Waan* is an outsourced sanitation worker in Hong Kong who tested positive for Covid-19 at the end of February. Nearly HK $7,000 was deducted from her salary during her isolation period. Although the Hong Kong government recently passed a bill amending the Employment Ordinance to ensure workers are paid sick leave for complying with pandemic-prevention requirements in Hong Kong, the bill is not retroactive.

Waan, who is from Thailand, was far from the only person in her line of work to find herself out of pocket in Hong Kong’s deadly fifth wave of the Covid-19 pandemic. The Hong Kong Federation of Asian Domestic Workers Unions (FADWU) and its affiliate, the Thai Migrant Workers Union (TMWU), fielded many requests for help but came up against long-standing labour issues in Hong Kong: labour rights are not adequately protected under the outsourcing system of sanitation workers, foreign and migrant workers face language and literacy barriers, and the law-making process is slow to respond to workers’ immediate needs.

Freshly cleaned trash bins are stacked in a sanitation station, ready to be placed back on the streets of Hong Kong

Waan works six days a week and holds two street cleaning jobs outsourced by the government’s Food and Environmental Hygiene Department (FEHD). She works her first shift in one district, and then has one hour to get to a second district where she works another full shift for SC Johnson Cleaning Services Co. Ltd. (SC Johnson). Her job is difficult, not only conducting regular cleaning tasks but often deals with full rubbish bags inconsiderately tossed directly onto the pavement. She earns $11,935 a month from her second job that gave rise to her labour dispute.

Many workers from Southeast Asia come to Hong Kong on foreign domestic worker (“helper”) visas. In 2019, before the outbreak of Covid-19, the number of domestic helpers reached 399,000. The majority of these workers come from the Philippines and Indonesia, meaning that Thai domestic workers have fewer resources available to support them.

The average wage of foreign domestic workers is $5,144, with the minimum wage set at $4,630, and they are required to live under the same roof as their employer. Unlike other immigrants to Hong Kong who are eligible for permanent resident status after seven years, foreign domestic workers cannot obtain permanent resident status based on length of stay. However, those who marry Hong Kong residents can obtain dependent visas and find jobs other than domestic work. But most, like Waan, need more than one job to make a living.

As a requirement for her employment, Waan was tested for Covid-19 frequently. On 21 February she tested positive and received a message in both Chinese and English asking her to isolate from 21 February to 6 March. Waan cannot read either language and didn’t realise she was infected until she received another message on 24 February.

She began a 14-day isolation period, but still had a cough on 9 March when the period was over. A doctor issued her a medical leave certificate, and the foreman at work told her she could return to work if rapid tests returned negative results on two consecutive days.

