A student at Sun Yat-sen University filed a gender discrimination complaint in February with the Shenzhen Human Resources Bureau, arguing that job postings on Zhaopin, China’s biggest online employment platform, discriminate against female job seekers. When the student, Xiao Zhou, visited Zhaopin’s recruitment office in Shenzhen, she ran into numerous job postings with restrictions reading “men only”, despite the company’s attempts to stop such advertisements.

“I am angry,” says Zhou, “I hope that by taking action, I can bring about some change so that our society can strengthen its stance on gender discrimination in the workplace.”

8 March is International Women's Day, and many women like Zhou are fed up of such abuses and are ready to take action. The rise in gender discrimination cases have made their way to China’s top court, which last August issued a briefing on gender discrimination.

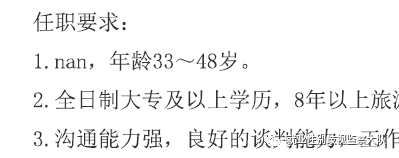

Employer bypasses Zhaopin requirements in job ad by using pinyin "nan" instead of Chinese character 男 for ”male“

A new report by none other than Zhaopin, the employment platform entangled in Xiao Zhou’s case, released a new report on Monday documenting gender discrimination in employment and advancement in the workplace. Zhaopin’s “2017 Report on the Current Situation of Chinese Women in the Workplace” collected responses from over 128,500 workers on questions ranging from employment opportunities to career development.

According to the study, 22 percent of women report severe or very severe discrimination when seeking employment, while 14 percent of men raised the issue. Employers across China often state a gender preference in job postings, even indirectly as in Xiao Zhou’s case, and women are sometimes asked about family planning when applying for jobs.

White-collar, college-educated female job hunters like Xiao Zhou don't seem to have an advantage, survey respondents say. Compared to men, higher-level graduates are more than twice as likely to be discriminated against when they applied for jobs, with 43 percent of female graduates encountering severe discrimination, according to the Zhaopin report.

A separate 2015 survey by All China Federation of Women showed that 87% of women graduates experience some kind of employment discrimination, with the vast majority citing unfair preference for men as the cause.

Such explicit discrimination has faced pushback from courts in recent years. Xiao’s complaints, like earlier, more high profile cases, tend to deal exclusively with overt discrimination faced by women, glossing over other, more subtle ways in which discrimination shows up.

Gender discrimination in the workplace is often a much more pervasive phenomenon: when surveyed, about 40% of women believed that they lacked the competence or experience required for being promoted, compared with 32% of men. Men were more likely to cite external factors, such as not being appreciated by their supervisors. Wider attitudes towards gender and work contribute to this belief, but women with equal qualifications and experience as men are much more likely to be passed up for promotion.

The odds are stacked starkly against women when it comes to career development and promotion opportunities. About 72% of Zhaopin survey participants had men as supervisors, compared to 28% with women as supervisors. The relative absense of women supervisors is directly linked to discrimination in promotions, with 25% of women experiencing severe or very severe discrimination in promotions, compared with 18% of men.

Despite the statistical evidence, often women have a hard time proving their claims in the legal system, since gender disparities are often subtle and hard to substantiate in courtrooms.

For more on gender discrimination in China and legal battles for equality, read Cao Ju’s 2012 suit against Beijing-based private tutor company Juren Academy and Ma Hu’s battle in 2015 with the Beijing Postal Service.