What rights do China’s workers have under the law?

China has a comprehensive legal framework that gives workers a range of entitlements and protects them from exploitation by their employer. Workers have the right to be paid in full and on time, a formal employment contract, a 40-hour working week with fixed overtime rates, social insurance covering pensions, healthcare, unemployment, work injuries and maternity leave, severance pay in the event of contract termination, equal pay for equal work, and protection against workplace discrimination. Workers also have the right to form an enterprise trade union (see below for more details), and the enterprise union committee has to be consulted by management before any major changes to workers’ pay and conditions. Since China’s economic slowdown in the mid-2010s, however, there has been little new legislation to bolster workers’ rights and senior government officials have openly discussed rolling back some existing protections in a bid to create a more pro-business legal environment. The most important laws governing labour relations in China are the 1995 Labour Law 中华人民共和国劳动法, 1992 Trade Union Law (amended 2001) 中华人民共和国工会法(2001 修正), 2008 Labour Contract Law (amended 2013) 中华人民共和国劳动合同法(2013), and the 2008 Labour Dispute Mediation and Arbitration Law 中华人民共和国劳动争议调解仲裁法.

A more comprehensive list of laws and regulations on labour relations is available here.

How is the law enforced?

Local governments in China are responsible for enforcing labour law and ensuring that workers’ rights are protected. However, the local labour authorities are generally under-funded and under-staffed and lack the ability and the will to enforce the law. Local governments have generally been more concerned with boosting the local economy and creating a business-friendly environment than with protecting workers’ rights. During the reform era in China, it could be argued that the government gradually abdicated its power in labour relations to business owners, giving employers the ability to dictate the pay and working conditions of their employees. As such, it has largely been up to the workers themselves to ensure that labour law is enforced by taking collective action to demand that wages and overtime are paid in full, proper contracts are signed, social insurance contributions are paid in full and that compensation is paid in the event of injury or contract termination. It could be argued that enforcement of the law has weakened over the last decade as the economy has slowed and governments sought to protect local investments. Following the implementation of the Labour Contract Law in 2008, there was an initial push by local governments and the trade union to ensure that China’s most vulnerable workers, rural migrants, did sign formal employment contracts as prescribed by the law. However, the initiative never gained momentum. A National Bureau of Statistics survey of migrant workers in 2009 showed that 42.8 percent of migrant workers had signed a contract with their employer but, in 2016, that proportion had dropped to just 35.1 percent.

Food delivery workers on strike in Chongqing, 16 May 2018. Photo: Chongqing Evening News Slow News

Do workers in China have the right to strike?

The right to strike was removed from the Constitution in 1982 as part of the “modernizing” reforms of then leader Deng Xiaoping. However, there is no legal prohibition on workers taking strike action. In fact, as noted above, workers often have no option but to go on strike if they are to get their employer to listen to their demands. China Labour Bulletin’s Strike Map, which has recorded more than 10,000 incidents since 2011, shows that strikes and other forms of collective protests are commonplace across the whole of China and in all sectors of industry. Strikes are usually small-scale and short lived although there have been some major events in recent years such as in April 2014 when around 40,000 workers at the Yue Yuen shoe factory complex in Dongguan went out on strike for two weeks. Strikes have also been organized simultaneously in different cities across China, such as those by tower crane operators and truck drivers in May and June 2018 respectively. Occasionally, workers will be arrested after taking part in or organizing strikes but if they are charged at all, it will be with public order offences such as “gathering a crowd to disturb social order” rather than with taking part in a strike per se. A more common form of retribution is for strike leaders to be sacked by management either during the strike or a few months afterwards, in a process known in China as “settling scores after the harvest is gathered” (秋后算帐).

Do workers in China have freedom of association?