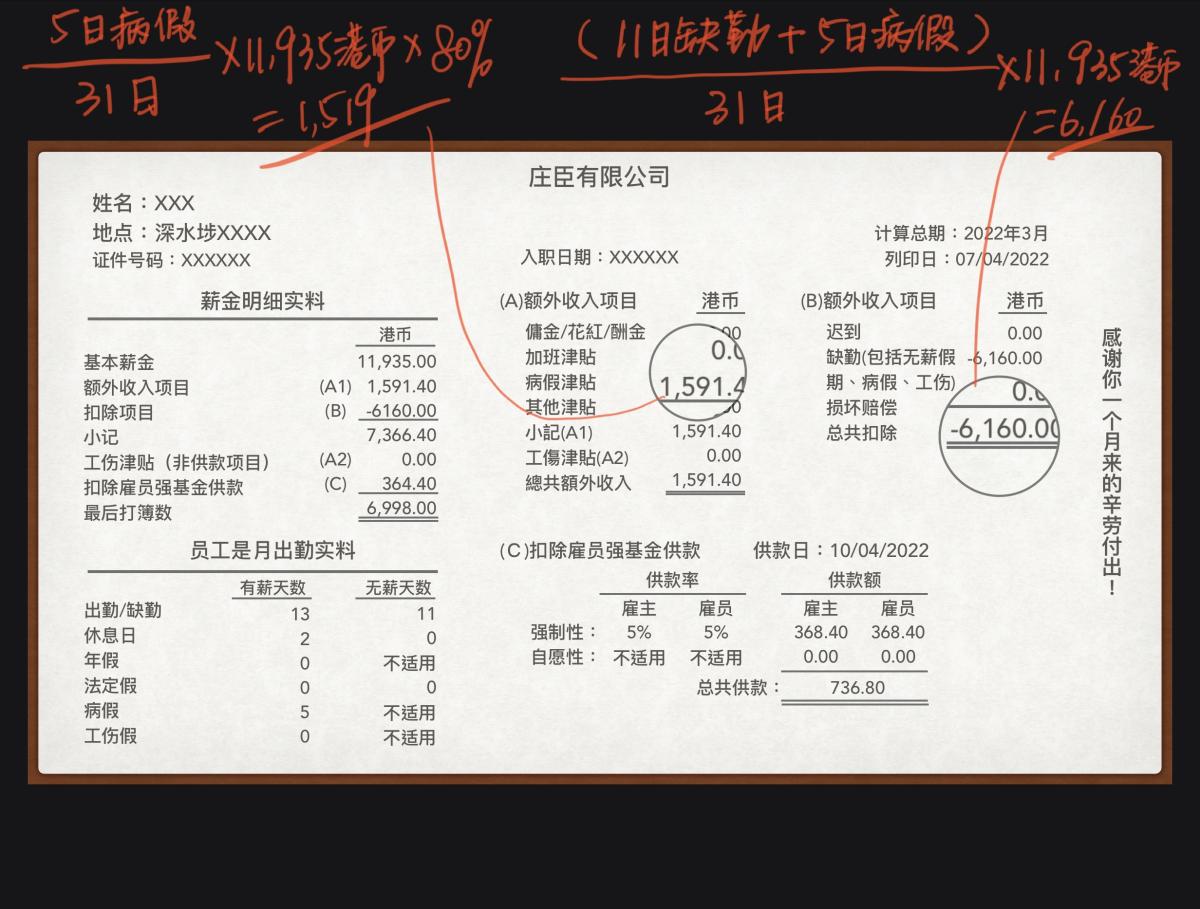

Waan later found that she was not paid for the time she was in isolation and saw that $6,160 was deducted on her payslip. The company recorded her absent for 16 days, five of which were considered sick leave and for which she was paid four-fifths of her daily wage, as required by the Employment Ordinance.

A schematic of Waan’s payslip showing a $6,160 deduction and the sick leave calculation

On 16 June, Hong Kong’s Legislative Council passed a bill amending Hong Kong's Employment Ordinance, protecting workers who experience absences due to compulsory quarantine and isolation orders by counting this time as sick leave, and that employees are entitled to four-fifths of their salary through this period.

But this bill, which had been in discussion since the start of Hong Kong’s fifth pandemic wave in early 2022, is too late to help many workers affected in March and April of this year. Employers are only obligated to count the time for which doctors have issued medical leave certificates as sick leave, and there is no retroactive application of the law.

Before the amendment was enacted, the government relied on employers to self-govern in this matter. In an opinion-editorial, the convenor of Hong Kong’s Executive Council, Bernard Chan, asked “good employers” to show “understanding” to employees. And Law Chi-Kwong, Secretary for Labour, has encouraged employers to be lenient and “kind” to employees.

"It's a fact that workers are sick, and it's a fact that workers are quarantined according to the government's requirements, so why can companies deduct money on the grounds that the law has not been passed?" asked An An, the organising secretary of the Hong Kong Federation of Asian Domestic Workers' Unions (FADWU).

The Thai Migrant Workers Union (TMWU) also believes that, as a government department, the FEHD should take a lead in being a good employer. But at a meeting between the union and the FEHD in early May, the government department insisted that it could only monitor whether companies had violated the law and could do nothing further without the amendment bill being passed.

This meeting was arranged after the TMWU sent an open letter on April 27 to SC Johnson, the FEHD, the Labour Department, the Equal Opportunities Commission, members of the Legislative Council, and others, to discuss the issue of workers losing wages while isolating with Covid-19 according to government pandemic-prevention requirements.

