A 28-year-old ByteDance worker was pronounced dead on Wednesday after collapsing in his workplace earlier in the week. In this month alone, this is the third such case of young workers suspected to have died from overwork.

The ByteDance worker, surnamed Wu, collapsed in the gym at his office in Beijing on Monday evening and was taken to the hospital, where he was treated in the ICU for two days before he was pronounced dead.

Wu's wife, whose name was redacted, told her story on the app Maimai, an anonymous mobile chat forum popular with tech workers. She said Wu often worked overtime and that she was two months pregnant with no job of her own. Wu died leaving the couple with monthly mortgage payments of 21,000 yuan (U.S. $3,322).

Photograph: Chim / Shutterstock.com

Wu's mother also quashed rumours circulating online about a 10 million yuan compensation package from ByteDance for her son's death, saying she and the company had not come to any agreement.

Wu's case is the third reported death linked to overwork in China in February 2022. The second is of a 26-year-old designer at an architecture firm, surnamed Zhao, who was discovered dead in his flat in Shanghai on 15 February after working long hours through the Lunar New Year holiday.

Social media posts and interviews with Zhao’s colleagues revealed that Zhao likely died from overwork. But his company contested whether his death was work related, noting that he did not die while on company property. Zhao's former colleague and friend told the media that although standard company hours were 9am to 6pm, they considered it “early” when they left the office before 10pm.

The third case is of a 25-year-old content moderator on the social media platform Bilibili who died from a brain haemorrhage on 4 February at his office in Wuhan. Co-workers claimed the man had been asked to work extra hours during the Lunar New Year, while the company denied this. Bilibili responded to a flurry of online criticism by saying it would hire 1,000 additional content moderation workers to deal with the team’s workload.

Death from overwork has been a serious problem in China for decades, often leading to tragic battles between bereaved family members and companies who try to shirk responsibility for running workers into the ground. Previous estimates cited in domestic media claim that somewhere between 600,000 to a million or more workers die from overwork in China each year.

Years of discussion about overwork in China have been reignited this week as a result of Wu’s death, with citizens reflecting on whether overwork has become less prevalent after the authorities have promised to crack down and companies have promised to change.

Last year, Wu’s employer, ByteDance - the maker of TikTok - took several moves to reduce working hours. It placed restrictions on overtime requests and reduced mandatory weekend hours, for example. But Wu’s death calls into question whether the company’s work culture has indeed improved.

Discussions of the dreaded “996” working hours system - in which workers, often at tech companies, are expected to work from 9am to 9pm, six days a week - have built popular disdain for unbearably long working days. The popularity of the app Maimai, where Wu's wife told her story, is in part built out of the frustration felt by overworked tech workers and their desire for a space of relative anonymity to share their grievances.

