There has been a noticeable decline in the number of strikes and protests by coal miners since April this year as local governments, nervous about China’s economic slowdown and social instability, delay plans to cut production and lay-off around one million workers.

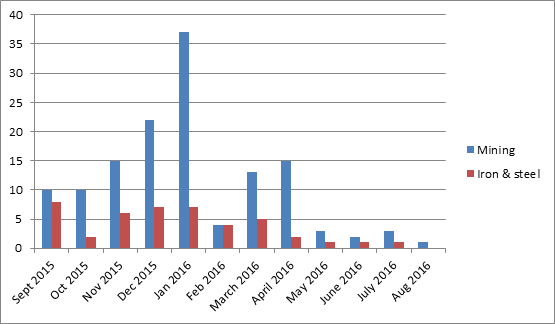

A similar pattern of declining protests can be seen in the iron and steel industry as central government demands to reduce overcapacity and lay-off excess staff have been meet with continued resistance from local officials (see chart below).

Protests by miners and iron and steel workers in China: September 2015 – August 2016

China announced plans in February to lay off 1.8 million workers in the coal and iron and steel industries, or about 15 percent of the workforce. But by the end of July this year, provincial governments had only met 38 percent of their targets to cut production capacity in coal mining and 47 percent of their targets in the steel industry, according to Zhao Chenxin, spokesperson for the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), quoted by Caixin on August 16. The south-western province of Yunnan hadn't even reached 10 percent of its target for trimming coal capacity, Zhao said.

The turning point for government officials may have been the massive and highly publicised protest by thousands of coal miners in the north-eastern city Shuangyashan, which coincided with China’s National People’s Congress in March, and made very apparent the dangers of failing to pay workers on time and laying off workers without proper compensation.

Another factor is that commodity prices have started to rebound this year making some mines and iron and steel plants that were slated for closure more economically viable. Local government clearly don’t want to cut capacity only to find that officials in the neighbouring province have not followed suit and are now better placed to take advantage of higher prices.

It is also important to note that China’s coal industry, in particular, has been in decline for around three years, during which time mass protests by miners over lay-offs and wage arrears have become increasingly commonplace, reaching a peak of 37 strikes and protests in January 2016, just prior to the Chinese New Year.

It is possible that the most intense phase of unrest in the coal industry is already over but if higher prices fail to improve conditions for the remaining workforce, there will almost certainly be renewed protests over wage arrears etc. in the run up to next year’s Chinese New Year.