Last month, a China Minsheng Bank (CMBC) manager was reportedly fired when his six month sexual harassment of a female subordinate was revealed by the victim online, reports the Beijing Youth Daily.

The manager, a Beijing-based deputy department head surnamed Guan, invited his co-worker, Wang Qi (pseudonym) to a hotel room, threatening to fire her if she refused to comply. For six months, Wang refused his repeated advances. Undeterred, Guan began threatening Wang, announcing that the bank would soon be determining which workers to layoff.

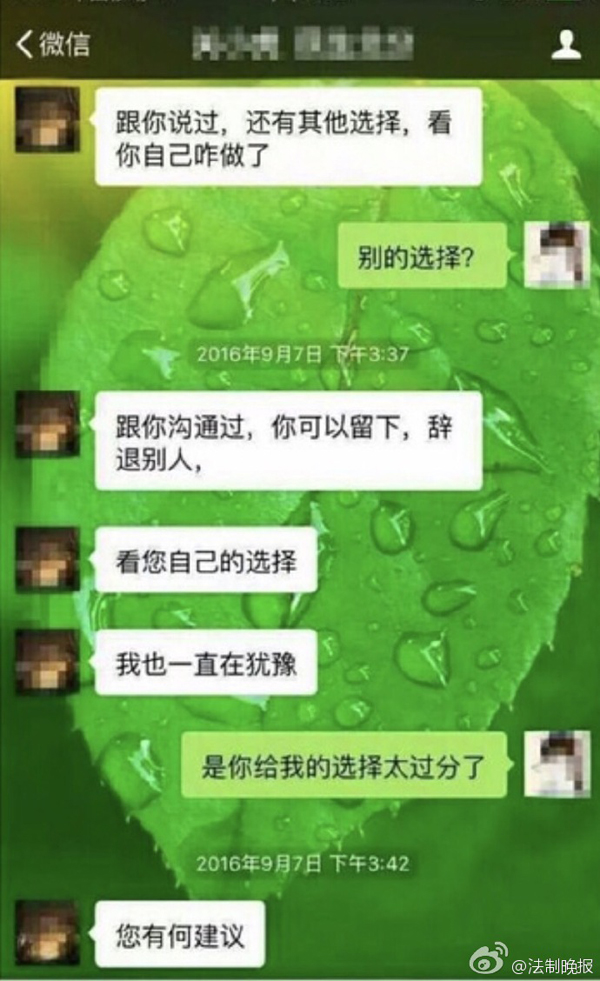

It doesn't need to be this way: "There are other options, it depends on what you decide to do."

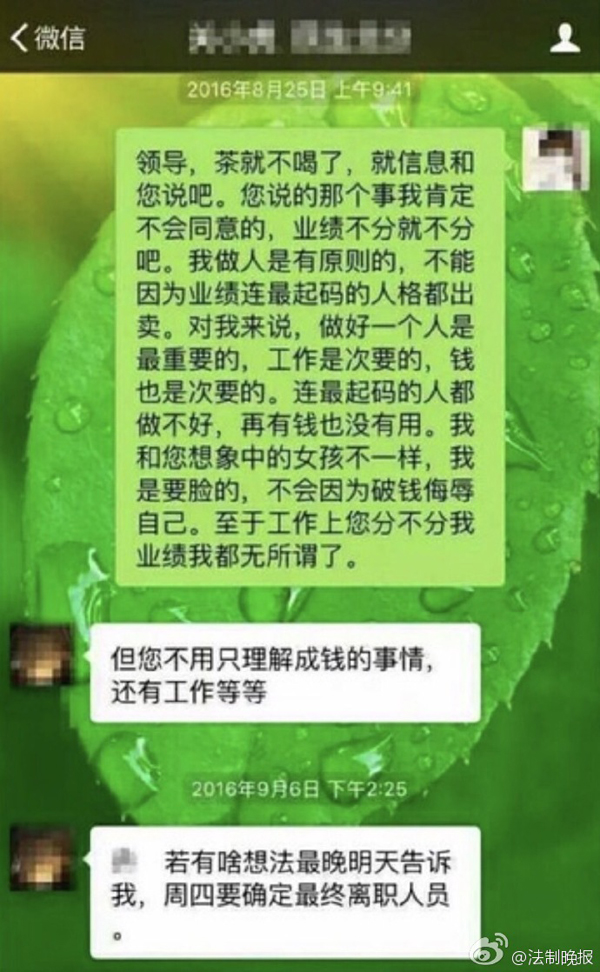

“There are other options” said Guan, “...it depends on what you decide to do.” Wang’s decision was damning – in December, she quit her job and posted screenshots of the incriminating messages in a 60-member internal WeChat group.

