On 26 September, 17 construction workers were reported missing after a mudslide swept through the shed in which they were living in Ya’an, Sichuan. As of 27 September, rescue teams had found ten out of 17 missing workers. Of those ten, two had suffered injuries, and seven were found dead.

The Ya’an meteorological bureau had issued a yellow warning at 4:00 pm on 25 September, stating that the area was at high risk of experiencing a geological disaster. One worker living nearby said that heavy rains had started at 8:00 pm. A colleague of his saw the mudslide sweep through the shed in which the workers were living, destroying the first floor in an instant.

Because roads were blocked by landslides, the fire brigade only arrived at 9:00 the next morning. Sichuan’s fire and rescue forces dispatched over one hundred people, two dogs, and 27 vehicles in the rescue effort. Even the central government got involved, with the Vice Minister of Emergency Management, Huang Ming, playing a coordinating role.

Yet this is far from the first time construction workers have perished in disasters. In June, floods trapped 14 construction workers in a tunnel in Zhuhai, Guangdong, all of whom were later found dead. The next month, despite the local meteorological office issuing a warning, workers were still expected to go to work in Henan, where hundreds died in flooding.

When these types of disasters take lives, the central government orders local authorities to improve their emergency response. But these reactions are focused on what to do once disasters have occurred, rather than how to mitigate the possibility of workers being put in danger in the first place.

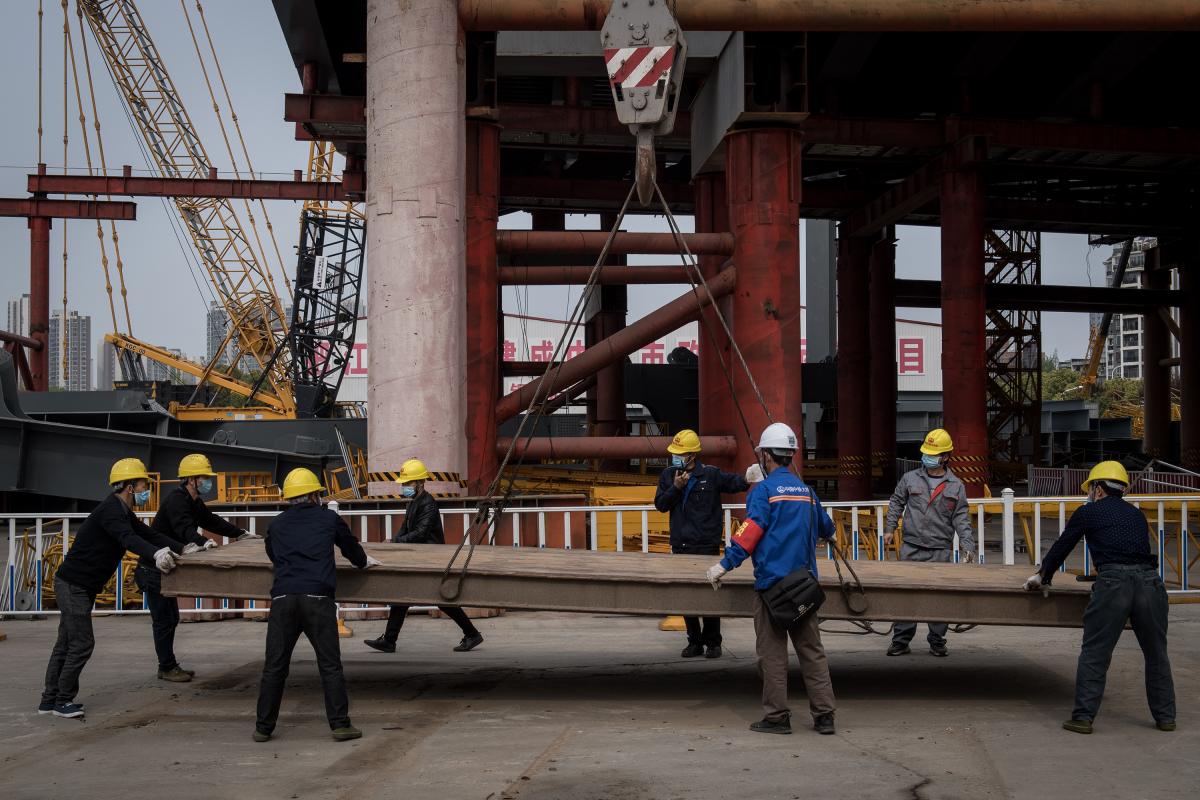

What if these events were not treated as emergencies, but as situations in which many workers commonly find themselves? Construction has long been one of the most dangerous industries in China. CLB’s Work Accident Map shows that there have been 117 work-related accidents in the construction industry this year, many of them resulting in fatalities. In CLB’s interviews with construction workers, one of them noted that the elevators used to scale the high-rise under construction were unstable. Migrant workers are often housed in poor-quality accommodation. Before they arrive on sites, workers often do not know how unsafe conditions can be.

Disasters are difficult to predict, but decreasing the likelihood that they take lives is possible. The provincial government announcement that lays out the overall response in Ya’an mentions conducting investigations into construction sites and their risks. But one-off investigations will not identify all risks.

Workers on-site are best placed to know if they are working in unsafe conditions. Channels for workers to report hazards without fear of retribution or loss of pay could go a long way in making sites safer. For instance, a worker living nearby the site in Ya’an said that due to the construction of a tourism route, the mountain roads were uneven, which deterred a potential rescue effort on the night of the mudslide.

Given the rapid advancement of climate change, it’s increasingly likely that areas around China will be hit by heavy flooding. Without changing the mechanisms by which workers can report threats to their safety, workers will continue to work under potentially life-endangering conditions.