The over-concentration of high-quality medical services in China’s big cities means that hospital staff in major urban centres are stretched to the limit while those in under-utilised small city clinics are struggling to get paid.

The South China Morning Post reported last month that China’s more than 2,300 top tier public hospitals were running at full capacity and struggling to cope with patient demands while around 950,000 lower-tier hospitals, community health centres and clinics were suffering from a lack of patients.

Many patients cannot find the medical facilities they need in smaller cities or simply do not trust the doctors there and so they descend on the big city hospitals instead.

Hospital staff in major cities like Shenzhen have to work excessively long hours in highly pressurised and stressful conditions. Many nurses and other frontline staff leave their jobs after a few years because of the intense workload and the very real risk of being attacked by angry patients.

According to a 2015 report by the Chinese Medical Doctor Association, 66 percent of the 146,200 medical professionals surveyed said they had experienced some form of physical or verbal conflict with patients during their career. Last month, the government published a blacklist of 177 people with a history of violence against medical workers but critics say this will do nothing to change to underlying conditions that give rise to violence, namely the high cost and limited availability of decent healthcare.

At the other end of the spectrum, many hospitals in smaller provincial cities, that are dependent on patient fees and drug prescriptions for their revenue, can only afford to pay their staff minimal salaries with few benefits and are sometimes unable to pay at all. So far this year, China Labour Bulletin’s Strike Map has recorded nine wage and social insurance arrears protests by hospital workers in provincial cities across the country.

The two largest cities that saw protests this year were Guiyang on 22 February, where staff were owed at least two month’s salary and social insurance payments totalling more than one million yuan, and in Shenyang, the provincial capital of Liaoning, where there was a wage arrears protest by workers at a plastic surgery clinic on 27 May.

Staff at the Shenyang Lidu Beauty Clinic were owed several month’s salary and social insurance payments but were told by management that they would only get paid after they resigned. Many workers still did not get paid after they left, leading to a protest by more than 20 staff. It was only after an intervention by a local television station that the company finally agreed to pay the staff what they were owed.

There were also protests at several hospitals in the north-eastern city of Jilin, Dazhou in Sichuan, Weinan in Shaanxi, and Bazhou in Hebei.

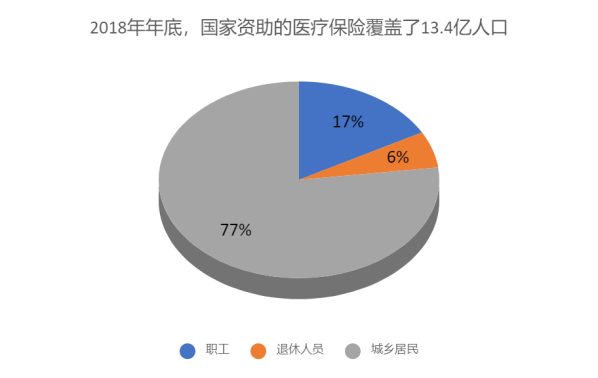

Ten years after the Chinese government launched its massive healthcare reform plan to improve facilities and boost health insurance coverage, the system remains grossly under-funded. China still only spends around five percent of its gross national product on healthcare and there needs to be massive investment in the poorer regions of the country not only to provide decent healthcare for those who need it most but to relieve the pressure on big city hospitals as well.

The government’s new policy goals do include improving the service capabilities of county-level public hospitals, developing family physician-based primary care, telemedicine, and central procurement of essential drugs to reduce costs. However, it is unclear to what extent Beijing is willing to put its money where its mouth is and provide smaller cities and rural residents with affordable and reliable healthcare.