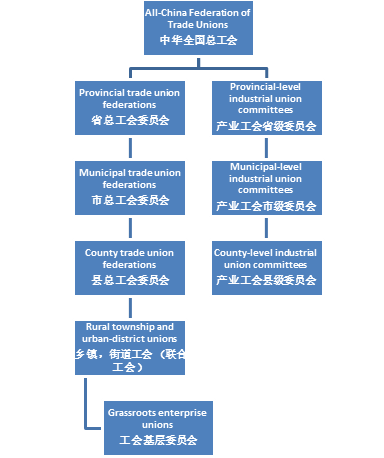

No. There is only one legally-mandated trade union, namely the All-China Federation of Trade Unions (ACFTU). All enterprise trade unions have to be affiliated to the ACFTU via a hierarchical network of local and regional union federations. (See simplified organizational chart right). The ACFTU is primarily under the control and direction of the Chinese Communist Party. Any attempt to establish an independent trade union movement is seen by the Party as political threat. The only time in the history of the People’s Republic of China that an independent union was established was the short-lived Beijing Workers’ Autonomous Federation in 1989. The BWAF was declared an illegal organization and disbanded in the wake of the military crackdown in Beijing on 4 June 1989.

No. There is only one legally-mandated trade union, namely the All-China Federation of Trade Unions (ACFTU). All enterprise trade unions have to be affiliated to the ACFTU via a hierarchical network of local and regional union federations. (See simplified organizational chart right). The ACFTU is primarily under the control and direction of the Chinese Communist Party. Any attempt to establish an independent trade union movement is seen by the Party as political threat. The only time in the history of the People’s Republic of China that an independent union was established was the short-lived Beijing Workers’ Autonomous Federation in 1989. The BWAF was declared an illegal organization and disbanded in the wake of the military crackdown in Beijing on 4 June 1989.

What is the main role of China’s official trade union, the ACFTU?

The ACFTU is the world’s largest trade union, with around 303 million members, including 140 million migrant workers, in 2.81 million grassroots trade unions in 2018, according to official figures. This translates into a unionisation rate of 37 percent, higher than in most developed nations with the exception of those in northern Europe. In reality, however, the vast majority of Chinese union members either do not know that they are union members or have little faith in the ability of the union to represent their interests. The Trade Union Law stipulates that enterprises in which a trade union has been established must contribute two percent of monthly payroll to union funds. Worker contributions are negligible. As a result, the majority of enterprise trade unions in China are essentially controlled by management and represent the interests of management. Only very occasionally will enterprise trade union leaders support workers in a dispute against management, as was the case of Huang Xingguo who in 2014 led Walmart employees in a month-long campaign for lay-off compensation after the closure of their store in the central city of Changde. There are reportedly more than one million full-time trade union officials employed in various federation offices across China. They are essentially government bureaucrats with little understanding of the needs of workers or how to represent them in negotiations with management. The ACFTU traditionally sees itself primarily as bridge or mediator between workers and management rather than as a voice of the workers. However, the ACFTU is under pressure to change. Pressure is being applied by workers and worker activists who are demanding that the union actually stand up for their interests and their interests alone. Pressure is also coming from the highest echelons of the Chinese Communist Party in Beijing who need the ACFTU to play a more active role in ensuring that ordinary workers can earn a decent wage and that the gap between rich and poor, which has expanded exponentially during the reform era, can begin to narrow.

What is the role of civil society in supporting the workers’ movement?

In the 2000s and early 2010s, there were dozens of Chinese labour groups, concentrated mainly in the southern province of Guangdong, which actively supported workers in their demands for better pay and working conditions. These organizations essentially did the work of a real trade union, helping workers involved in a collective dispute with their employer to formulate their demands, elect bargaining representatives, develop a bargaining strategy and maintain solidarity among the workforce. They also helped workers to utilize the increasingly powerful tools provided by social media to put pressure on local trade union officials to support workers’ legitimate demands. In 2015 however, the authorities launched a massive crackdown on civil society that led to the closure of many influential labour organizations. Although depleted, civil society still exists in China as an informal network of individual activists who can provide concrete help and guidance to workers and ensure the workers’ movement stays on track as well as keeping the ACFTU accountable to its members.