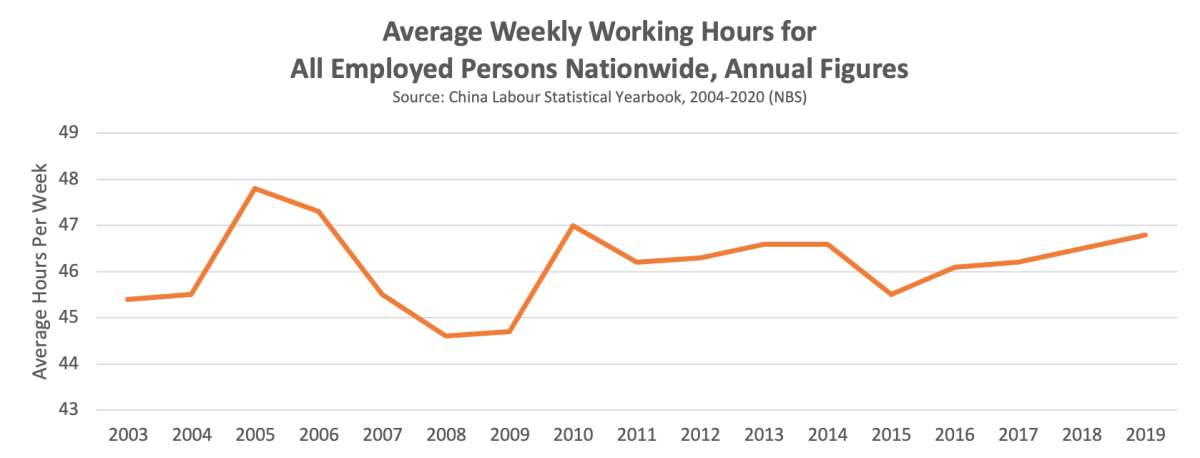

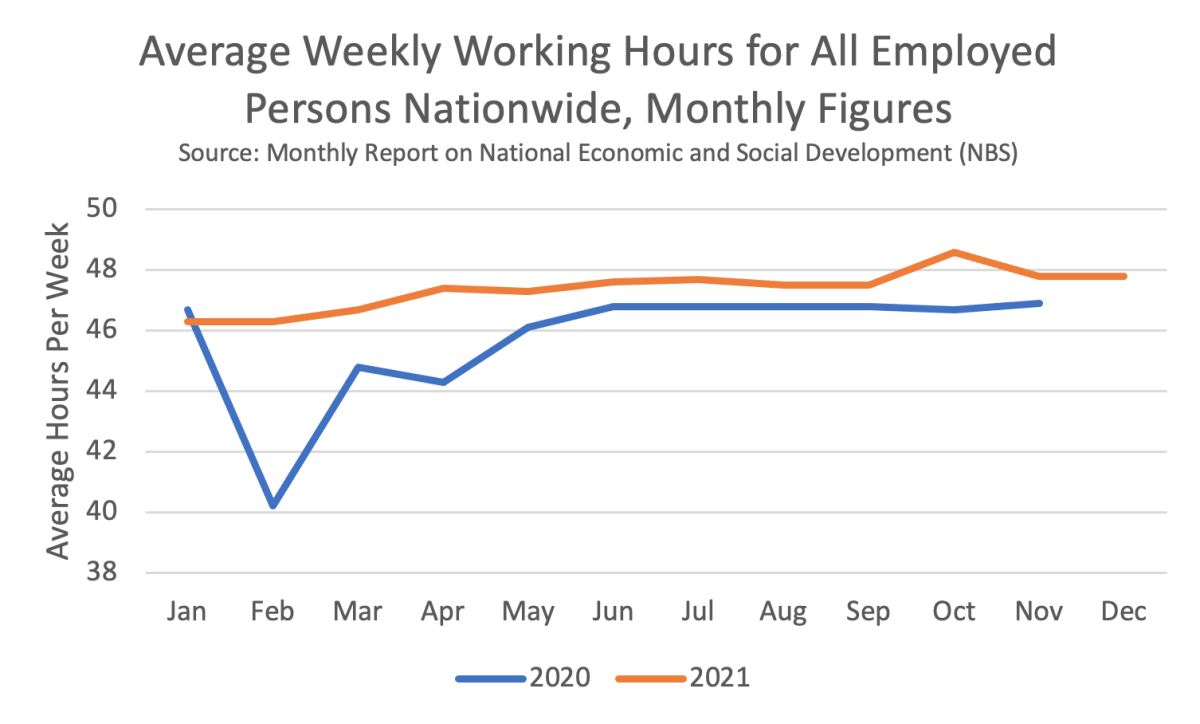

Officials have long known that overwork is climbing to unprecedented levels. Average weekly working hours hit their highest level in two decades of records from the National Bureau of Statistics. Average weekly working hours of employees hit 48.6 hours in October of last year, 8.6 hours longer than the standard 40-hour working week. Working hours have climbed steadily over the past two decades and show no signs of slowing.

Despite a steady stream of young worker deaths linked to overwork, authorities have done next to nothing to change the system. A set of guiding opinions released by the Supreme People’s Court and the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security (MOHRSS) in August 2021 affirm that 996 working practices violate China’s Labour Law, but this is nothing new and there continues to be little to no enforcement.

The guiding opinions, which are not considered legal precedent in China’s civil law system, also included cases on working conditions for delivery drivers, tech workers and others. In each of these cases, workers won their overtime cases against their bosses. But the extent to which this serves as a warning to companies may be minimal. The threat is more like a slap on the wrist.

Just this week, for example, the travel agency Qunar was fined just 3,250 yuan (U.S. $515) for overworking staff members. The local human resources and social security bureau in Haidian district in Beijing caught the company violating overtime rules and enforced this meagre penalty.

China's state-run Central Television published an editorial on Thursday, mourning the death of designer Zhao. But the article left open the question of whether the worker had indeed died from overwork and instead called on companies to respect labour rights and advised workers not to "trade their lives for money" through overwork.

The debate on overwork often follows a generational divide, but China’s young workers overwhelmingly oppose working hours that threaten their very lives. Workers have also taken action to expose the abuse of overtime at their companies. Last year, tech workers organised online to collect data on excessive overtime and expose the 996 systems at specific companies.

Without real workplace organisation in the form of a functioning and representative trade union, workers will have little leverage in forcing employers to become part of the change in China’s work culture.