China’s workers had little reason to cheer when the government announced today that the economy rebounded last year, growing by 6.9 percent in 2017, well above the official target of “about 6.5 percent.”

Higher economic growth last year merely created more low-paid and insecure jobs, especially in the rapidly expanding service sector, while factory workers continued to be laid off, often without any compensation, and construction workers fought a constant battle against wage arrears.

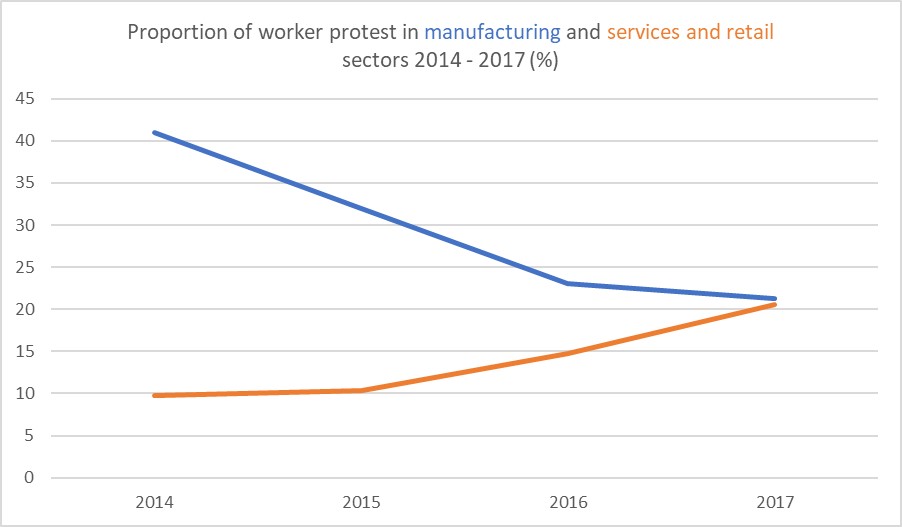

An analysis of the more than 8,000 incidents recorded on CLB’s Strike Map from 2014 to 2017 shows that the proportion of service and retail sector protests has increased steadily over the last four years, reaching 20.6 percent last year, as the proportion of protests in manufacturing, once the epicentre of worker activism in China declined from 41 percent in 2014 to 21.3 percent last year (see graph below).

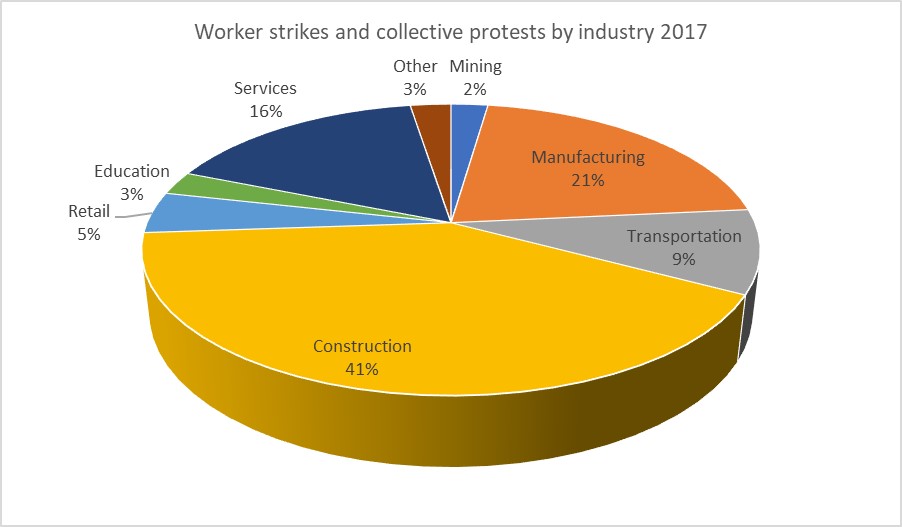

The construction industry, long plagued by wage arrears and dangerous working conditions, is now the main source of worker discontent and activism, accounting for 41 percent of the 1,255 worker protests recorded last year, while protests in the mining sector fell noticeably, suggesting that coal mining industry might be recovering after a long period of decline.

The private sector was a notable focus of labour unrest in 2017, accounting for 65 percent of all incidents, compared to around 55 percent in each of the three previous years. Wage levels for workers in the private sector have for many years been the lowest in China, lagging some 40 percent behind workers in foreign-owned firms, and around 30 percent less than workers in state-owned enterprises in 2016, according to official statistics.

But even in state-owned enterprises, which posted record profits in 2017, many workers have yet to see the benefit. Millions of SOE workers are employed as agency labour with lower pay and fewer benefits than formal employees. There were several high-profile disputes over unequal pay involving agency workers last year, including the Handan coal miners, state infrastructure construction workers in Kunming, and one of the most remarkable worker campaigns of 2017, the FAW-Volkswagen workers in Changchun.

There was surge in the number of protests in the hotel, catering and leisure industries, which have notoriously low pay levels and very little job security. Workers in the rapidly growing gym business were also particularly visible in demanding pay and other benefits from their employer.

There were also more protests in the traditional retail sector, which has been struggling to compete against the rise of ecommerce platforms. There were a dozen protests in supermarkets alone last year, mostly resisting sudden closures without compensation. For a closer look at worker conditions and organizing in one of China’s retail giants, see CLB’s report on Walmart workers in China.

Workers in the new service economy such as drivers for food delivery companies and ride- hailing apps also staged regular protests, usually over low pay levels, excessive work hours and wage arrears. Strikes and protests by drivers in food and other delivery services accounted for 21 percent of all collective actions in the transport sector where protests have been dominated in the past by taxi drivers.

Medical workers, including doctors, nurses, and other hospital staff, accounted for ten percent of all service sector collective actions, with workers usually protesting employment status and low pay.

Although not as willing to take collective action as blue collar workers, white collar workers had very low levels of job satisfaction in 2017, according to a report by recruitment agency Zhaopin. Workers complained of long hours, low pay, and no time to rest. The report said about 85 percent of white-collar workers had to work overtime every week, and 21.3 percent had to work five to ten hours overtime each week.

Regionally, worker protests continued to shift inland and away from Guangdong, the traditional hotbed of worker unrest in China. While Guangdong still accounted for 12 percent of all worker protests in 2017, that proportion has dropped steadily from almost 22 percent in 2014, while inland provinces like Shaanxi, Henan and Anhui doubled their share of worker actions over the same period.

Please note, the number of incidents recorded in 2017 is about half the total in previous years. This simply reflects a change in CLB’s sampling methods. In the absence of any official government figures, we estimate that the actual number of protests is roughly the same as in 2016.