- The worker stabbed three men outside of the Dongguan Best Travel Electronics factory and surrendered to police;

- The incident was most likely rooted in labour dispute, and online comments pointed to the widespread problems of agency labour in China;

- China’s 2008 Labour Contract Law backfired and made agency labour prevalent, leading to increased vulnerability of migrant workers. Agency labour has filled the gaps in the recent manufacturing labour shortage.

On the afternoon of 13 February, a man surnamed Yin stabbed and killed three men outside an electronics factory in Dongguan. The police report describes a “personal grievance,” but a media report indicates the motive was likely a labour dispute involving the use of agency labour.

The murky details of the event have led to speculation and sleuthing online, and competing stories have emerged. But online comments universally condemn the murders while, at the same time, empathise with the plight of factory workers and migrant workers who, all too often, are taken advantage of by bosses, managers, and agency contractors.

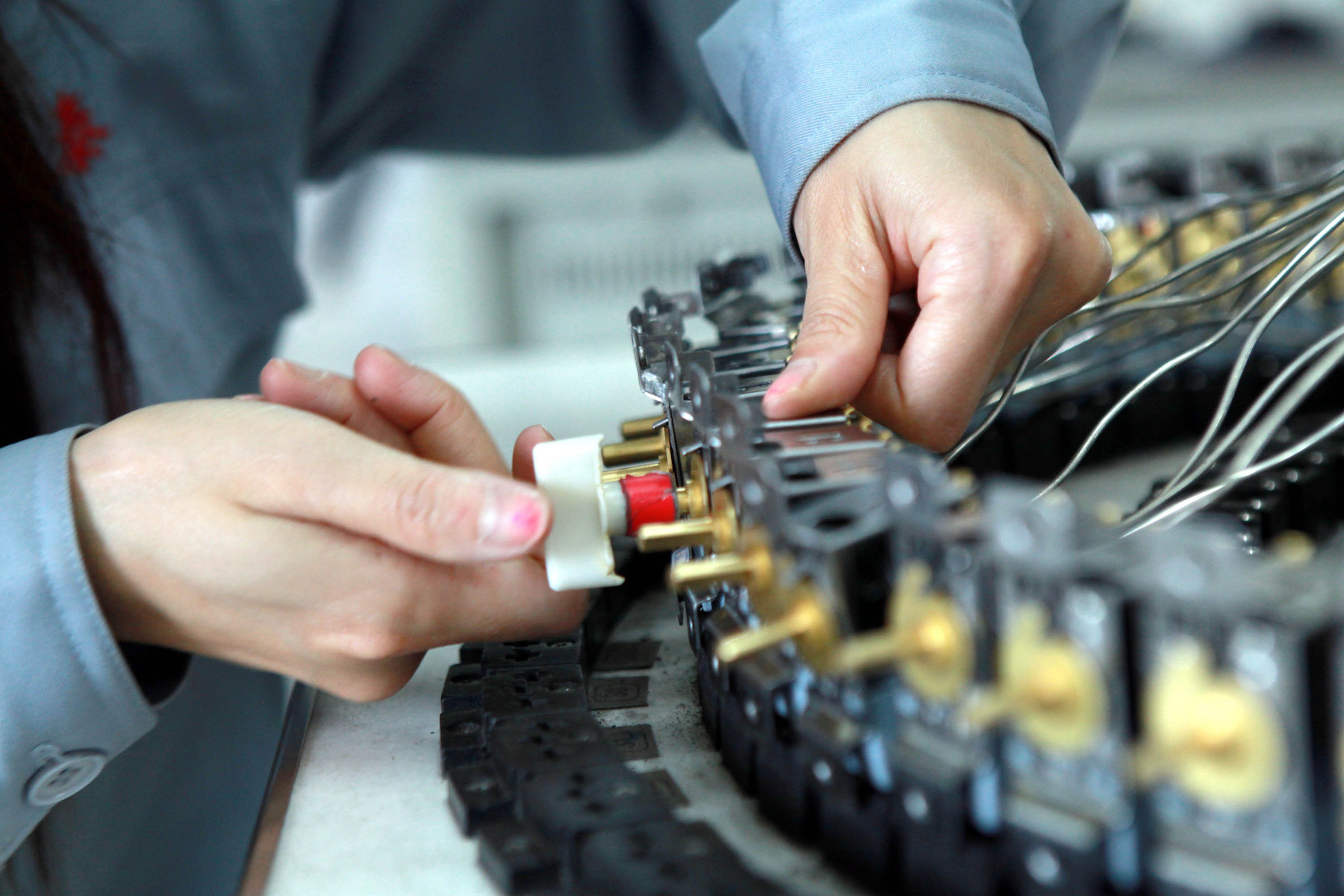

Photograph: humphery / Shutterstock.com

One article stated:

People who have never been in a factory will never understand the discrimination, insults, and working conditions that wage earners receive… Some people just love to bully [migrant workers]. This is karma.

