The risks for construction workers on Cambodia’s notoriously unsafe building sites have been extensively documented. Less well-known are the dangers faced by workers in the cement industry, which has been providing the raw materials for Cambodia’s new shopping malls, skyscrapers and satellite cities. It is a business dominated by largely unaccountable Chinese-invested companies eager to cash in on the country’s ongoing building boom. Danielle Keeton-Olsen and Mech Dara investigate how the insatiable demand for cement is putting workers' lives in danger in the southern province of Kampot.

Just before his shift was about to end on 29 May, 60-year-old Var Sruoch heard a few pebbles falling around the site where his four-person team was crushing and drilling into limestone crags on the steep mountainside of Phnom La’ang in Kampot. Sruoch and a co-worker, who were resting some distance from the drilling, took off, running away from the landslide, but the two other workers were trapped.

As he was running, Sruoch turned back and saw huge boulders tumbling onto the spot where the two men were standing.

“I looked back and thought, ‘Oh with those rocks that fell, those two must have already died,’” he said. In addition to being his co-workers, the men who died, Kun Ral and Nheub Saron, were Sruoch’s cousins.

Sruoch has now retired from the cement industry he had worked in on-and-off for the last decade. His one memento of the industry is a denim shirt with the red octagonal logo of the China National Building Material Group and the words “Sino-Cambodian Huasheng,” which he said was a gift from the company managers on the day Ral and Saron died. (See photo below by Danielle Keeton-Olsen.)

Sruoch, Ral and Saron were part of a team contracted to break down the limestone rocks at Phnom La’ang for the Cambodian-Chinese joint venture Thai Boon Roong Cement. However, their project and work was overseen by the Kampot (C.K) Industrial Special Economic Zone (SEZ) under an unnamed Chinese manager. Companies within an SEZ in Cambodia are eligible for lower rates on taxes and customs, but the Kampot (C.K.) SEZ is not a registered business with the country’s Commerce Ministry.

Cambodia’s five registered cement companies have been vaulted to industry leaders by joint ventures with Thai and Chinese companies. The Battambang Conch Cement Co. Ltd. in the western province of Battambang is a joint venture between Cambodian tycoons and the Hong Kong-based Conch International Holdings, while Cambodia Cement Chakrey Ting Co. Ltd., also in Kampot, is majority-owned by the Shanghai-listed Huaxin Cement Co. and financed by the Bank of China.

Thai Boon Roong became the nation’s newest cement plant after its inauguration in November last year. With a production rate of 2,500 tons of cement per day, the factory will lift Cambodia’s cement output to eight million tons in a year, the Mines and Energy Ministry boasted at the inauguration ceremony.

The responsibility for mining and processing the 4,000 tons of limestone each day needed to meet the cement demand went to another Cambodian-registered joint venture, Sino-Cambodia Huasheng Engineering Co. Ltd., which is chaired by a Chinese national named Mo Tao. However, the company’s registered address on Phnom Penh’s Street 160 seems not to exist, and calls to their one Cambodian phone number were never answered.

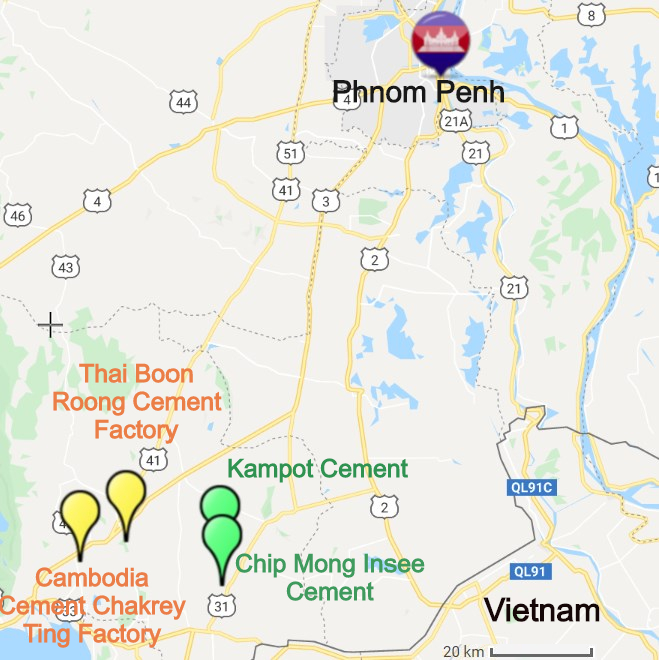

Cement factories located in Kampot province, south of Phnom Penh

This sprawling network of largely unaccountable companies and subcontractors in the cement industry creates headaches for the poorly-trained Cambodian government inspectors who often ignore the subcontractors entirely.

Even though inspections are required by law, Khun Tharo, program manager for the labour rights group Central, said they rarely take place.

“There are concerns that, one, is that the labour inspectors are not professionally trained, and, second, is the corruption, and there's not enough labour inspectors to carry out that many inspections,” Tharo said.

Both in the cement industry and the larger construction sector, the Ministry of Labour and Vocational Training tends to react only to serious workplace injuries or fatalities, rather than proactively prevent them, Tharo said.

