photo: humphery/ Shutterstock.com

Note: China Labour Bulletin recently published our healthcare workers' report: Unprotected yet Unyielding: The Decade-Long Protest of China’s Healthcare Workers (2013-2023).

This chapter explains the salary and performance of medical staff, especially the issue of reduced income and uneven distribution of subsidies during Covid 19. It also points out the issue of nurses’ wages falling and hospitals being more willing to invest resources in doctors.

The Strike Map includes 14 income-related incidents, 13 of which occurred in public hospitals and the remaining one related to arrangements after a public hospital's restructuring. Healthcare workers protested low wages, deductions of performance pay, or unfair distribution of subsidies.

The remuneration of medical staff in public hospitals consists of three parts: basic wage (基本工资), performance pay (绩效工资), and allowances and subsidies (津贴补贴). The ratio of basic wage to performance pay varies from 30:70 to 40:60 (performance pay is often more than the basic wage). Basic wage refers to a fixed monthly base salary, depending on the employee's length of service, title and position. Performance pay is allocated to departments based on the hospital’s income and balance from medical treatment, which is then allocated to medical staff based on workload and seniority. Generally speaking, the more treatment fees patients pay, the higher the performance pay of medical staff in that department.

A Caixin Weekly article describes how doctors in public hospitals are generally dissatisfied with their salaries. As described in Chapter 1 of this report, government funding for public hospitals is low, leading hospitals to rely on patient fees (including out-of-pocket payments and insurance payments). Also, public hospitals rely on drug markups as the price of medical services is set low. As a result, doctors are incentivised to order more prescriptions and tests for patients to increase hospital revenues and their own performance pay.

According to Caixin and the Beijing News (新京报), since 2009, the main direction of the healthcare reform policy has been to reduce the markup on medicines and consumables and raise the price of medical services so that the value of healthcare staff’s labour can be reflected, while reducing the overall healthcare expenditures of society. However, Caixin quoted a source close to a provincial health insurance bureau as saying:

“It is difficult to have a standard set of measurement and recognition of the value of healthcare labour, coupled with the fact that medicines, consumables, and inspections were the major part of the hospital’s income in the past, so reforms in the past have been put on hold.”

Performance pay has also led to an income disparity among staff in different departments. Caixin notes that paediatrics departments have very low prices for medical items due to the lack of major surgeries and tests and less difficulty in treating diseases, leading to low income for paediatrics staff. However, paediatricians’ jobs include serving children and comforting the parents. For the same examination and treatment items, they need more manpower and resources, and their emotional labour is greater. Therefore, paediatricians feel their labour is not paid off

Pay reductions and unfair subsidy distributions during the pandemic

During the pandemic, some departments’ revenue decreased, leaving staff with even lower pay and more dissatisfaction. On 17 September 2020, ten healthcare workers from the paediatrics department of the People’s Hospital of Susong (宿松县人民医院) in Anhui province jointly wrote a letter to the leadership requesting transfer to another post. As recorded in the CLB Strike Map, the staff were dissatisfied with the low performance pay, pointing out that in July 2020 the performance pay for paediatrics was 498 yuan (U.S. $71), while administrative staff received 2,600 yuan (U.S. $371). The workers’ letter said,

As a working person, the economy is the backbone and the foundation. Paediatric staff’s performance pay this month was even lower than that of formal employees who do not come to the hospital. How can we support our families?

On 24 September, the hospital responded by stating that in July, there were fewer paediatric visits, which was the reason for the lower performance pay. The hospital said it valued the staff’s demands and, taking into account factors such as the impact of the pandemic and the seasonality of children’s illnesses, decided that the July performance pay for paediatrics would be readjusted to the hospital’s average performance pay.

The CLB Calls-for-Help Map recorded five income-related incidents involving default on pandemic-related subsidies and performance pay. Four cases involved public hospitals, and one involved a private hospital. Hospitals quickly caused public outrage when they received subsidies from the central government but failed to pay them to their frontline workers as required. For example, in March 2020, several hospitals were exposed for unfair distribution of pandemic prevention and control subsidies. Administrative staff at Wuhan No. 5 Hospital (武汉市第五医院) received higher subsidies than rank-and-file healthcare workers, and board members of Ankang Central Hospital (安康市中心医院) in Shaanxi province received twice as much in subsidies as the hospital’s staff who went to support healthcare in Hubei province. The management team counted themselves in the list of frontline workers and favoured themselves in counting the number of days of attendance and the time spent on duty. Medical staff worked in shifts and worked longer hours than usual during the pandemic, but their attendance days were calculated based on a 24-hour day. As a result, they received less subsidies than the management.

After the public outcry, the State Council narrowed the definition of who could receive subsidies so that only workers who had “direct contact with confirmed or suspected cases” could be considered “frontline workers” eligible for subsidies. But this also backfired, as many pandemic prevention workers were excluded from the subsidised group. Online, many citizens engaged in medical and nursing work lamented:

More than a month of pandemic prevention, day and night, and all was in vain, not even a penny.

Some healthcare workers even mocked themselves on Weibo, saying they were “lucky” to be recognized as “frontline workers” because some patients they took care of tested positive. Other workers said that after the new policy was introduced, hospitals asked them to return the subsidies they had previously received.

In the dispute over the unfair distribution of pandemic subsidies, if local labour unions could compile the labour conditions and subsidy distributions of various hospitals and propose a more reasonable distribution plan to hospitals and local governments through collective bargaining, they would be able to meet the demands of workers rather than relying on the government to adjust its policies based solely on online public opinion and fragmented information. The latter approach may not be able to consider the specific situation of each locality and hospital.

