Photo credit: humphery / Shutterstock.com

Letter from the Editors

China’s average weekly working hours in June this year was 48.6, according to the National Bureau of Statistics. This number exceeds the "six-day, eight-hour" workweek. China’s average weekly working hours have increased from 45.5 hours in 2015 to 49 hours in 2023. Excessively long working hours directly damage the health of workers. Workers would also suffer from poor work-life balance.

Currently, many Chinese manufacturing workers face long working hours and low wages. At the same time, they are worried that factories will be relocated, that their income will be lowered due to reduced orders, or that they will not receive severance pay when the factory closes. The major issue here is to ensure that workers receive reasonable wages within standard working hours and to protect their legitimate rights and interests during factory relocations. Such issues should be a core focus of supply chain due diligence.

Thanks for reading.

CLB editors

Workers’ Voices

Photo: workers protested at the administrative office of the Akcome factory in Huizhou, Zhejiang

Workers protest furloughs by solar panel company Akcome with living allowance below minimum wage

"Basic salary 1,720 yuan × 70% — about 600 yuan by deducting the social insurance and housing fund, and we are not allowed to take other jobs. How can we live like this?"

–said a worker of Akcome Technology

Solar panel manufacturing has faced major upheavals, and a listed company Akcome Technology announced furloughs in three factories with unreasonable restrictions on workers. During furloughs, workers were only paid 70% of the basic salary (which is below minimum wage) and had to pay for their social security contributions, housing provident fund, personal income tax, and dormitory utilities. In addition, workers could not take other jobs or their payments would be cut. This puts workers in a dilemma: they must either accept a few hundred yuan per month while waiting to resume work, or find another job and forfeit any severance payment since they voluntarily resign.

Workers refused to accept such arrangements and protested at the administrative office of the factory in Huizhou, Zhejiang. A worker said,

"It's a shutdown, an unreasonable long-term holiday arrangement, forcing people to leave without wanting to pay compensation. We ask every worker who sees this to spread the word."

Moreover, the company’s hasty announcement showed a lack of negotiations with workers and trade unions as required by the law. Workers also reported issues of wage arrears. Please see CLB’s article for full details.

Strike Action

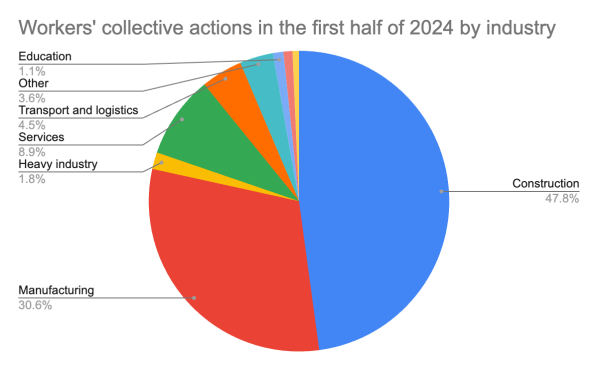

Construction and manufacturing are the sectors with the most protests in the first half of 2024. China Labour Bulletin's Strike Map has completed the case collection for the first half of 2024, with a total of 719 incidents recorded, an increase from 696 incidents in the same period in 2023. The largest proportion of protests remains those by construction workers demanding wages, with 344 incidents collected (47.8%), similar to last year's 320 incidents (46.0%). Protests in manufacturing and heavy industries over wage arrears, factory relocations, and closures totalled 233 incidents (32.4%), slightly higher than the 197 incidents (28.3%) in the same period in 2023, reflecting the ongoing situation of factory relocations, closures, and production reductions in coastal manufacturing industries such as electronics and garment factories.

As for the service industry (62 incidents, 8.62%) and logistics industry (32 incidents, 4.45%), worker protests were lower than last year (97 and 55 incidents, respectively). The higher number of cases collected in the service industry in 2023 was mainly due to closures of two chain department stores, Better Life and Carrefour. The decrease in the logistics industry incidents was because the taxi drivers’ protests this year were mainly against ride-hailing services and electric bikes, with fewer protests demanding management rights.

