China’s top officials have recognised the backpay problem and its effects on vulnerable workers, including migrant workers - particularly this year as the issue is more acute after three years of lockdowns and with Lunar New Year approaching. But workers are no closer to being paid in full and on time, because the top-down system fails at every level and local governments are out of funds. China’s trade union has a role to play in representing workers’ most basic right: being paid for their labour performed.

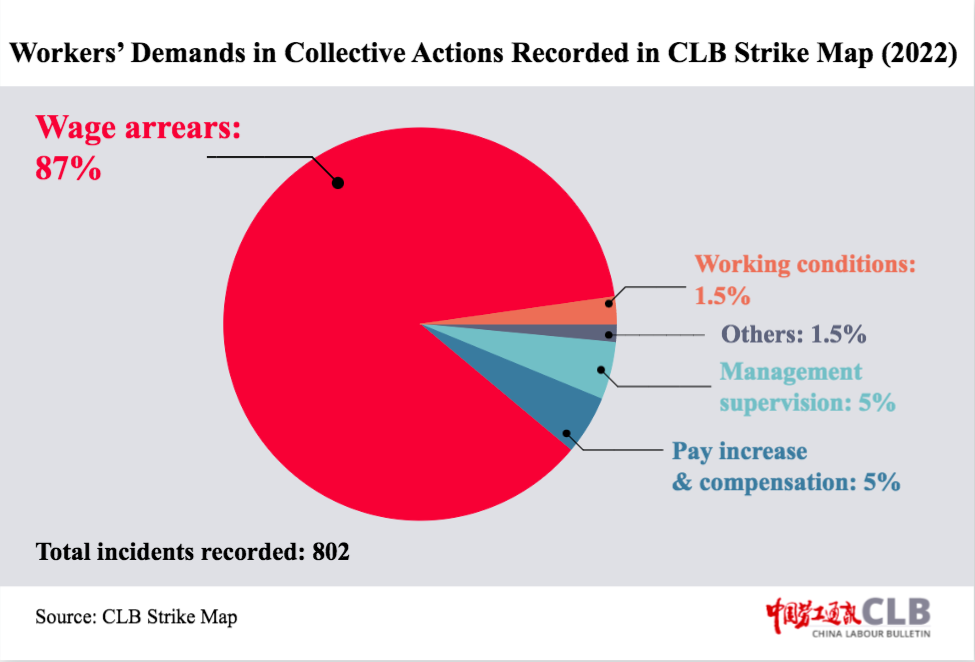

Workers in China continuously take to the streets in protest simply to receive their wages as promised. In other words, these protests are not typically for higher wages or for better benefits, but to be paid at all for their labour. In fact, out of 802 total worker collective actions found in CLB’s Strike Map in 2022, 87 percent involved wage arrears.

Annually, worker protests surge in the weeks leading up to the Lunar New Year, with workers blocking roads, holding protest banners, and even threatening to leap from tall buildings just to be paid what they are owed before returning home to their families for the holiday. This year is no exception, but the level of urgency has escalated after three years of lockdowns, no rise in the minimum wage, high unemployment and a poor overall economy.

China’s Premier and Vice Premier speak out about wage arrears

China’s top officials have admitted that wage arrears are particularly bad recently, despite decades of attention on this problem. Vice Premier Hu Chunhua recognised the effect on migrant workers, specifically:

The problem of wage arrears has rebounded significantly, affected by a number of factors this year. Tackling the root causes of wage arrears for migrant workers will be more complicated.

Vice Premier Hu spoke these words at an annual meeting on the eradication of wage arrears, held on 29 December 2022, and co-chaired by Premier Li Keqiang.

On 4 January 2023, Premier Li told China’s State Council that state-owned enterprises and government construction projects should immediately pay out wages overdue to workers before the Lunar New Year, and he urged local governments to use emergency funds to do so.

