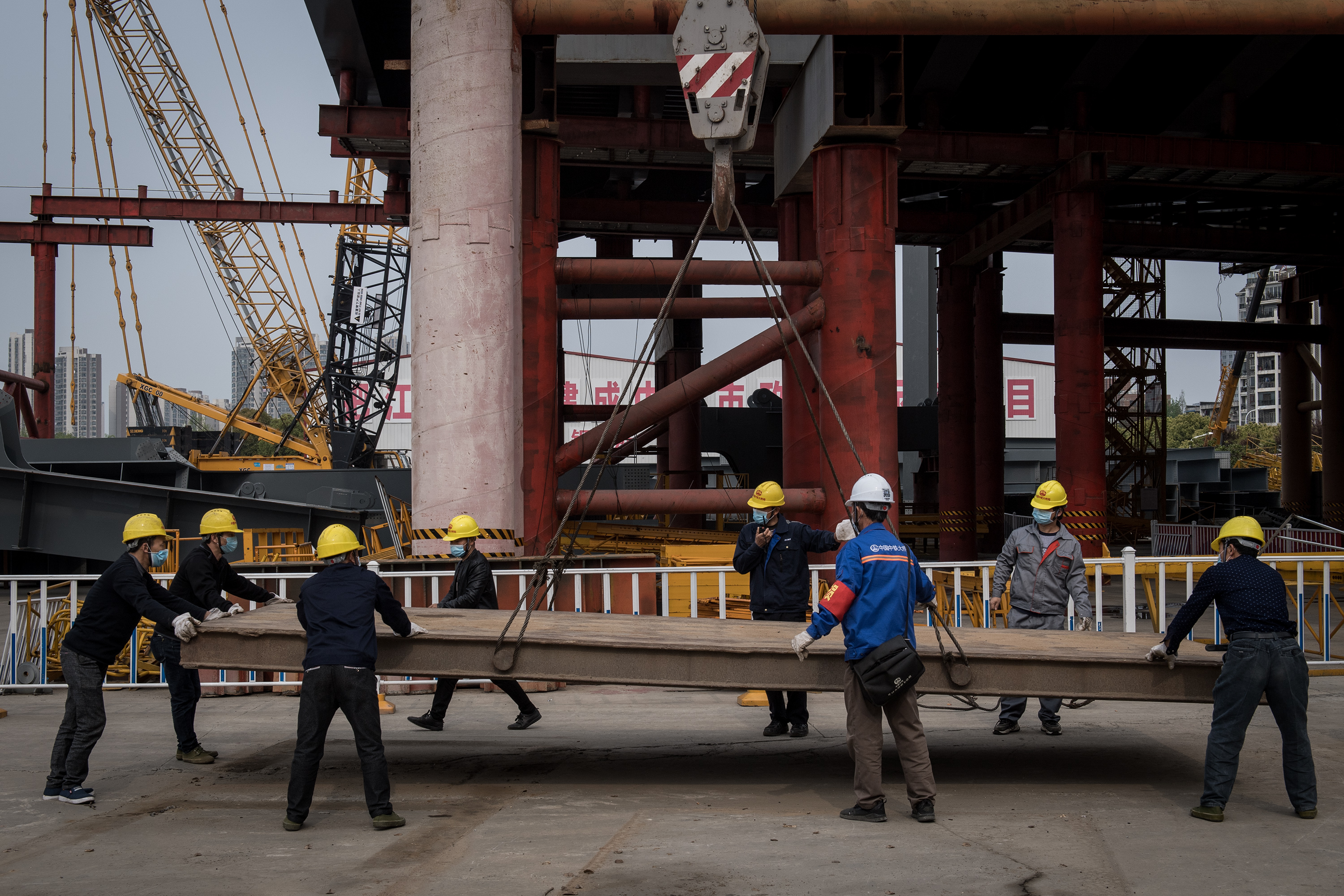

China has seen a spate of tower crane accidents at construction sites over the last two weeks, as work on building and infrastructure projects resumes after the Covid-19 pandemic shutdown.

China Labour Bulletin’s Work Accident Map recorded at least eight accidents in the 11 days between 14 May and 24 May in Hunan, Anhui, Sichuan, Yunnan, Shandong, Zhejiang and the far western region of Xinjiang. It appears that there were several fatalities as a result of these accidents, but the exact injury and death toll is unclear.

The most serious accident occurred on 22 May in the coastal city of Weifang in Shandong. One tower crane at a large-scale construction project suddenly collapsed and crashed into another crane nearby. At least one worker died and another injured in the incident. Another worker died four days earlier when a tower crane at a construction site in the Xuancheng Economic and Technological Development Zone in Anhui collapsed. The damage was so extensive that construction work at the entire site had to be suspended.

In the other incidents, workers were able to escape with their lives. During a crane collapse at a construction site in Changsha, for example, the crane operator managed to climb to safety when his cab lodged up against the side of the building under construction.

Tower crane accidents in China are routinely blamed on operator error or cranes lifting building materials in excess of the crane’s load capacity. However, there is a more fundamental, systemic problem in the construction industry that has undeniably contributed to the recent flood of accidents.

In the 2000s, crane operators were generally skilled workers attached to state-owned construction companies who worked in regular shifts. During the infrastructure boom that followed the 2008 global economic crisis, however, there was an explosion in the number of private crane leasing companies that often hired rural migrant workers without proper training as crane operators. Today, many crane leasing companies do not even hire operators directly but outsource recruitment to labour contractors, etc.

Problems have been compounded by the retirement of older, experienced crane operators and an influx of younger, inexperienced operators who only receive a minimal salary and therefore have to work excessively long hours just to earn a decent wage. It is quite common for a crane to be operated by a single worker all day—rather than by several workers taking short shifts—leading to a higher risk of accidents through fatigue.

The low pay and hazardous working conditions were highlighted two years ago by the dozens of strikes and protests organized by tower crane operators around Labour Day 2018. CLB’s Strike Map recorded protests in Sichuan, Gansu, Henan, Fujian, Hunan, Jiangsu, Guizhou, Jiangxi, Hubei and Guangxi in the week prior to the holiday, and even the state-backed Global Times reported that “crane operators protested across China during Labour Day demanding better pay and an eight-hour working day.”

There are very clear and detailed government regulations related to the safe operation of tower cranes and all operators are supposed to hold a government-issued special operation certificate before they can be employed.

In reality, enforcement of these standards has been very lax and little has been done to safeguard the interests of crane operators. In fact, increased competition among crane leasing companies has led to further cost cutting and a lack of essential maintenance, resulting in structural cracks in the cranes, loose bolts and joint failures.

Given the failure of the local authorities to properly supervise the tower crane companies, there is clearly a need for the official trade union to step into the breach and play a far more active role in the construction industry as proposed by CLB in our most recent research report, Holding China’s trade unions to account: An in-depth investigation into the All-China Federation of Trade Union’s reform initiative.