China Labour Bulletin interviewed local trade unions about the unfair distribution of subsidies at the Ankang Central Hospital in Shaanxi, and trade union staff said they had visited the hospital to show concerns to the staff but could not put too much pressure on the hospital’s administration. The district union also said it could not negotiate with the hospital and the health system on behalf of frontline workers without a request from higher levels, believing that it would appear to have “no cause”.

While the union’s actions to sympathise with workers deserve recognition, if it can be more proactive, understand the needs and grievances of workers, establish a collective bargaining mechanism with hospitals, and discuss with the health department how policies can take into account the needs of workers, then the rights and interests of doctors and nurses can be more adequately safeguarded.

Nurses’ protest against performance pay system tilted in favour of doctors

The problem of lower service fees and pay is more serious for nurses than for doctors. The People’s Daily reported in 2016 that because public hospital service fees had not been adjusted for a long time, nursing service fees were low, with only about 10 per cent of the cost of nursing care being charged. Therefore, doctors were seen as able to directly create economic benefits for the hospital, while nurses would only add to the operating costs. Not only will many hospitals not increase nurses' income, but they are also reluctant to hire more nurses.

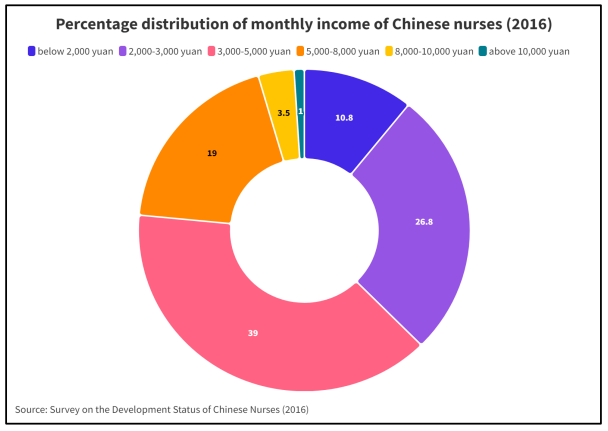

According to the Survey on the Development Situation of China's Nurses (中国护士群体发展现状调查), 83.7 per cent of nurses consider salary as the most important factor in their work. Most nurses earn a monthly salary of 2,000-5,000 yuan (U.S. $286-714, see chart below). According to the National Bureau of Statistics (国家统计局), the median disposable income of urban residents in 2016 was about 2,600 yuan (U.S. $371) per month.

The salaries of nurses are close to or even slightly higher than the median salaries of urban residents, but it should be noted that nurses, like other medical personnel, are paid a base salary and variable performance pay. When performance pay is drastically reduced, it tends to cause strong discontent among nurses.

The collective action cases aggregated by CLB show that some public hospitals have reduced nurses' performance pay to boost doctors' incomes in the process of healthcare reform, triggering nurses' protests. Of the 14 income-related collective actions, 10 were solely actions by nurses.

A protest in Nanyang, Henan

For example, on 6 June 2018, nurses at Nanyang City Centre Hospital (南阳市中心医院) in Henan province went on strike to protest the hospital’s performance pay reform plan. The incident occurred because, in May 2018, the hospital hired a third-party company to carry out reforms, which resulted in an upward adjustment in doctors’ performance pay but a two-thirds reduction for nurses’.

Photo: Nurses on strike at Nanyang City Centre Hospital in Henan Province Photo credit: Online publication, China Labour Bulletin archive

The hospital’s statement said that the reform was carried out in accordance with the instructions of the State Council and the National Health Commission on healthcare reform and hospital performance reform. However, the main direction of the healthcare reform policy is to reduce the drug and consumable markup and increase the price of medical services so that the value of medical personnel’s labour is reflected. Using a third-party company to do the accounting work, Nanyang City Centre Hospital initially promised a wage increase of ten per cent. This led nurses to question why their wages fell.

An analysis by the publication Medical Profession (医学界) said the problem could be due to new ways of determining performance pay with the healthcare reform. The piece said,

As the health care reform and the performance pay distribution system reform develops, the measurement of nursing work is more reflected in the intensity of work, time, and other quantitative elements. In the evaluation of factors such as technical difficulty, complexity, and risk, nursing positions are inevitably lower than clinical medical positions. Such a way of consideration will inevitably lead to a widening of the income gap between physicians and nurses.

An article in People of Traditional Chinese Medicine (中医人) pointed out that after the abolition or discouragement of drug markups, public hospitals lacked income and could only reduce expenditures. At the same time, nurses were numerous and of low status, so hospitals started by reducing their salaries.

There are many cases where the distribution of performance pay is skewed in favor of doctors, leading to protests by nurses, and in some cases, even doctors disagree with the hospitals’ practices. For example, in March 2015, nurses at the Children’s Hospital of Zhejiang University School of Medicine (浙江大学医学院附属儿童医院) went on strike because, while doctors and nurses of the same rank[4] originally received the same performance pay, the new program caused nurses’ performance pay to drop by 30 per cent, and nurses’ performance pay in some departments was nearly 2,000 yuan less (U.S. $286) than that of doctors of the same rank.

According to Dingxiangyuan, a doctor in the hospital said:

“The hospital intends to improve the treatment of doctors, but correspondingly reducing the performance pay of nurses is inappropriate and will inevitably incur the dissatisfaction of nurses.”

Another doctor said:

“Nurses in our hospitals are exhausted. I have seen nurses in the neonatal unit busy taking care of babies and mothers. They are very dedicated, and hospitals should give them equal treatment.”

After the nurses went on strike, surgical procedures were halted, no one was putting people on IV drips, and no one was dispensing medication. Eventually, the hospital board canceled the new program, and the nurses ended their strike.

To be continued.

Download the full report as a pdf here.

[4] Doctors and nurses are both divided into five ranks respectively.