Photo credit: chinahbzy / Shutterstock.com

Note: China Labour Bulletin recently published our healthcare workers' report: Unprotected yet Unyielding: The Decade-Long Protest of China’s Healthcare Workers (2013-2023). This is the chapter3 of the report. This chapter explains the difference between formal and informal workers, which caused the informal workers to strike and demand equal pay for equal work. It also talks about the problem of low salaries for medical students and graduate students.

The demand for equal treatment and equal pay by healthcare workers was the second most frequent reason for collective actions, with 28 incidents recorded (20 per cent of the total). All of these cases took place in public hospitals, most being tertiary hospitals (16 cases), followed by secondary hospitals (nine cases). Differential employment statuses and compensation packages in public hospitals were the leading causes of dissatisfaction.

Differences between formal and informal workers

The Strike Map has recorded incidents demanding equal treatment since 2014. Ten of the 28 incidents were joint actions by doctors and nurses, and nine were by nurses only (mostly informally employed nurses demanding equal pay for equal work).

Workers in public hospitals in China are employed in three main ways: formal employees of public institutions (事业编制), contract workers (合同制), and temporary workers (临时聘用). Formal employees enjoy a stable job with higher pay and better benefits than contract and temporary workers. Contract workers have more security than temporary workers. In this chapter, “informal” workers refer to both contract and temporary workers.

Caixin Weekly pointed out in an article that the pricing of public hospitals’ services is generally low, so hospitals rely on revenues generated from medicines, consumables, and medical tests. To limit the expenditure paid to workers, hospitals are reluctant to increase staff, or they prefer to hire new staff on an informal basis. The situation of nurses is particularly telling. An article in the People’s Daily (人民 日报) pointed out that in 2016, the nursing service in public hospitals only charged about 10 per cent of the cost, resulting in a situation in which doctors generate revenues directly, while nurses only increase the costs of hospitals. Not only do hospitals refrain from raising nurses’ income, but they also tend to employ fewer nurses to reduce costs. This has led to a large number of nurses having informal employment and protests demanding “equal pay for equal work” by the nurses.

According to the 2010 Report on the Working Conditions of Nurses in China (中国护士从业状况调查报告) (hereafter “the 2010 survey report”) produced by a team of medical scholars led by Zhang Xinqing, informal nurses accounted for more than 30 per cent of all nurses in general and also of 27 nurses in public tertiary top-scored hospitals (三甲医院). These informal nurses were young and received a high-level education. Their work involved all aspects of the hospital, the same as that of formal nurses, and their work could be even more intensive. While they work similar hours in day shifts as formal nurses, their average number of night shifts per month is significantly higher. According to the 2010 survey report, over one-third of formal nurses said they did not have to work night shifts, but only about 20 per cent of informal nurses said they did not.

