reporter found that from 1 October, He had signed a service contract that stated that there was no employment relationship between him and the company, and that both parties agreed not to raise labour claims, nor initiate arbitration or litigation.

The contract also required him to lease tools and equipment provided by the company or a third party and bear responsibility for the safety of his person and property. According to the terms, either the company may purchase accidental injury insurance for him or he should purchase it himself. He was responsible for any expenses related to labour, economic, tort, or injury claims.

However, a lawyer from the Shandong Chongzhen Law Firm said in an interview with China Newsweek that because the company managed and arranged the labour, and the labour provided was part of the company’s business, there was a de facto employment relationship between He and the company.

Another driver interviewed said that drivers had no choice but to sign the service contract, saying, “If you don’t accept it, you leave.” This lack of bargaining power on the workers’ side regarding the terms of the contract injects a coercive element to the situation, also pointing in favour of a de facto employment relationship.

CLB’s trade union investigation

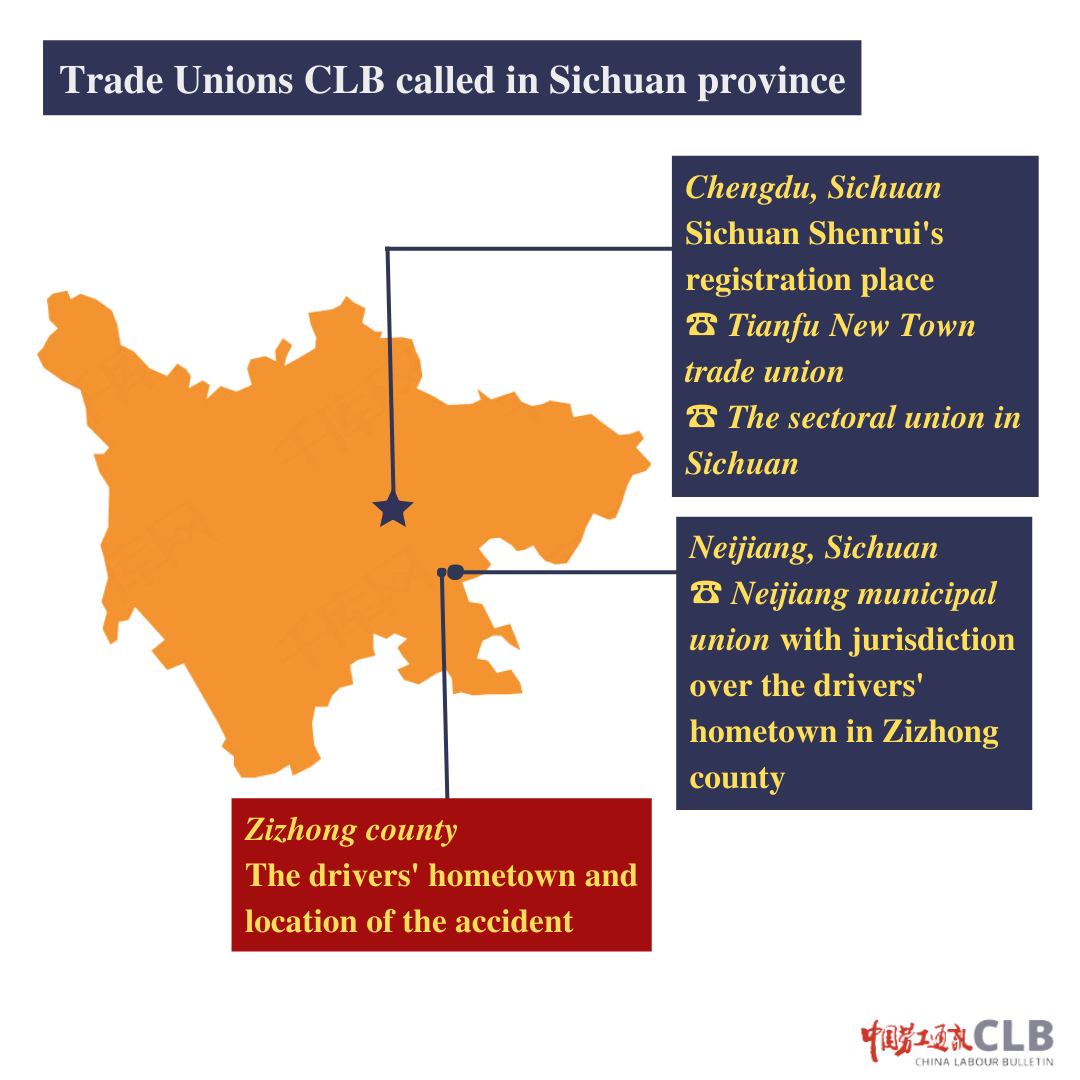

To bring the issue of fragmented labour relationships in the platform economy directly to the attention of China’s official trade union, and to find out whether the union could help the families of the deceased truck drivers, China Labour Bulletin called several different union offices: two levels of the Tianfu New Town trade union, where Sichuan Shenrui is registered; the relevant sectoral union in Chengdu; and the municipal union in Neijiang, with jurisdiction over the area where the workers are from and where the accident occurred.

CLB first called the sub-district trade union in Tianfu New Town and found that the union had not pursued the case at all, after the deaths of two of their own workers.

CLB: I would like to ask whether the family members of the deceased truck drivers have come to the union for help.

Tianfu New Town union official: No family members have come to ask for help as of now.

CLB: China Newsweek and other media have widely reported this; has the trade union seen it?

Tianfu New Town union official: Let me contact the higher level trade union and give you an answer.

CLB: Isn't the union structure based on jurisdiction? Sichuan Shenrui is registered in your territory, on Xinxing Street.

Tianfu New Town union official: Their registered place is here, but their actual business place may not be here.

Instead of reaching out to the drivers’ family members or the company, the official’s response was to contact a higher-level trade union, essentially passing off the case up through the bureaucracy rather than taking any action. When CLB followed the chain by contacting the district trade union office, the person on the other end of the line hung up.

After this, we reached out to the sectoral union. The structure of sectoral unions in China vastly differs from region to region. In Chengdu, the express industry union is organized under the Chengdu Trade Union of Finance and Commercial, Light Industry, Chemical and Textile Workers. We called them to find out if they would take action in this case, in light of the jurisdictional constraints pled by the local union.