Worker representatives with civil society activist Zhang Zhiru during a bargaining session with management at Hietech Precision Industry Co. in Shenzhen: May 2016

Is there collective bargaining in China?

Collective bargaining in China is still at an embryonic stage. There is no formal mechanism for collective bargaining at the national level and since the trade union is currently unable to effectively represent the workers in bargaining, workers have been forced to take matters into their own hands. Collective bargaining usually only occurs after workers have gone out on strike. Workers, particularly factory workers in Guangdong, are often willing to elect their own bargaining representatives and put sustained pressure on management to come to the negotiating table. In many cases, management will agree to make some concessions to workers’ demands, usually just enough to get them to call off their strike action. Once the dispute has been resolved however, there is rarely any follow up action and much of the solidarity generated by the strike tends to dissipate. One of the few local regulations that provides a legal framework for collective bargaining is the Guangdong Provincial Regulations on Enterprise Collective Contracts (广东省企业集体合同条例), which went through numerous drafts before a highly watered-down version was finally approved in September 2014. The regulations, as promulgated, failed to give workers a real opportunity to get involved in the bargaining process. As a result, they have been largely ignored and genuine collective bargaining in the province remains arbitrary and haphazard at best.

What is the role of the courts in resolving labour disputes?

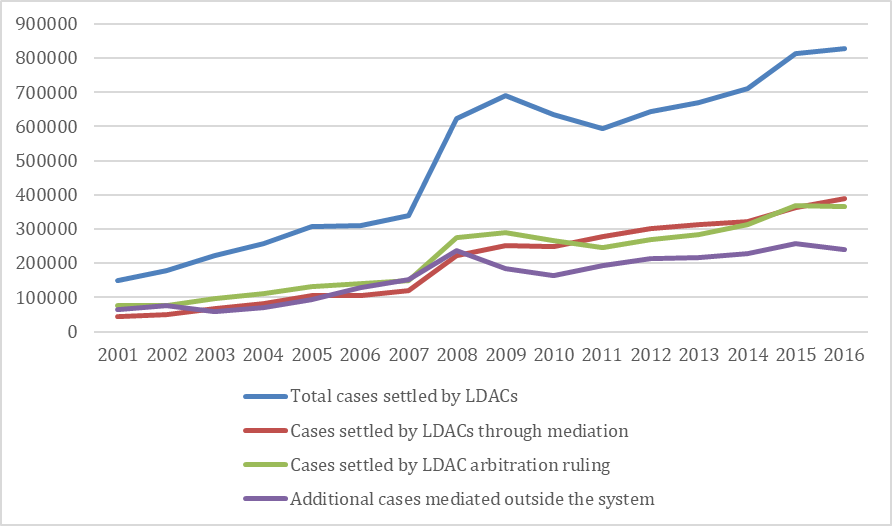

China has a four-stage process designed to resolve disputes between employees and their employer: consultation, mediation, arbitration and litigation. The key institution in this process is the local labour dispute arbitration committee (LDAC) which adjudicates in the majority of routine labour disputes in China. Minor cases might also be handled by the local government’s labour and social security inspectorate, (劳动保障监察), an administrative office tasked with ensuring employers’ compliance with labour law and regulations. It is relatively straightforward and inexpensive for workers to apply for arbitration and most cases are dealt with as quickly as possible. However, LDACs will only accept cases where the plaintiff can prove a formal labour relationship with the employer, effectively excluding workers in the informal economy, workers discriminated against in the hiring process and those over the retirement age who are no longer officially considered workers. Civil servants and military personnel are also excluded from the arbitration process. Arbitration claims have to be filed within one year of the dispute arising, which can be a major problem for victims of occupational diseases such as pneumoconiosis, who very often do not realize they are ill until several years after they left their employment. The vast majority of disputes accepted by LDACs are related to remuneration, social insurance payments and contract termination, with a smaller proportion of work-related injury cases. The outright win percentage for workers in 2016 was around 35 percent while about 45 percent of cases resulted in a compromise ruling, according to the China Labour Statistical Yearbook.