The Labour Ministry has carved out specific occupational health and safety protocols for garment and brick factory workers, but the country has yet to set any standards in the construction industry, which is largely informal. But even if policymakers are not considering special protections in the construction sector, Tharo suggested that registering cement industry subcontractors — and thereby registering workers with Cambodia’s National Social Security Fund (NSSF) — would be a positive first step for health and safety in the construction sector.

Interviews with workers at the Chakrey Ting cement factory, about 15 kilometres west of Thai Boon Roong’s campus in Kampot, suggest that the industry’s health and safety problems are not restricted to the limestone quarries.

Chakrey Ting, incidentally, has a long history with China dating back to the 1955 Bandung Conference in Indonesia, which first marked the People’s Republic of China’s emergence as a potential leader of the Global South. The following year, Cambodia’s ruler Norodom Sihanouk, paid a state visit to Beijing and asked for material aid and assistance in the construction of industrial facilities, of which the Chakrey Ting Cement Factory was one. The factory, the first of its kind in Cambodia, was established in 1961 with the help of experts from China’s Huaxin Cement. The factory was known in the mid-1960’s as the Liu Shaoqi Cement Factory, after the then president of the PRC, and was upheld as an enduring symbol of Sino-Cambodian friendship.

Following decades of war and political turmoil in Cambodia, the facility was rebuilt in 2012 with a US$100 million investment from Huaxin Cement and went into production in 2015. The factory was once again upheld as an example of China’s role in international development as part of paramount leader Xi Jinping’s Belt and Road initiative.

From the porch of his 1950s-style rented room just outside the Chakrey Ting factory, Kheam Seth shows a video of his daily work: ushering 50-kilogram cement bags off a conveyor belt and into neat piles in a truck. His boss, an unregistered subcontractor for the factory, provides masks or krama, checkered scarves common in Cambodia, to prevent workers from breathing in cement dust, but Seth said his hands and ankles are constantly covered in the white powder and he often struggles to breathe.

Tit Sovannara, a friend of Seth’s who stops by to chat with the worker, is formally employed by the Chakrey Ting company, so he earns a better salary for his job of monitoring the cement mixing process, and he receives NSSF coverage. However, he decided not to use his company-provided insurance after he realized it required several forms of permission and approval from his employer.

Fields surrounding the Chakrey Ting cement factory in Kampot. Photo by Danielle Keeton-Olsen

Workers suggest that accidents are easily covered up, especially in subcontracted gigs that skirt both taxes and payments to the NSSF scheme.

A few weeks before he documented and disseminated the news of the deaths of Ral and Saron, Khem Phath, a construction worker and organiser at Thai Boon Roong for the Building and Wood Workers Trade Union Federation of Cambodia (BWTUC), said he found out that two construction workers, both Chinese nationals, had been killed when a warehouse collapsed beneath them as they installed its roof. Phath said Thai Boon Roong had not informed the other workers on the construction team of this incident. It occurred on a Sunday, when fewer people were working, and Phath only found out about it from a security guard.

Thai Boon Roong announced at its inauguration that just ten percent of its nearly 350 employees were foreign nationals. Conversations with workers suggested that their managers, both within the cement company and its subcontracted entities, were predominantly Chinese nationals. This adds to the problems for the sub-contracted workers because they find it almost impossible to communicate with their Chinese bosses.

Uon Channa, another Thai Boon Roong construction worker and local organiser for BWTUC said most of the time the workers do not have a translator to interpret their managers’ instructions, and, as a result, the bosses will scold them or push them to work overtime.

Reflecting on the fatal 29 May accident, Sruoch said he had had a strange feeling about going to that particular quarry on that day. Working in limestone mining on-and-off for more than a decade, Sruoch knew the rock would be more unstable during the transition into the rainy season, but he felt that even if he could speak Chinese, his former boss, who was always urging speed, wouldn’t listen to his hunch.

Two years prior, another retired worker, Ya Sophath, said he narrowly escaped the same fate as Ral and Saron. While he was drilling into a karst as a subcontractor for Cambodia Cement Chakrey Ting, he heard the same sinister sound of dropping pebbles, only to watch a boulder the size of his farmhouse fall near him and his team.

“If we had moved to the right, we would have been finished,” he said. “Luckily, we moved to the left.”

Today, 47-year-old Sophath lives and works between the mountain and the cement factory, growing leafy greens with his wife and children to sell in local markets. He said the salary was better at the factory, but not worth the risks, which he did not realise he was taking until it nearly ended his life.

Danielle Keeton-Olsen is a journalist based in Phnom Penh, focused on environmental issues, labour rights and the economy. She also works as an editor for the Phnom Penh news site, VOD English.

Mech Dara is a Cambodian freelance reporter predominantly covering politics and human rights issues. He previously reported for the nation's English newspapers, the Cambodia Daily and Phnom Penh Post.

This article is part of an occasional series commissioned by CLB designed to examine the influence of Chinese capital around the world and foster worker solidarity in the Global South.