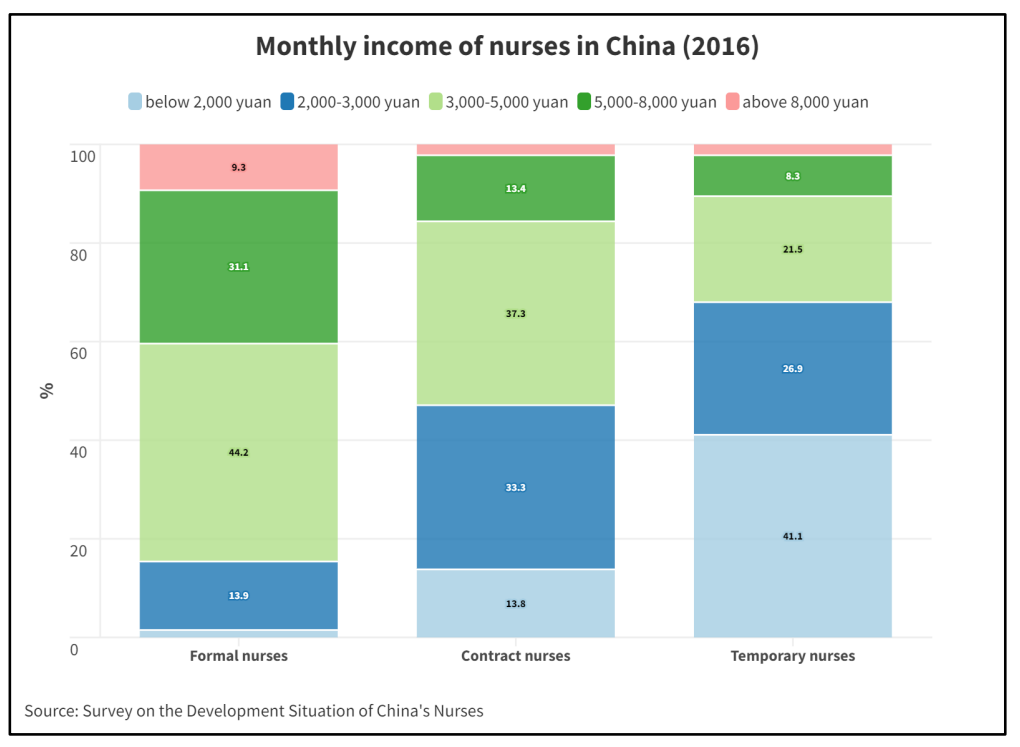

The phenomenon of unequal pay for equal work between formal and informal nurses was prominent, and the salary of informal nurses was only one-third to one-half of that of the formal nurses. In some hospitals, the performance pay for informal nurses was only half of that for formal nurses of the same age, and some hospitals did not pay their share of the social security premium for these informal nurses. Hospitals have also delayed signing long-term contracts with informal nurses or extended their internship periods. It was difficult for informal nurses to obtain formal employment, especially when a clear limit was set on the number of available places. The 2010 survey report found that 57.5 per cent of informal nurses believed that their pay failed to reflect their contributions, which is five per cent higher than that of formal nurses. In a similar survey done in 2016, the difference in treatment was also observed (see figure below).

Also, the 2010 survey report notes that informal nurses had fewer opportunities for promotion. For nurses with seniority between 5-10 years, the proportion of formal nurses with middle ranks (中级职称) was nine per cent, compared to 0.6 per cent of informal nurses. As for seniority of 11-15 years, the proportion of formal nurses with middle ranks was 35.7 per cent, while it was only 11 per cent for informal nurses. In addition, more informal nurses were subjected to patients’ verbal abuse (72.3 percent, 4 percent higher than formal nurses) and physical aggression (16.3 percent, 7 percent higher than formal nurses). Informal nurses were often the punching bag for nurse managers and doctors. An informal nurse complained by saying:

“We are the ones who are often criticized, even when we are right. When a formal nurse makes a mistake, the head nurse turns a blind eye.”

As a result, informal nurses fight for equal treatment. The actions collected in the Strike Map were mostly concentrated in tertiary hospitals, probably because informal workers felt that these hospitals were better equipped to achieve equal pay for equal work.

A protest in Jianli, Hubei

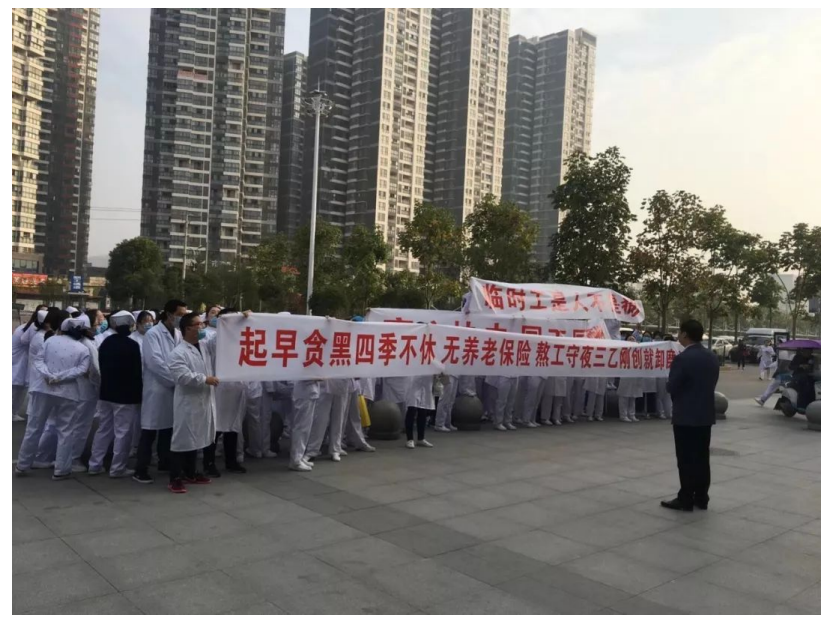

In 2018, informal workers at the Jianli County People’s Hospital (监利县人民医院) in Jingzhou, Hubei province, went on strike, holding slogans such as “Temporary workers are human beings not dogs” and “Equal pay for equal work”. Protesting workers complained that informal workers were treated less favourably but had a heavier workload. One worker said:

When things go wrong, contract workers are forced to go forward with overtime every day, disregarding our families or children. When it comes to wages, the gap between formal and informal workers is like between heaven and hell.