When the posts were made public, netizens nationwide expressed outrage. Faced with mounting pressure, the initially-reluctant Beijing branch had no choice but to announce in mid-December that it had fired the male manager and asked him to make an apology. The bank said it had also reached out to Wang offering support.

Thanks, but no thanks: "To me, dignity comes first, then job security, money is also secondary. When dignity is lost, money is of no use."

If nothing else, the bank’s response demonstrates a key feature of workplace sexual harassment and violence in China: the systemic failure on the part of employers to provide necessary labor protections for employees. Still without a job, Wang is set to receive no material compensation from the bank, and, after the media storm subsides, the unnamed male assailant will likely walk away scot-free – no investigation, no material damages, no public record of the incident, and no real legal accountability. With the costs of openly opposing sexual harassment so high, many victims feel rightly isolated and helpless about their circumstances.

Sadly, the case is far from unique in China. Every couple of years, Chinese social media networks drum up a widely publicized example of workplace sexual harassment. In the absence of stronger laws that force employers to comply with legal protections and protect victims from retaliation, employers like Minsheng Bank are free to cook up tepid public apologies while otherwise leaving workers empty handed and assailants off the hook.

Underreported and under-prosecuted

Everyday 330 million Chinese women go to work, and, according to a 2009 report from two professors at City University in Hong Kong, 80 percent of working Chinese women report experiencing sexual harassment at some point in their working lives. Sexual harassment and gender-based violence in the workplace, especially in low-wage or poorly regulated industries—such as retail and domestic work—continue to slip under the radar, underreported and under-prosecuted.

Widespread as harassment may be, in China, legal action against assailants and their employers remains few and far between. China’s Law on the Protection of Women’s Rights and Interests, passed in 2015, promises explicit protections for women from sexual violence and even enabled women to take perpetrators to court, potentially subjecting employers to fines and lawsuits for mishandling cases.

But the hard truth is that courtrooms almost always fall short of delivering justice — from lenient and often non-existent punishments for perpetrators to an extremely high burden of proof for victims, plaintiffs face a swathe of challenges from China’s legal system. According to Zhang Jiangzhou, a judge with Beijing Haidian District People's Court, since 2005 around 10 women have sued alleged sexual assaulters in court, but only one won her case. This is partly because what constitutes sexual harassment in China is not clearly defined. In this context, very few employees have prevailed in getting their employers to pay up— and when they do, they often receive only minimal damages.

Uphill courtroom battles are not the only challenge victims face. Noncompliant human resources departments and union representatives routinely shut victims out. Peng Jin, a lawyer specializing in civil affairs litigation at Yi Fa Law Firm in Beijing, told China Daily that the appropriate organizations to report sexual harassment complaints to are workers' union at a workplace and internal departments within the company.

"All workers' rights are protected under the Criminal Law and the Labor Law. However, not all assault activities at workplaces are punishable under legal provisions," she acknowledges. "Therefore, related regulations should be written into employee handbooks to provide means for workers to file complaints. Meanwhile, departments for overseeing workplace harassment should be setup to implement the regulations."

Yet in Wang’s case, colleagues revealed that when Wang tried to inform the bank’s human resources department, she was told there was “no evidence” to her claims, dismissing the charges as “not substantive” because of the “behavior was limited to WeChat.” The bank also allegedly pointed to Wang’s status as a contract worker, and not a full employee, as grounds for inaction regarding her case.

It’s clear that for Wang, and for victims across China, the one-sided laws and retaliatory employer practices have failed to adequately protect workers from sexual violence. Her case points to a major feature of workplace sexual harassment, and one of the leading reasons few cases are ever formally reported to higher-ups: for victims, speaking up often only leads to trouble in the form of forced resignations, dismissal, physical danger, and retaliatory harassment that have real and material consequences for workers in China. Without structural changes in workplace protections and stronger penalties for employers and assailants who break the law, the door is left wide open for employers to shirk their legal responsibilities and act with impunity.