During the meeting with the FEHD, the union suggested the FEHD use a telephone interpreter to make it easier for workers to communicate. The FEHD refused, insisting on Cantonese. An official from the Labour Inspection Division of the Labour Department later met with the district cleaners, in response to the open letter. The representative explained employment regulations to the workers in Cantonese and left a Chinese-English business card with contact numbers, despite the TMWU saying that the workers did not understand Cantonese.

The union later discovered that the staff of the Labour Inspection Division went to the workplace. However, after the visit, the staff still did not know that most of the workers they met that day were of Thai descent. "It seems that there were only two or three (Thai) people," the official stated.

When the TMWU reported to the Labour Department that the workers could not understand, the Labour Department staff argued that the workers who could not read Chinese or English could at least understand the numbers, and they could still call the relevant offices of the Labour Department.

But Waan said that on the day of the inspection, she and the other workers were so nervous and could barely speak, and of course they did not understand the legal terms used by the Labour Department.

Despite having the union’s contact details, the FEHD also continued to contact workers through the company rather than going through the union, with little thought for how the company might pressure workers to stay silent. An An considered this “treating the union as if it didn’t exist.”

SC Johnson ultimately paid back wages to one of the workers, and the FEHD suddenly changed its attitude, taking the initiative to contact the union for the first time, rather than going through the company. However, the staff of the FEHD used Cantonese without an interpreter to ask the Thai worker who received their pay if they were "satisfied." The worker with limited Chinese proficiency did not understand the word "satisfied," so the staff asked, "Are you happy now?" which the worker found to be insensitive.

Although the company would prefer for workers to keep silent, the experience of fighting and winning back pay has inspired others to speak up and assert their rights, with the help of the union.

The next time, the TMWU showed up with a Thai interpreter to a meeting with SC Johnson and offered to withdraw the case from the Labour Department if the company paid the workers’ full wages for their Covid-19 isolation periods in February and March 2022.

As soon as everyone sat down in SC Johnson's office in Kwun Tong, the company representative said, "Everyone should understand one thing: there is no legal requirement now, so this is purely discretionary, compassionate treatment. If a law is passed, the company will follow the law."

The union questioned SC Johnson, who also outsourced cleaners, why some workers were still paid normally during their isolation period, and why the company treats some workers differently. The company representative explained that those who did not have their salaries deducted were outsourced workers from the Government's Leisure and Cultural Services Department (LCSD).

Since most of the venues under the LCSD have ceased their services during the fifth wave of the pandemic, the daily cleaning of the venues has also suspended, so the company did not have to find replacement workers. But the city street cleaning that Waan is engaged in has not been suspended during the pandemic, so to meet the staffing requirements, additional labour was obtained through outsourcing.

In Waan’s case, the company contested the dates of her sick leave by strictly following the time specified in the quarantine order and also checked her attendance records. Waan’s quarantine order was for 21 February to 6 March, but she was physically ill with a doctor’s note through 14 March.

In addition, the company recorded that Waan was absent from work on 23 March, but Waan produced WhatsApp chat records with her supervisor to show that her supervisor told her 23 March was her day off. The union argued that this kind of problem is a failing of the company, and it should never be the workers’ fault that improper records were kept.

Negotiations that day lasted for an hour and a half, and the company agreed to issue Waan’s sick leave allowance during the isolation period and add back the wrongly deducted salary on 23 March. On 7 June, Waan received a check for more than $4,000.

But for non-local cleaners, and the larger group of outsourced cleaners, the process of safeguarding their rights is far from over. Two colleagues at Waan's cleaning job on her first shift were also absent for several days because of the Covid-19 infections. They did not have community centre test results, quarantine orders, or any supporting documents as a result of barriers and disincentives for seeking and receiving diagnosis and treatment. It was particularly difficult to obtain sick leave allowances. The Employment (Amendment) Bill 2022, which has just passed, still cannot help them recover their salaries.

An An is still very angry with the FEHD and the Labour Department. "They don't care about vulnerable groups at all, thinking that everyone is like them. They can speak Chinese and English and can register online. They ‘walk so fast they’re flying’ and don't worry about food, clothing, housing, and transit." An An concluded, "I’m not done with them.”

*Waan requested to use a pseudonym for her privacy.

All dollar amounts in this article refer to Hong Kong dollars.