Two decades ago, the industrial heartland of the northeast was one of the main centres of worker activism in China. Workers staged numerous and widespread protests after being laid off with only minimal compensation from bankrupt and restructured state-owned enterprises. Some protests, such as those by laid-off oil workers in Daqing and metal workers in Liaoyang in 2002, involved tens of thousands of workers and lasted several weeks. These were seen by the authorities in Beijing as a significant threat to the state, and the government responded by arresting worker leaders and sentencing them to long prison terms.

Today, the northeast appears - on the surface at least - to be relatively quiet. Worker protests have spread across the whole country and into every sector of the economy, and it is Guangdong, Henan, Shandong and Jiangsu that are now the major centres of activism. The three northeastern provinces of Heilongjiang, Jilin and Liaoning together accounted for just 7.5 percent of the incidents recorded on China Labour Bulletin’s Strike Map in the last 18 months.

The protests in the northeast are no longer concentrated in the old state-owned industries, but in a diverse array of new privately-run service industries and the transport and logistics sector, which generally only offer low-paid and precarious employment with little or no social security benefits. These protests are mostly small-scale and fleeting. As such, they are not considered by the authorities to be a major threat. However, they reflect a deep-seated dissatisfaction and frustration with the lack of any real economic opportunity in the region. Already this year, some protests have turned violent and the government would be wise not to ignore the simmering unrest among workers who still remember the events of 18 years ago.

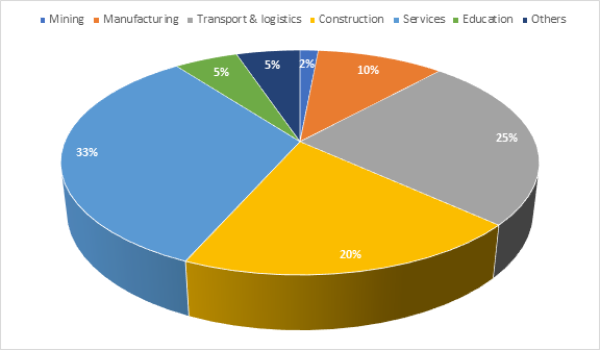

CLB’s Strike Map recorded 137 worker protests in Heilongjiang, Jilin and Liaoning from January 2019 to mid-August 2020. The service sector accounted for 33 percent of all these protests, and transport and logistics 25 percent, starkly illustrating the shift away from the region’s traditional industries.

Worker protests in northeast China since January 2019

In July, nearly 1,000 drivers from Harbin’s largest taxi company, Swan Taxi, staged one of the largest protests seen in Heilongjiang in the last five years. They were protesting the continued refusal of the company to return fees paid by drivers in exchange for the right to operate their taxis for a certain number of years. After years of complaints by drivers, the local authorities cancelled the fee system in 2017, but thousands of drivers who had already paid several years’ fees beyond 2017 are still waiting for refunds. The Swan Taxi protests led to drivers from two other companies in Harbin who faced the same problem also going on strike. The protests were given further impetus by the Covid-19 pandemic, which has severely impacted the taxi industry and left drivers desperate for any kind of income support.

The sports and leisure sector in the northeast has also been hard hit by the pandemic, and many protests by workers were directly related to the closure of gyms and fitness centres that can no longer afford to stay open after restrictions were lifted. On July 28, for example, a gym in Changchun suddenly closed and the owner disappeared, owing staff wages and customers membership fee refunds. There have been several similar cases across the northeast over the last few months, with both employees and customers left out of pocket.

In the former industrial cities of Liaoning, the catering and hospitality industry has absorbed many workers laid off from state-owned enterprises. Yet this sector, too, suffered a big blow from the pandemic, leading to numerous disputes with workers over unpaid wages. On 16 June, the employees at Morin Khuur, a privately-owned Mongolian-themed resort and restaurant in Panjin staged a protest demanding the payment of wages in arrears owed since late 2019. In an echo of the state-owned industry protests in the 2000s, the workers claimed that the local government was colluding with the company owners rather than protecting the rights of the workers.

The construction industry - which accounted for 42 percent of all protests across China over the same period - only accounted for 20 percent in northeast China. This suggests a relative lack of new construction and infrastructure projects in the region, which recorded negative economic growth in the first half of 2020.

Mining, traditionally a major industry in the northeast, only saw two protests over the last 18 months. One of the last major incidents occurred in March 2016 when, in a throwback to the early 2000s, thousands of angry coal miners in Shuangyashan staged weeks of strikes and protests that eventually forced the local government to pay months of wage arrears owed by their employer, the state-owned Longmay Group.

Those protests were triggered by claims made by Heilongjiang Governor Lu Hao during a press conference at the National People’s Congress in Beijing that none of Longmay’s employees were owed any back pay. On 12 March 2016, Lu Hao finally admitted that he had been mistaken about the wage arrears situation at Longmay and that the local government had promised to pay the wages owed for November and December. By 15 March, workers said that most of their January wages had been paid and that their February wages would be paid soon.

The northeast has also long been the centre of large-scale protests by retired teachers and community teachers who have been denied their promised welfare benefits by local government officials. There are still occasional protests, but the last major incident occurred in Beijing in January 2018, when teachers from all over China - but primarily the northeast - gathered in the capital to demand payment of long-delayed pensions and other benefits.

The state-owned industries in the northeast have now largely been consolidated into a much smaller number of more profitable and sustainable enterprises. However, protests in the state sector do occasionally occur, most notably in November 2016, when around 3,000 agency workers from FAW-Volkswagen, a Sino-German car manufacturing joint-venture in Changchun, embarked on a long campaign demanding equal pay for equal work. Some of them, hired by employment agencies on behalf of FAW-Volkswagen, had been working at the company for more than ten years but claimed they were only paid half as much as directly employed workers. The workers eventually won a partial victory, but only after their representative, Fu Tianbo, had been detained for more than a year on charges of “gathering a crowd to disrupt public order.”

The authorities’ treatment of Fu Tianbo was, however, considerably less draconian than that meted out to Yao Fuxin and Xiao Yunliang, the two leaders of the Liaoyang Ferro-Alloy Factory protest, who were sentenced to jail terms of seven and four years, respectively, for subversion. The Liaoyang Ferro-Alloy protest in the spring of 2002 was one of the best-known examples of worker activism at the time. But as noted above, it was just part of a wider movement of laid-off state-owned enterprise employees, in Liaoyang and across Liaoning, as well as the northeast as a whole.

Then, as now, the workers had very basic demands: the payment of wages in arrears from bankrupted enterprises, pensions and other welfare benefits they were legally entitled to. Then, as now, the local government and official trade union did little or nothing to help the workers defend their rights and often sided with management in labour disputes.

The All-China Federation of Trade Unions pledged in 2018 to organize workers in the transport and service industries that are now the focus of worker protests in the northeast of China. However, there is very little evidence of the union doing anything to help these workers. The Heilongjiang taxi drivers, gym employees in Jilin and hospitality industry workers in Liaoning are running out of patience, and the local government and trade unions need to listen to and act on worker grievances before it is too late.