Formal workers’ monthly base salary is 4,000-5,000 yuan (U.S. $571 - 714), while that for informal workers is only 1,000 yuan (U.S. $143). Including performance pay, the highest monthly income for informal workers is less than 4,000 yuan, and the lowest is less than 2,000 yuan (U.S. $286). Employees accused the hospital of falsifying documents to experts (advising on hospitals’ finances) at its development, claiming high performance pay packages for informal workers. The hospital could then cut informal workers’ monthly performance pay by 30 per cent based on experts’ advise.

The protesting employees also said that they had been without social insurance for a long time. One worker said:

“Can anyone imagine any public institutions that don't have pensions? I remember when I first came to the hospital, the hospital said, ‘You are all still young. You don’t need to buy a pension now,’ but we have worked for so many years, and some colleagues have worked for more than 10 years. Are we still young? Do we not need a pension?”

Photo: Temporary/contract labour strike at the People's Hospital in Jianli County. Photo credit: Web posting, China Labour Bulletin archive.

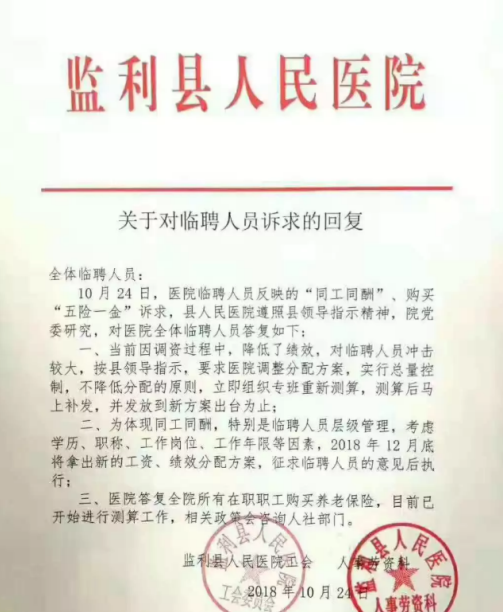

On 24 October 2018, the hospital’s enterprise union and personnel and labour section issued an announcement, saying the hospital will develop a new plan for salary and performance pay allocation and implement it after consulting the informal staff. The hospital also said it would purchase pensions for all employees.

Photo credit: Web posting, Chinese Labour Bulletin archive.

After years of violating the law by not making social insurance available for its informal staff, the Jianli County People’s Hospital agreed to pay pensions only after workers protested. However, the hospital did not promise to pay for other types of social insurance or address making past payments on social insurance, meaning that workers lost out on this legally entitled benefit.

Protests by informal workers were not limited to Hunan but sprang up nationwide. For example, on 19 July 2017, nurses at the Yan’an People’s Hospital (延安市人民医院) in Shaanxi province protested for equal pay for informal nurses. They pointed out that informal nurses made up 80-90 per cent of the nurses in the hospital. In addition to pay disparity and the lack of social insurance, informal nurses were not allowed marriage and funeral holidays, received no reimbursement for family visits or maternity leave, and the hospital implied that they could not take paid annual leave after having taken maternity leave. Workers cited laws that prohibit the hospital from treating informal workers in this manner. They demanded that the hospital fulfill its legal obligations, including signing labour contracts, paying for social insurance, and making proper vacation arrangements. They also demanded equal pay for equal work and that the hospital recruit nurses to share excessive workloads. The unions’ websites show that the Yan’an City Federation of Trade Unions (延安市总工会) and the Shaanxi Provincial Federation of Trade Unions (陕西省总工会) did not work on these issues between 2017 and 2018.

The 2010 survey report points out the reasons that informal nurses suffered from discriminatory treatment. In addition to the fact that the quota for formal employees in public hospitals has not been 31 adjusted for a long time and regulations such as the Nursing Regulations (护士条例) do not require informal nurses and formal nurses to receive equal pay for the same work, the lack of a collective bargaining mechanism prevented nurses from raising their grievances. The enterprise unions in hospitals also tend to yield to the views of the leaders of medical institutions and dare not involve themselves with the issue of informal nurses’ labour rights.

Medical students in residency training

At the end of 2022, nine protests were initiated one after another by medical student residents (规培生). After pandemic prevention measures were dropped, hospitals asked resident students to help in hospitals due to staff shortages because of the massive increase in infections in the population. This situation led to students protesting against unequal pay for equal work. Students also requested schools or hospitals to provide protective materials and ensure work safety. Another demand was “voluntary return” (自愿返乡). It was the end of the semester at the time, and most university students could take leave and return to their hometowns. Medical students thought they should have the right to return to their hometowns too.

In addition to these strikes, the CLB Calls-for-Help Map also collected four cases. One of them was the sudden death of Chen Jiahui, a resident at West China Hospital of Sichuan University (四川大学华西医院). According to a report by Caixin, the day before his death, he was working in a busy paediatric surgery department. Later, he fainted in his dormitory, was rushed to the hospital, and tested positive for COVID-19 at the time of his death.

Picture: Resident students from West China Clinical Medical College of Sichuan University protested, and school board members were there to respond. Photo credit: 李老师不是你老师.

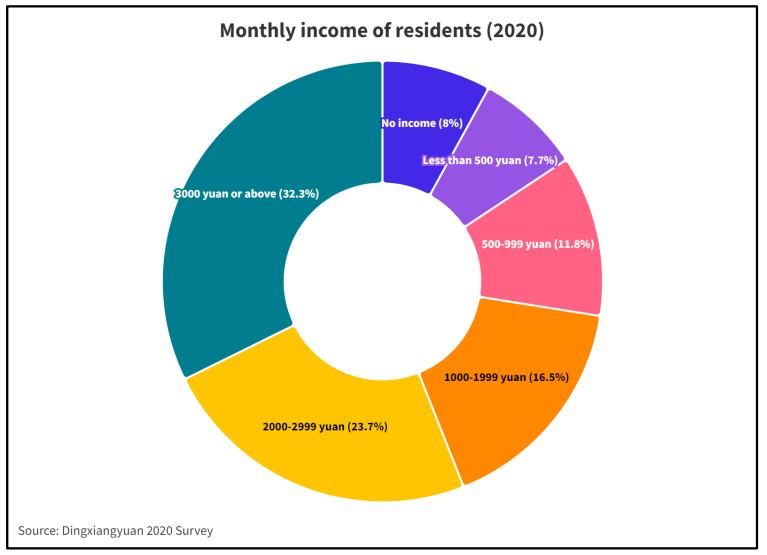

The residency program in China, known as “standardized residency training” (住院医师规范化培训), requires medical school graduate students to spend three years in a hospital to receive systematic clinical training before practising as doctors. The students are not regular hospital employees and do not receive a normal salary during this mandatory training period. In 2020, a survey of 3,020 residents found that nearly 30 per cent said they earned less than 1,000 yuan (U.S. $143) per month, with eight per cent saying they had “no income” during their training period. Only about 30 per cent reported earning more than 3,000 yuan (U.S. $429) per month.

The wages of medical residents are usually not enough to support a living. According to a report by Badian Health News (八点健闻), a young resident in training in the capital of an eastern province said that his income was about 1,300 yuan (U.S. $186) a month. The average wage in his city exceeded 5,000 yuan (U.S. $714) , and the minimum wage stipulated by the government has also exceeded 2,200 yuan (U.S. $314).

In 2014, China officially launched the resident training system, and the state subsidised the medical residents at 20,000 yuan (U.S. $2,857) per person per year. At that time, this amount was similar to the national average disposable income of urban residents in 2014, Badian Health News noted. However, this one-size-fits-all policy fails to consider China's vast regional differences. By 2021, the gap between the subsidy for medical residents and the disposable income of urban residents was clear. In 2021, the subsidy for residents will be 24,000 yuan (U.S. $3,429) per person per year, compared to the national average disposable income of 47,412 yuan (U.S. $6,773) per urban resident. Although provincial governments and hospitals also provide certain subsidies, there are huge differences between regions and hospitals.