Workers protest for their pay while local governments look the other way and police arrest workers

Despite public admonitions at the highest levels of government, officials across China seem incapable of solving the issue, and in some cases, they only make matters worse. Some examples of worker protests illustrate the level of desperation workers are facing and how officials have responded.

Bus drivers in Qingfeng county, Henan province, adorned buses with protest banners in the final days of 2022, demanding 16 months’ worth of back pay. But following their protest, the county government in Qingfeng could only promise to pay a portion of their back pay after 1 January.

Photograph: TonyV3112 / Shutterstock.com

Other workers providing public services, including China’s pandemic prevention workers nicknamed “big whites,” are struggling to get paid by local governments and health care companies as three years of Zero Covid pandemic controls have suddenly ended. Big white back pay protests occurred in major cities across China in December, including Wuhan, Xi’an, Beijing and Shanghai.

One investigation of a big white wage arrears protest in early December revealed that medical workers endured 12- to 15-hour workdays. They were left with three months’ worth of unpaid wages when the boss ran off with the funds.

Workers also face physical violence when they demand their pay. Public anger over abuse of migrant workers seeking wages spilled over online after a viral video showed a group of workers being brutally beaten with iron rods. The workers were demanding back pay owed from working on a construction project in Xiayi, Henan province.

Local authorities quickly issued a statement claiming that the beating incident was simply a quarrel between two businesses fighting over a project. But one online outlet tracked down the workers involved, who refuted the official claim.

A man surnamed Dai explained that he and his five colleagues, all truck drivers, were only a few of the people who were stiffed on the construction project. The workers were engaged to haul construction waste, and the incident occurred when they went to the bosses to ask for their pay before returning home for the new year holiday.

In another incident late last month, police in Linyi, Shandong province, arrested five construction workers for demanding wages in arrears, again sparking online outrage. Police accused the workers of “refusing to go through normal channels” to pursue their wages, and they detained the workers for five days.

The detentions caused one state media outlet to chide local police for not taking action against the offending bosses instead. In a video posted by The Paper, reporter Huang Li for China Sannong Publications, a media outlet under China’s Ministry of Agriculture, responded:

If it’s possible for people to get their back pay through the normal channels, then very rarely would anyone cause themselves trouble to break the law in order to get paid. The price of that is always higher. Considering the harmful effect that wage arrears has on society, we suggest the local government departments focus their efforts on helping migrant workers solve their back pay issues. That’s the point. If there were no wage arrears, then there would be no one breaking the law to get their back pay.

According to CLB’s Strike Map, in 2022 less than two percent of cases resulted in violence against workers, and only one percent resulted in worker arrests.

Even when wages are paid, they are too low for many workers to survive

Not only are workers not getting paid, but their wages are extremely low. After three years of struggling under the pandemic and the minimum wage being frozen, only two provinces - Hebei and Yunnan - opted this month to increase their minimum wage to 2,200 and 1,900 yuan per month, respectively. China’s capital of Beijing did not increase its minimum wage this year, standing at just 2,320 yuan since September 2021.

The minimum wage freezes or recent meagre increases are a boon to struggling employers, but come at the expense of China’s lowest-paid workers.

Photograph: Beersonic / Shutterstock.com

CLB’s Executive Director Han Dongfang believes the state has a responsibility to help workers, but the challenges inherent in China’s governance model are unlikely to lead to a sudden resolution of the problem this time around:

The problem is the system. Even if you push directly from top-down, if you ask officials to correct their ways and take action, they won’t move an inch.

China’s official trade union, however, has a role to play, if only it would become a true, worker-representative organization. Han continued:

If the trade union functions, as they are supposed to be doing, on a regular basis representing workers, whatever problems workers encounter, then workers and bosses can settle problems through negotiation and bargaining, rather than chaos.

The union’s role in representing workers is outlined in China’s labour laws and policies. But the union has not taken up its responsibility to China’s workers in a wholehearted manner. “They claim they have more than 200 million members, but in reality it is not there, it is just about gestures,” said Han.

Further CLB Reading: