An online discussion and trade union response to an unverified, viral workplace rant show that illegal overtime work and lack of managerial boundaries is a shared work experience in China.

Don’t ever message me or call me after regular work hours. Don’t @ me here in this chat. This whole time, this group is just for colleagues to share things and chat, but you made it a group for work, shame on you.

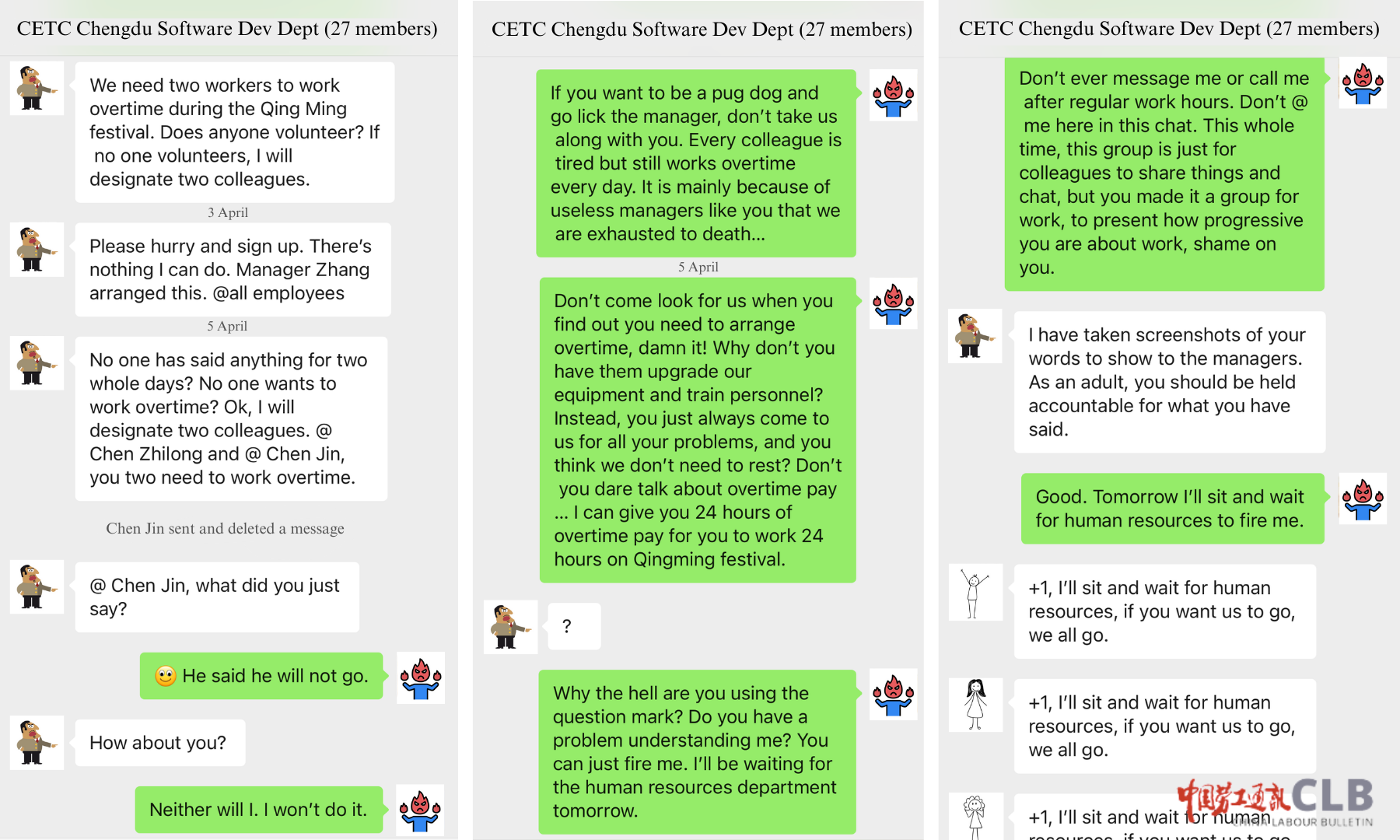

According to screenshots of a WeChat group message interface reposted online and shared millions of times, a tech worker sent this strongly-worded message to his manager on the eve of this year’s Qingming Festival, a public holiday for gathering with family to sweep the graves of ancestors.