In late 2022, the sudden relaxation of pandemic prevention measures led to a surge of positive cases. A large number of medical staff were infected with COVID, resulting in a severe shortage of personnel, with some healthcare workers even required to work while ill. A report by Dingxiangyuan (丁香园) said that more than half of the staff in the fever clinic of a tertiary hospital in Beijing were medical students. A doctor at the hospital said:

“The care workers have run away, and the students have to manage patients’ hygiene as well as feeding them. But there’s no way around it. Staffing is just too tight.”

During this phase of the pandemic in late 2022, a number of medical colleges have demanded that residents return to their jobs by threatening them with not being able to sit for their final exams, causing a wave of protests. A report from Labour Info China (工劳小报) said that most protesters were postgrads studying for specialist master’s degrees (SMD, 专业型硕士研究生) and undergoing training. This group of residents was particularly underpaid even when compared to other residents [3]. Citing their status as students, hospitals do not pay them a salary and only give them a monthly stipend ranging from 200-1,000 yuan (U.S. $29-143) while assigning them the same jobs as other residents and even doctors. Some protesters questioned:

“What is our status? If we are still students, we have to be responsible for our own health and demand to return to our hometowns; if not, we should be given the appropriate status and treatment.”

Due to intense competition among medical students to enter China’s top-scored tertiary hospitals (三甲医院), students usually have to obtain postgraduate degrees (even postdoc degrees) to stand a chance. The SMD programme is a popular choice among medical students, as it allows students to obtain a master’s degree and complete residency simultaneously within three years. Another similar programme is clinical postdocs (临床医学博士后), through which doctoral graduates can obtain a postdoc degree and complete residency in three years. While SMD students suffer from low salaries, clinical postdocs receive generous state subsidies for the first two years. However, from the third year onwards, clinical postdocs could face problems similar to those of SMD students (especially with the pandemic).

In 2022, conversations in the “Clinical Postdoc Group” of the First Affiliated Hospital, Sun Yat-Sen University (中山大学附属第一医院) were circulated, in which a surgeon criticized the low pay (5,000 to 8,000 yuan/ U.S. $714-1143 per month), lack of formal employment quotas, and even wage arrears. A report by Badian Health News points out that postdocs can receive a state subsidy of 284,000 yuan (U.S. $40,571) per year before tax for the first two years, but after that, the subsidy is cut and they only receive the wage level of residents. An interviewed M.D. said: “The top hospitals used to operate reasonably well, but with reduced revenue from the pandemic and other events that exacerbated the problem, postdocs are likely the first to see their salaries squeezed. Starting a postdoctoral program in clinical medicine is not something any hospital can do.”

Other than unfair pay, residents and postgraduate medical students have also suffered from a lack of labour rights as a whole. In 2020-2021, a healthcare worker Liao sued a hospital for violating labour laws during her residency in 2014-2018. In 2014, the hospital had promised in a written agreement to sign a labour contract with Liao, a medical college student then. In 2015, Liao reported to the hospital after graduation but signed the “standardized training agreement for residents” rather than a labour contract. During the period of residency, Liao became pregnant. At the end of residency in 2018, the hospital did not retain Liao or renew her contract. In 2020, Liao sued the hospital, demanding it to pay double wages for not signing a written labour contract, unpaid leave wages, unemployment insurance, and compensation for illegal termination of labour relations. Liao’s demands were based on China Labour Law (劳动法) and China Labour Contract Law (劳动合同法). Still, the court rejected her because the two parties only had a residency agreement but did not establish a labour relationship. It can be seen that resident students undergoing training are excluded from the labour status and the relevant protections.

If residents and medical students were represented by their own labour unions and could communicate with the hospital management and relevant government departments such as the National Health Commission to fight for their official labour status and corresponding treatment, their labour conditions would improve. They would not have been so resistant to the hospital’s announcement to return to work in late 2022 and felt that they could only get a response if they voiced their demands through collective action.

Unfortunately, although trade unions have occasionally acknowledged the concerns of medical residents, they have not made much effort to improve their treatment. Liao’s case was actually published in the China Worker Website (中工网) (the news website of the ACFTU) in an article entitled “Can medical graduates who participate in residency have their labour relationship confirmed?” The website only reported on this case but did not question the court’s statement or discuss whether the treatment of students undergoing training is reasonable.

To be continued.

Download the full report as a pdf here.

[3] Other residents include medical graduates and doctors sent by hospitals to undergo training.