China’s Social Insurance Law (社会保险法), which went into effect five years ago on 1 July 2011, was supposed to create a comprehensive social insurance system in which the responsibilities of employees, employers and the government were clearly spelled out.

However, the majority of employers simply ignored their legal obligations to provide employees with a basic pension, unemployment, medical, work-related injury and maternity insurance. Local government officials, likewise, ignored their obligation to enforce the law, leaving hundreds of millions of workers without an effective social welfare safety net.

Now, there is growing evidence that China’s increasingly pro-business government is looking to place the burden of social security firmly on to the shoulders of workers and individual citizens and gradually reduce the limited burden currently carried by employers.

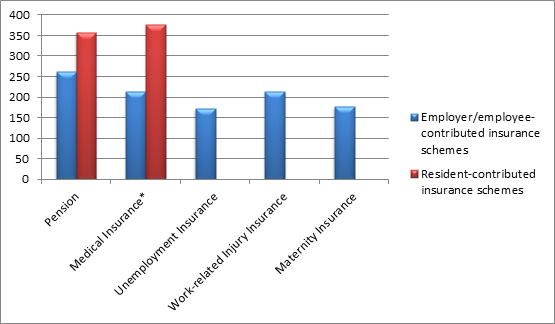

The government’s own figures (2015年度人力资源和社会保障事业发展统计公报) show that in 2015, only 262 million workers, about one third of China’s total workforce of around 775 million, actually had a basic pension, while only 213 million workers had basic medical insurance provided by their employer.

By contrast, there are currently 357 million working age people with a government-backed pension that does not require employer contributions. The urban and rural resident basic pension (城乡居民基本养老保险), created by the merger of rural and urban resident pension schemes in 2014, relies solely on individual contributions from residents backed by limited government subsidies. So while a lot more people may appear to be covered, the absence of employer contributions means that the benefits accrued are token at best. Indeed, official figures show that the average pay-out for the 148 million people receiving pension benefits from the urban and rural resident scheme in 2015 was just 1,432 yuan for the whole year. The average annual pay-out to the 91 million retirees with a basic urban pension contributed to by their employer, on the other hand, was about 20 times higher, standing at 28,363 yuan in 2015.

Responsibility for medical insurance likewise is gradually shifting away from employers towards individual citizens. In 2010, for example, 178 million workers had basic medical insurance from their employer, while 195 million people were covered by the urban resident medical insurance scheme. Five years later in 2015, the number of workers covered by their employer had risen by about 20 percent to 213 million. In the same period however, the number of people covered by the urban resident medical insurance scheme had nearly doubled to reach 377 million.

Unemployment, work-related injury and maternity insurance for employees are obviously tied to the workplace and, as of yet, there are no alternative urban resident-based schemes. There is a proposal to eventually merge maternity insurance with the basic medical insurance scheme but no detailed plans have been published yet.

Social insurance coverage for employees and working age residents in 2015 (millions)

* The figure for resident medical insurance scheme includes those over the retirement age

In addition to emphasizing resident insurance schemes at the expense of employee/employer schemes, the government is gradually chipping away at the insurance contributions employers have to make under existing laws and regulations. A notice jointly issued on 14 April this year by the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security and the Ministry of Finance (人力资源社会保障部 财政部关于阶段性降低社会保险费率的通知) stressed the need to gradually reduce social insurance contribution rates across the board, with the greatest reductions reserved for the employer. The Notice states explicitly that the measures are aimed at “reducing costs for enterprises and enhancing their vitality.” Several provinces and cities, including Beijing, have already started to reduce employer pension contributions by one percent from 20 percent to 19 percent. This follows a similar one percent reduction in contributions to unemployment insurance earlier in the year.

CLB’s newly revised and updated introduction to China’s social security system argues that the Chinese government should not reform the system just to make life easier for employers; social insurance is too important for such short-sighted measures. Instead, the government needs to find a way to accommodate the competing interests of labour and capital in creating a realistic and stable social security system; one that looks after workers during poor health and old age but also helps to create a content and well-paid workforce that in turn can help develop the domestic economy through greater innovation, productivity and consumption of goods and services.