CLB’s translation and rendering of chat messages shared online

According to the internet sources sharing the post, the worker, Chen Zhilong, was a contractor of China Electronics Technology Group Corporation (CETC) in Chengdu, Sichuan province. CETC is a state-owned company and China’s third-largest electronics and IT company. Chen worked in CETC’s software development department, and he and his team had been logging about 100 hours of overtime per month when they were asked to work overtime on the public holiday, sparking the chat messages.

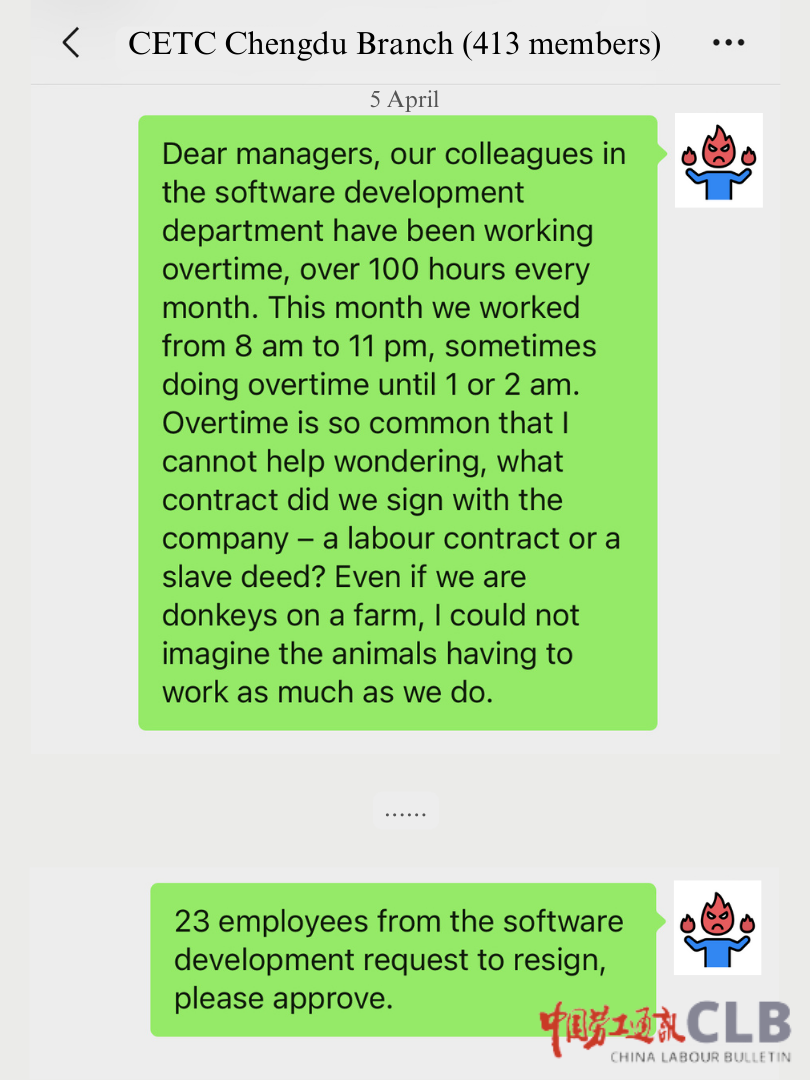

After the messages in the small team group chat, Chen Zhilong took this grievance to another work chat group with over 400 members, reporting the excessive overtime and that the whole team wished to resign.

CLB’s translation and rendering of chat messages shared online

When the story started circulating online in April 2023, the official trade union reacted quickly. Both the Chengdu municipal union and the Sichuan provincial union stated that they would immediately investigate this case and protect workers’ rights if they found any infringement on working hours by the employer. The unions even promised to directly intervene at the SOE and open a discussion on collective negotiations to resolve workers’ complaints. At the same time, the union stressed that it preferred to resolve the incident without all the public attention on the case.

The fact that CETC is state-owned is relevant to the labour rights and workplace norms there. For example, employees of SOEs generally have labour contracts, standard benefits, and work regular hours. Further, most SOEs early on established enterprise unions affiliated with China’s official union, making it more straightforward for the official union to intervene and respond to incidents. Therefore, the allegations of significant overtime and heavy reliance on contractors at an SOE are both surprising, warranting the public reaction and swift response by the union.