Number of cases settled by China’s labour dispute arbitration committees (2001-2016)

* The spike in the number of cases in 2008 coincided with the introduction of the Labour Contract Law and the Labour Dispute Mediation and Arbitration Law which gave workers additional ability and incentive to seek legal redress for labour rights violations.

Generally speaking, workers can only take their grievance to the civil courts after the LDAC has made a ruling. If a court does accept a labour dispute case, it will be handled in accordance with civil litigation procedures. In most labour dispute litigation cases, the burden of proof lies with the employer - see the Supreme People’s Court’s 2001 Labour Dispute Interpretation (最高人民法院关于审理劳动争议案件适用法律若干问题的解释), which states that the employer shall have the burden of proof in cases where the dispute arises from an employer’s decision to terminate an employee, reduce remuneration or re-calculate length of service. The disadvantage for worker plaintiffs is the financial cost and time taken up by court proceedings. Even in the most straightforward of labour dispute cases, workers will have to pay legal fees of at least 5,000 yuan. Employers can hold up cases by endlessly appealing decisions to a higher court, and, even if the plaintiff does win, there is no guarantee the judgement will actually be enforced. Given the huge backlog of cases they have to deal with, courts (like the LDACs) often seek to resolve disputes through mediation rather than formal judgements and this can adversely affect workers’ basic rights. Courts and LDACs are reluctant to take on collective cases and often break them down into individual plaintiffs. Chinese courts will not accept class action law suits.

How do local governments respond to collective labour disputes?

The reluctance of the LDACs and civil courts to accept collective labour disputes, combined with the lack of any formal collective bargaining mechanism in China (see above), means that workers usually have no choice but to take collective action in a bid to resolve their grievances. By taking collective action and publicising that action on social media, workers can often force local government and trade union officials to respond. However, the response is not always helpful. The majority of collective disputes in China are related to the non-payment of wages. The problem is endemic in the construction industry but is also widespread in manufacturing and service industries. In most of these cases, local officials will put pressure on the employer (if they can be located) to pay at least a portion of the wages owed and then persuade the workers to accept the deal. Local governments and trade unions routinely brag about the amount of money they have recovered for workers, without ever really explaining how they allowed the wages to go unpaid in the first place. In strikes and protests over pay, benefits and working conditions, local officials will again often put pressure on both workers and management to reach a mutually acceptable compromise deal and get striking workers back to work as soon as possible. However these quick fixes rarely address the underlying causes of the dispute, and as a result it is not unusual for another strike to break out six months or a year later. It is quite common for police to be dispatched to the scene of a strike but their primary role in these situations is one of containment, ensuring that the protesters do not leave the workplace or in any other way disrupt public order. According to data from CLB’s Strike Map, arrests are only made in about five percent of cases and if workers are detained by police, they are usually released within a few hours or a few days at the most.

Is there a minimum wage in China and is it a living wage?

