Wu Guijun, a 40-year-old migrant worker and father of two, has been detained for nearly five months and faces possible criminal prosecution after staging protests against his employer and petitioning the local government in Shenzhen.

Wu was one of 300 workers at Diweixin, a Hong Kong-owned furniture maker, who took to the streets of Shenzhen on 23 May 2013 in protest at the company’s refusal to discuss worker compensation for a planned closure of the factory and relocation to a cheaper location in neighbouring Huizhou.

The workers were demanding that the Shenzhen municipal government intervene after a three-week-long strike and fruitless negotiations with management. Neither the local trade union nor the district labour department had provided any substantial help in the negotiations.

More than 200 workers were detained by the police during the 23 May protest. Of those, 20 were held for 13 days and two for 37 days. Wu Guijun, who was one of seven elected workers’ representatives at Diweixin, has now been detained for 148 days.

Last month, on 11 September, 36 of Wu’s co-workers signed open letter to the Shenzhen Federation of Trade Unions, asking it to fulfil its obligations to protect workers’ rights and exert pressure on the local government to release Wu.

A week later on 18 September, the well-known labour rights academic, Wang Jiangsong, posted a Weibo about Wu’s detention.

Tomorrow is the Mid-Autumn Festival; it is also 121 days since Wu Guijun has been denied his freedom! As an elected worker representative, Wu was arrested on 23 May, and he is still under detention. The police have neither informed Wu’s family of the crime he is supposed to have committed, nor have they issued any formal detention notice. Such brutal deprivation of people’s freedom absolutely violates the law.

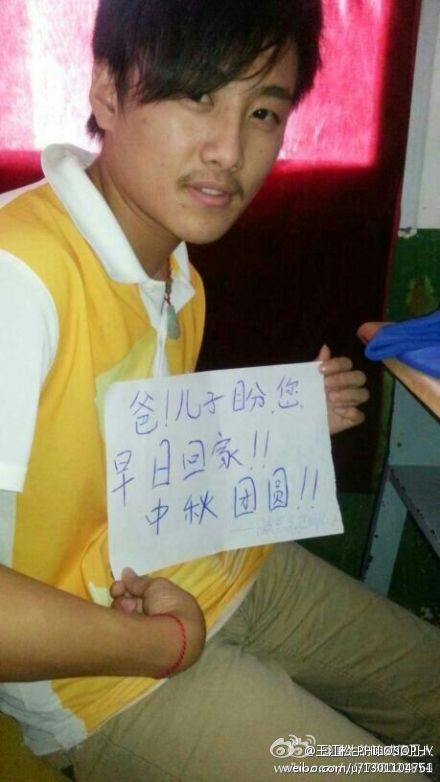

Wang also enclosed the 11 September letter by Wu’s co-workers, a letter from Wu’s wife to the Shenzhen municipal government, and a photo (below) of his teenage son holding a sign that read “Dad, come home soon, so that we can be together for the Mid-Autumn Festival!”

This post got re-tweeted more than 12,000 times and caught the attention of the international labour community, which is now offering its support.

This post got re-tweeted more than 12,000 times and caught the attention of the international labour community, which is now offering its support.

At the end of September, several labour and human rights organizations co-signed a letter to the Mayor of Shenzhen and the president of Shenzhen’s Federation of Trade Unions, asking the government and union to defend the right to strike and to release Wu from detention. And on 1 October, the Hong Kong Confederation of Trade Unions held a rally at the Central Government Liaison Office in Hong Kong, also demanding Wu’s release.

Two weeks later, Wu’s case was reported in the official Guangzhou newspaper, the Yangcheng Evening News, and quoted Professor Wan Xiangdong of Sun Yet-san University as saying that the government and trade union tend to prioritize the maintenance of social stability and the reduction of economic losses in labour disputes and this puts the workers at a distinct disadvantage. Wan noted that this imbalance in power made collective bargaining difficult because workers and management were not on an equal footing.

Wu’s lawyer, Pang Kun, had two days earlier, on 13 October, submitted an open letter to the Procuratorate of Shenzhen’s Bao’an District asking them to drop the prosecution against Wu based on a lack of evidence. Wu reportedly faces the criminal charge of “gathering a crowd and disturbing the order of public transportation.”

Wu’s co-workers also registered a dedicated Weibo account, the Steadfast Workers of Diweixin, to support Wu and started gathering online signatures for their second open letter to the Shenzhen Federation of Trade Unions.

Although Wu’s detention has got the most publicity, there have been dozens of worker protests over the last few months that have also resulted in workers being beaten or detained by local police. This indicates that many local authorities are still struggling to deal with labour unrest in their districts and all too often resort to negative tactics in their desire to maintain social order.