After several major telecoms companies were blacklisted by the outgoing Trump administration, China committed US$1.4 trillion to its homegrown chip industry over a five-year period.

While the money flowing into the industry has increased, workers aren’t sharing in that bounty. The pristine environment of semiconductor fabrication plants (commonly referred to as “fabs”) hides an uglier reality of grueling working conditions and low pay.

The China Industrial Economic Statistical Yearbook states that the number of workers in electronic equipment industries grew by more than two million over the past ten years, with 8.8 million workers now in the industry. CLB interviewed a fab worker this month who described an environment where employees are under extreme pressure and where chips are more important than people.

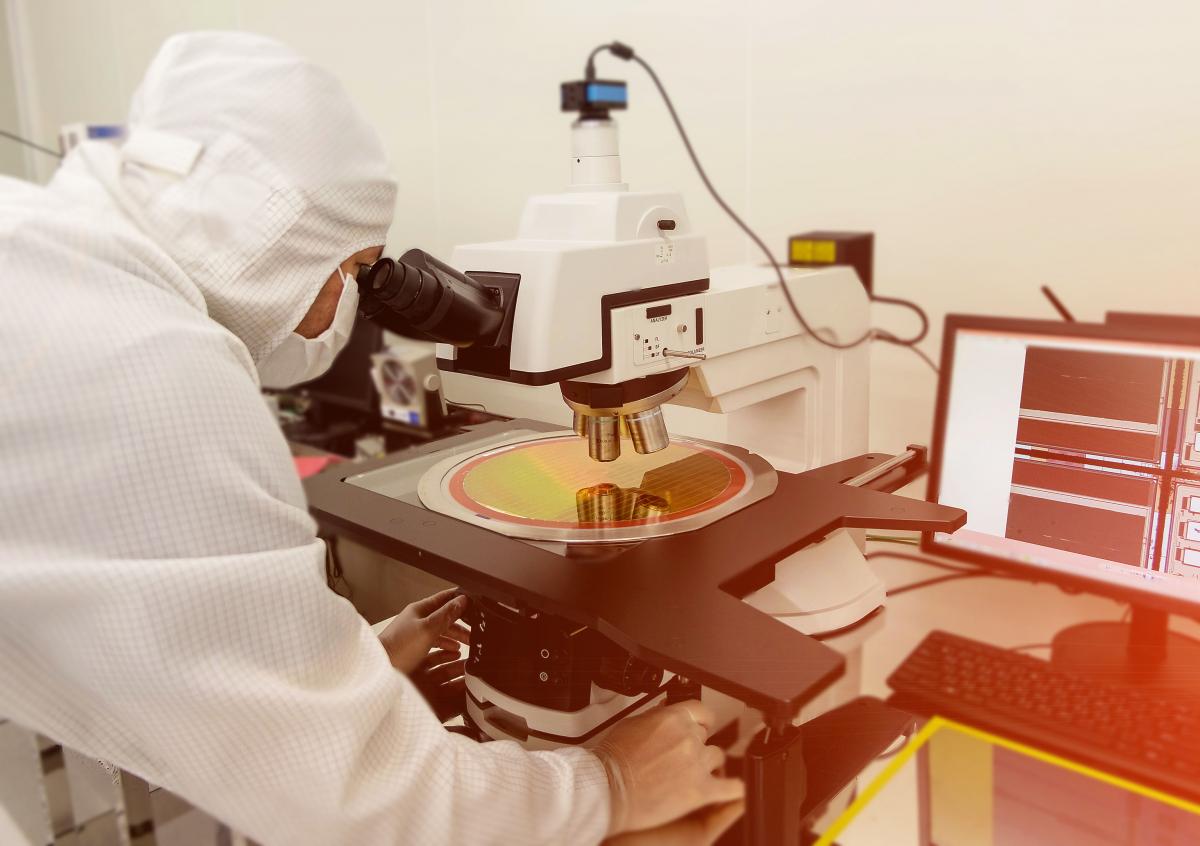

Photograph: MS Mikel/Shutterstock

The process of creating an integrated circuit is onerous. It requires extracting silicon from sand, converting it to polysilicon, slicing it into silicon wafers, followed by photolithography, packaging and cutting. Workers who make chips keep punishing schedules, working 12 hours a day in isolation. Day shift workers clock in at 7:45 am and take their first break at 11 am. After an hour for lunch, they work from 12 pm to 8 pm.

The fab employee CLB interviewed, who asked not to be identified, worked in processing polysilicon wafers, which involves checking input values and transporting the products to the relevant machines for processing and quality checks. “The machine spins all day and workers must guarantee that chips have no defects and that the machine does not stop even for a moment.”

The worker told CLB that workers had previously put fewer wafers into lithography machines to make their jobs easier. However, their managers accused them of insufficient output and demanded they increase their efficiency. The output of lithography machines was increased from 1,000 pieces per shift to 1,300, an increase in labour productivity of one third. The worker expected factory managers to further increase output in the future.

Employers are preoccupied with productivity, but they don’t pay fair wages. Fab workers have to undergo six months to one year of training and pass exams before they can operate machines, but day shift workers report salaries of only 3,000 yuan per month. Similarly skilled workers in other types of factories can earn more than 6,000 yuan per month.

Workers often leave feeling they have gained little in terms of specialist knowledge. “I originally thought that working in a wafer processing plant I would learn a craft, but that was not the case. In this factory, there is no room for improvement, and the salary is low,” the worker told CLB.

Unsurprisingly, fabs see high employee turnover rates. “There’s a lot of rest hours, but workers don’t want to be here,” the worker told CLB, reciting a common saying among fab workers: “Three are recruited, and three leave.”

New workers are held to rigid standards and are fined for any mistakes. CLB’s interviewee told us that one of their colleagues was dismissed after knocking down a cart. Cracks and particles were detected in the wafers, causing damage estimated at 660,000 yuan.

The high turnover and the isolated nature of fab work makes organising difficult. Workers are encased in “cleanroom suits,” unable to use their phones during working hours. They find it difficult to maintain relationships with their relatives and friends, let alone build alliances with other workers. If working conditions are to improve in this developing industry, trade unions must take concerted action, but so far, they remain silent.