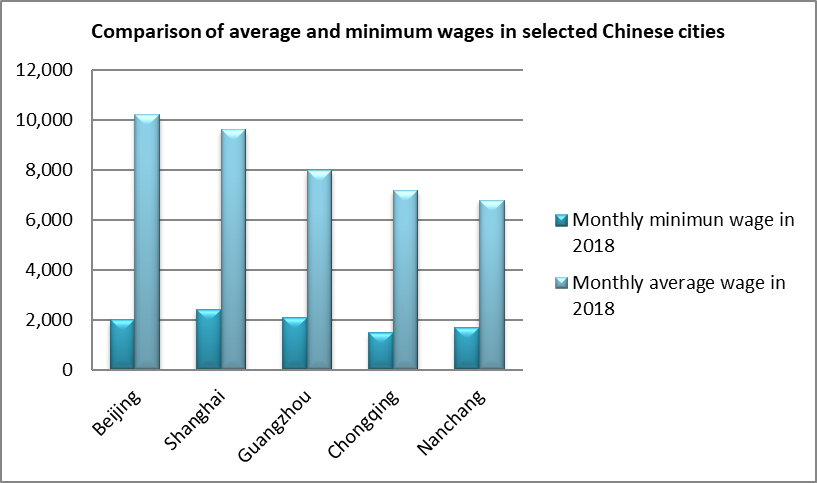

There is both a monthly and an hourly minimum wage in China. Minimum wage rates are determined by regional governments, based on local living costs, local wages and the overall supply and demand for labour. As a result, there is a considerable variation between the minimum wage levels in major cities and in poorer rural areas. The highest monthly minimum wage in July 2018 was in Shanghai (2,420 yuan), which was roughly double the minimum wage in smaller cities in provinces such as Hunan, Hubei, Liaoning and Heilongjiang. The minimum wage is usually adjusted every two years, although local governments are not legally required to do so. Indeed, in 2017, the provincial government of Guangdong decided to only adjust its minimum wage every three years in a bid to slow the outflow of business from the region to other countries and the Chinese interior. Several other provinces may follow suit.

National government guidelines stipulate that the minimum wage should be at least 40 percent of the local average wage. In reality, the minimum wage is usually only between 20 and 35 percent of the average wage, barely enough to cover accommodation, transport and food costs. Workers on the minimum wage, including most production line workers, unskilled labourers, shop workers etc. have to rely on overtime, bonuses and subsidies in order to make a living wage. As a consequence, if the employer cancels or reduces overtime, bonuses and other benefits, low-paid workers will often demand immediate restoration. Likewise, workers on the minimum wage are determined to ensure that every last cent of what they are owed is paid in full if and when they are laid off.

Is precarious work a problem in China?

Precarious work and the casualization of labour is an increasingly serious issue in China, just as it is in more developed economies. Some industries, such as construction, have relied on casual labour for decades but ever since the introduction of the Labour Contract Law in 2008, more and more employers have sought to get around their legal obligations by reassigning permanent staff as short-term or agency workers with fewer benefits. The rapid development of the gig economy in China means that many workers are now hired as “independent contractors” rather than formal employees. Many of these new jobs are poorly paid, insecure and require employees to work long hours in often dangerous conditions. Delivery drivers and couriers, for example, are at constant risk of traffic accidents but are often not fully covered by their medical insurance policy (if they have one) and have to pay a large proportion of their medical bills out of their own pocket.

Do Chinese workers have a reliable social welfare safety net?

The days of the “iron rice bowl” (guaranteed employment, housing, healthcare and pensions) for urban workers are long gone – for rural residents, they never existed at all. In its place, the Chinese government has sought to create a new social security system that would make employers and, to a lesser extent, employees responsible for contributions to pensions, unemployment, medical, work-related injury and maternity insurance. In addition, the government established a housing fund designed to help employees, who no longer had housing provided for them, buy their own home. These contributions are pooled in social insurance funds managed by the local government, which are supposed to be used only for their designated purpose. In general, enforcement of even the most basic provisions of the social insurance system has been very lax, with the majority of employers failing to fully comply with their obligations. Non-compliance is so common in fact that the head of e-commerce giant JD.com felt the need to brag about the fact that his company had actually paid its 157,831 full-time staff more than six billion yuan in social insurance contributions in 2017. The government is seeking to resolve the social insurance shortfall by introducing new pension and medical insurance schemes based on individual contributions from urban and rural residents, and by gradually reducing the contributions employers have to make in the hope more will comply. In the meantime, tens of millions of workers still lack proper pensions and medical insurance and will have to rely on their family for support in their old age. For more details, please see our comprehensive introduction to China’s social security system.

A version of this article was first published in December 2014. It was last updated in July 2018.