China’s urban unemployment rate increased by 0.1 percent in April to stand at 6.0 percent, the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) announced today. It was the third month in a row that the rate has stayed around six percent after jumping sharply in February.

The official figure for unemployment among workers aged 16 to 24, however, was more than twice as high, standing at 13.8 percent, a 0.5 percent increase compared with March.

China’s more than eight million college graduates will have a particularly difficult time finding decent employment this year despite government schemes specifically aimed at boosting graduate employment. The problem has always been the huge mismatch in the employment expectations of graduates and economic reality. Now, with the economic slowdown and the Covid-19 pandemic, graduates are being forced to adjust their expectations.

Zhao Xingxing, a 24-year-old graduate from Henan, told the South China Morning Post this week, “I realised I was too optimistic. I thought I was really good. I realise I’m just an average college student.” Zhao said she has cut her expected monthly salary from 4,000 yuan to 3,000 yuan, about the same wage level as for migrant workers in the catering industry.

The NBS also reported that only 3.54 million jobs were created in the first four months of the year, 1.05 million less than in the same period last year. Moreover, many of the new jobs created now tend to be part-time positions, day labourers and jobs in the gig economy that offer no safeguards of continued employment or social insurance.

The official unemployment rate is based on surveys in major cities and as such, does not reflect the employment situation in smaller urban and rural areas. However, the NBS did report an unemployment rate of 5.8 percent for the 31 largest cities in China, indicating at higher rate for smaller cities.

It is clear from media reports and the volume of individual complaints on social media about the perilous employment situation in China that dissatisfaction with the government’s handling of the crisis is growing.

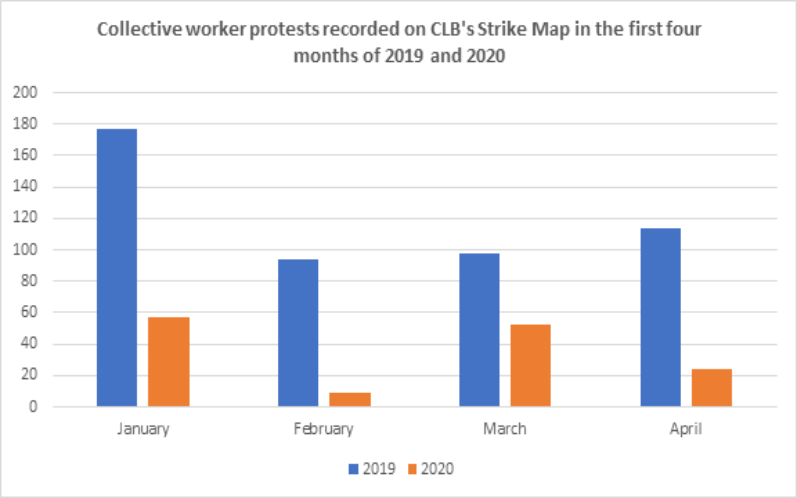

Thus far however, that dissatisfaction has not led to an obvious increase in collective worker protests in China. In fact, the number of protests recorded on China Labour Bulletin’s Strike Map in the first four months of 2020 is only 142, compared with 483 in the same period last year (see graph below).

Given the continued threat of Covid-19 infection, it is not surprising that workers are still reluctant to stage large-scale protests or gatherings. Moreover, many workers might consider mass protests to be a lost cause or even counter-productive in the current economic environment.

Most of the collective protests that we have seen since the Lunar New Year have been in the service and transport sectors, with taxi drivers being particularly active because of the continued financial burden of vehicle rental fees that they have to endure.

There have been relatively few protests in the manufacturing sector. Workers are not necessarily being laid off en masse, rather employers have placed staff on unpaid leave or only paid their basic wage because there is no overtime available. The basic wage for production line workers in China has never been a living wage so with no overtime, workers often have no choice but to leave the factory and seek work elsewhere.

In the past, younger workers laid-off from factories could often find employment in the expanding services sector. However, services contracted for the third month in a row in April, with the Caixin Services PMI standing at 44.4 last month, up slightly from 43 in March, and a record low of 26.5 in February. A number above 50 indicates an expansion in activity, while a figure below points to a contraction.

One of the reasons for the contraction in services is that many retail and catering businesses in manufacturing hubs were dependant on factory workers for custom, and with the factory workers no longer present or unable to afford these services, business has declined dramatically.

Many small and medium-sized enterprises in tourism, leisure, catering and hospitality have been particularly hard hit by the pandemic and can no longer afford to retain let alone hire new staff.