A blogger commented that all too often, most workers don't seek help from administrative or judicial authorities because they know their case may never be resolved:

Their case will turn into a pile of dusty files with the passage of time. The vast majority of them are left unresolved. So those on the reasonable road to get back pay are eventually defeated by time itself. Workers can't afford to wait, because their stomachs will soon be left hungry!

Conflicting accounts of the basic facts, but agreement that worker was pushed to the limit by a labour dispute over wages

A report on the day of the incident from media outlet Chinese Business View quoted factory workers at Dongguan Best Travel Electronic, a Hong Kong-owned manufacturer of travel adapters for export. The workers said that Yin is a migrant worker from Guizhou who had been employed at the electronics factory for three months, between March and June of 2022. The workers identified two of the three stabbing victims as being associated with the factory, one as a supervisor.

Video of the incident was circulated on social media, showing Yin stabbing one man while two others lay injured on the ground. As police officers approach and arrest Yin, he is first seen calmly putting his hands above his head in surrender, and then turning with his hands placed behind his back to facilitate his restraint. One commenter analysed Yin’s actions:

After the police arrived, he stretched out his arms to be handcuffed, which shows that he is not a vicious person, but only that the resentment in his heart would not go away, and in a moment of impulse he caused this horrible disaster.

Other online accounts and allegations about the events identify one of the victims, surnamed Zeng, as a labour contractor; the two other victims, Zeng’s associates, are surnamed Zhang and Wei. One source claims that Yin was owed 4,000 yuan for three months’ work, but Zeng had deducted fees from his earnings, leaving Yin with just 400 yuan.

Another story claims that this was a collective wage dispute. Yin and seven other workers are alleged to have signed labour contracts through Zeng, and they worked at the factory for just a few days in early February. In this version of the story, the workers were cheated through fees levied by Zeng, and Wei and Zhang were hired by Zeng to intimidate Yin.

Last week, leaked security footage from inside the factory offices appears to show Yin approaching a manager with paperwork on 8 February, the week before the stabbings occurred. In the footage, Yin is beaten to the ground.

The intense speculation about the facts and circumstances of the case has led to strongly-worded online comments about the Dongguan stabbing. Many of them speak out against agency labour:

“The urgent task of cancelling labour agencies is the need of the people.”

“For labour agencies, we need to ask, under the 2008 Labour Contract Law, why such an agency should even be established, and why should workers be separated from employers.”

“There is a problem of responsibility transfer here. If the worker has other problems such as safety, the recruiting unit can evade responsibility.”

Fundamental flaws in China’s Labour Contract Law and the rise of agency labour practices

Company records show that Dongguan Best Travel Electronic has previously been party to labour disputes. In 2020, for example, the company lost a labour arbitration case for failing to sign a labour contract with a worker, and upon the worker’s resignation - as laid out in the Labour Contract Law - the company was ordered to pay double the worker’s salary as a penalty. The company appealed the arbitration ruling, and the court upheld the arbitration ruling.

For workers hired through labour agencies rather than directly with the factory, their labour protections are more precarious. Agency labour (sometimes called “dispatch labour”) was not common in China prior to the enactment of the 2008 Labour Contract Law, which requires employers to sign contracts directly with workers to ensure workers' legal protections.

Instead of increasing the rate of formal employment, the law essentially backfired as agency labour became prevalent. To resolve the unintended effect, amendments to the Labour Contract Law were implemented in 2013, and the amendment process involved extensive comments from the public on the draft, including from CLB and other civil society actors.

In 2014, China’s Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security released the Interim Provisions on Agency Labour, which put in place some measures to ensure the principle of equal pay for equal work, that no more than ten percent of a labour force could be agency labour, and that the positions had to truly be temporary, auxiliary, or substitute job positions rather than hiring de facto full-time employees this way.

The problems with agency labour and lack of enforcement of the Labour Contract Law have a disproportionate effect on migrant workers, including those working in construction, sanitation, and manufacturing. The rise of China’s gig economy has also found massive loopholes to China’s host of labour laws and regulations designed to protect workers.

Notably, during the recent labour shortage in China’s manufacturing industry - resulting first from pandemic lockdowns and restrictions on movement, and second from China’s lifting of restrictions and workers contracting Covid-19 and being unable to work - temporary agency labour was widely used to ameliorate the situation. In some instances, these workers protested en masse, claiming that the wages promised by the agency differed from what was actually paid out by the factory.

Further CLB reading:

- Violent wage arrears protest leads to nine detentions (June 2011)

- Collective action gets Guangzhou sanitation workers direct employment contracts (November 2015)

- What You Need to Know About Workers in China: Employment and wages (September 2020)