The chat messages that went viral, however, have not been proven authentic. CETC claimed the incident was false and defamatory. The Sichuan provincial union walked back its earlier statements and told The Paper that the incident is real, but it happened a year prior and in a different city. And the Deyang city police station in Sichuan province announced that the story was fabricated by Chen Zhilong who was retaliating against CETC for not employing him. The Deyang police reported that Chen lives in their jurisdiction, and they detained him for fabricating the WeChat messages.

Internet sleuths closely analysed the screenshots and speculated on the incidents. Some users agreed that the messages were suspicious, but others wondered why Chen would use his real name if he were fabricating the story.

In China’s information environment, perhaps we will never know the full story. But what is clear is that citizens resonated with the emotions and reactions of Chen and his colleagues in the group chat.

A People’s Daily commentary recognised that perhaps the story is untrue, but what is genuine is the overwhelming resentment white-collar workers feel toward their managers against the abusive overtime requirements at China’s tech companies. Workers got a thrill that Chen Zhilong could say what they had always wanted but never dared to: no more overtime, and no more managers who disrespect employees’ working hours.

Photograph: Chim / Shutterstock.com

Major tech companies have been notorious for “996” working hours - starting at 9 am, ending at 9 pm, and working six days a week. Most workers feel they have no option but to comply. The 996 culture has been identified at the highest levels as unlawful, but few moves have been made to end the practice and enforce the maximum of 40 hours per week plus no more than 36 hours monthly of overtime stipulated in the Labour Contract Law. In fact, a company must follow a consultation procedure:

The enterprise may extend an additional working hour after consulting with the trade union and the employees, and must not exceed three overtime hours per day, or 36 hours per month, even where there are special needs to extend working hours. (Art. 41)

In late 2020 and early 2021, a series of deaths from overwork at China’s top tech companies received widespread attention. E-commerce platform Pinduoduo saw two sudden deaths in a span of ten days. First, a 22-year-old employee surnamed Zhang, died in Urumqi in late December 2020 after working past midnight. She collapsed while walking home with colleagues at 1:30 am. Then, a Pinduoduo engineer jumped to his death in early January 2021. The worker, surnamed Tan, had just graduated from Sichuan University in 2020 and had been working at the company headquarters in Shanghai for six months when he suddenly requested leave and flew to his family home in the southwestern city of Changsha, where he passed away.

In February 2022, the deaths of three young white-collar workers received online attention. A 28-year-old ByteDance worker surnamed Wu was pronounced dead after collapsing in the gym at his office in Beijing and was treated in the ICU for two days before he was pronounced dead. A 26-year-old designer at an architecture firm, surnamed Zhao, who was discovered dead in his flat in Shanghai after working long hours through the Lunar New Year holiday. And a 25-year-old content moderator on the social media platform Bilibili died from a brain haemorrhage at his office in Wuhan. Testimony from these workers’ family and friends corroborated the stories of intense overtime and high-stress work environments.

These periodic clusters of incidents and official reminders for employers to follow China’s labour laws are not enough to stop such practices. In fact, white-collar workers are increasingly identifying with the gruelling conditions of the blue-collar workforce, such as by calling themselves “labourers” (打工人).

Photograph: humphery / Shutterstock.com

The first generation of migrant workers endured excessive overtime in China’s manufacturing industry to earn overtime compensation on top of their regular wages, but China’s younger generation is unwilling to give their time over to their employers. Younger workers in China may have a higher educational background and better bargaining power to resist unfair working conditions and unlawful employment practices, but their widespread experiences speak to a different reality.

Without avenues for worker organizing and effective trade union representation, most workers simply endure, and the most they can do is cheer for underdogs, as Chen Zhilong represents. All employers, whether state-owned or private enterprises, should face adequate enforcement of China’s labour laws.

The quick action by the Chengdu municipal union and Sichuan provincial unions is encouraging and should be a model response for other unions in China to defend workers’ rights. But more can be done than emergency response after violations are reported. Workers need active representation for their interests, before rights are violated, and the union has such bargaining power to negotiate with employers on workers’ behalf to ameliorate illegal overtime.

Further CLB reading:

- White-collar workers aggregate data on their long working hours (October 2021)

- China’s toxic work culture under fire again in Beijing (March 2021)

- Employee deaths put China’s tech sector under further scrutiny (January 2021)