CLB: The drivers were killed during the delivery process, and the company does not recognise the labour relationship. Can the express industry trade union step in and directly intervene in the case?

Sectoral union official: Certainly not, the company does not have a trade union, and the problem cannot be solved independently of the company itself.

CLB: Truck drivers rank first among the union’s eight major groups. Doesn’t the trade union have an entry point?

Sectoral union official: The problem is multifaceted.

As part of our investigation, we found that in July 2022, industry representatives, companies, trade unions and workers in Chengdu conducted collective negotiations, coming to a consensus on topics including workplace health and safety. But as we learned from our phone calls, when a work casualty happens, the collective agreement is merely a gesture, and the union takes no action.

Finally, because the workers who died on the job were from Neijiang, CLB contacted the Neijiang municipal union to ask if it could help the families of the deceased workers. In their hometown, we were met with a more proactive response.

The Neijiang union official we spoke to said that they would report the case to the union’s legal affairs department, who would handle the matter. The union official thanked us for providing information and said that they would also reach out to the Sichuan Shenrui company to understand the situation and contact the families’ lawyer.

Trade union must step up and represent workers affected by the challenges of the platform economy

Not only does STO Express not take any responsibility for the deaths of these two workers, but also the more immediate corporation, Sichuan Shenrui, is off the hook unless the union steps in to represent the workers’ families. As for the union, it is content to pass off the incident to other levels and geographies of the union structure, despite its own initiatives designed to increase representation of platform economy workers. Both the corporation and the union can all too easily say that the issue is not of their concern.

The union also made the argument that STO Express and its various branches should form enterprise trade unions to deal with these matters. This line of reasoning is familiar to us, and we note that in the platform economy this kind of logic fails; the enterprise is headquartered in Shanghai, but if workers in other parts of the country tried to register with the union there, they would surely be turned away. Further, the ease and speed with which express delivery companies can open new branches and outlets far exceeds the ability of trade unions to correspondingly expand.

With China’s major express delivery companies in fierce competition for greater market share, they have a greater tendency to outsource fleets to cut operating costs. But by registering subsidiaries in other provinces, it is more difficult for workers and their families to seek redress.

From this case of worker He and his colleague, it is clear that trade unions must take a proactive approach in dealing with companies who shirk their responsibilities as employers. Without union involvement, workers like He will continue to be stripped of their labour rights and their families left without compensation.

Further CLB reading:

- What You Need to Know About Workers in China: The Platform Economy (November 2022)

- Platform truck driver strikes across China result in some changed working conditions (December 2022)

- Holding China’s trade unions to account (February 2020)