There were also 8 incidents in the education sector and 6 in the party and government institutions (accounting for approximately 2% in total). Most of these incidents were teacher strikes due to dissatisfaction with wage arrears. In northern and northeastern China, wage arrears in some government-related institutions such as forestry farms, water companies, and grain bureaus also sparked protests.

Photo: taxi drivers surrounded a ride-hailing vehicle in Zhangjiakou, Hebei

Taxi drivers protested against ride-hailing competition in four regions. On 30 June, taxi drivers in Ganzhou, Jiangxi Province, issued a petition citing a decline in business due to competition from ride-hailing and illegal cabs. They requested that the airport police increase security at the exits to protect the legal rights of regular taxis. The petition was signed by at least 50 drivers. The drivers reported that "illegal cabs have increased, especially at airports and train stations, where drivers rampantly compete with taxis for passengers". Taxi drivers proposed "organizing volunteers at airports and train stations to act as order maintainers and assist the transportation management in discouraging illegal cabs."

Similarly, on 19 June, drivers in Wuhai, Inner Mongolia, submitted a petition to the transportation bureau against the policy of integrating ride-hailing with traditional taxis (巡网融合). Drivers demanded that platforms must commit not to dispatch orders to private cars and that platforms should be supervised by the government. They also encouraged their colleagues and citizens to report illegal cabs and ride-hailing vehicles.

Taxi drivers went on strike to protest ride-hailing competition in Yulin, Shaanxi Province on 12 June. The strike lasted for three consecutive days, with grievances such as high gas prices and low operating fares. But the top complaint was still against ride-hailing services. The drivers were dissatisfied with many employees using ride-hailing to earn extra income after work, effectively competing with taxi drivers and reducing their income. In Zhangjiakou, Hebei Province, taxi drivers surrounded a ride-hailing vehicle on 20 June, demanding to check for evidence of ride-hailing and got into a dispute with a police officer.

Workers’ Requests for Help

A high school senior intern worked nearly 12 hours daily, suffered a sudden cerebral haemorrhage and was hospitalised. On 8 June, an intern worker, employed at Smiss Technology Co., Ltd. in Shenzhen, suffered a sudden cerebral hemorrhage and was hospitalised. The worker Li (a pseudonym) is a student at Zhanjiang Wuchuan Haibin Middle School (located in Wuchuan, Guangdong), and was placed as an intern through Changlong Labor Dispatching Company in early 2024. Li’s work included assembling electronic products, packaging, labelling, and testing. The salary was set at 15 yuan per hour, with an overtime rate of 16.5 yuan per hour.

Li's pre-internship medical report was normal. His family reported that he had expressed dissatisfaction with excessive overtime work and wanted to leave the factory. His fellow intern Wang also said that Li endured nearly 12-hour workdays assembling electronic cigarettes. Although the interns wanted to leave, they were forced to stay as the school would only issue diplomas if students completed the required hours. In March, Li wanted to take sick leave due to a fever but was denied by the school and the factory. By April, Li decided to forfeit his diploma and leave the factory early. The school agreed but still delayed his departure. The contract revealed by a parent of another intern showed that workers had to work 12 hours a day, despite the factory’s denial. The Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security in Shenzhen confirmed that the factory did arrange overtime for workers both on weekdays and weekends, which violated the law. The latest condition of Li and the penalties to the school, the company and the labour agency were unannounced.

Overloaded Cargo Orders Pose Challenges for Truck Drivers. In June, truck drivers across various provinces and cities expressed their difficulties: on-demand delivery platforms such as Lalamove and Yunmanman did not prevent them from receiving overloaded cargo orders. If a driver cancelled an order due to illegal overloading, the platform would deduct “behaviour points,” affecting future orders and commission income and even restricting the drivers’ withdrawal of cash. For instance, Mr. Chen from Shenzhen said there were few orders that were not overloaded. This year, he was fined 2,000 yuan and lost 6 points for illegal overloading, according to the Road Traffic Safety Law and traffic violation fines. Mr. Zhang from Hunan said that one refusal to an overloaded order will lead to a deduction of 5 behaviour points on the platform, but a driver has to complete 10 more orders to just increase 1 behaviour point, so if the points are deducted for refusing to take the overloaded cargo, the overall mark may not be able to go up for a month.

The reporter verified the case by placing an overloaded order on the platform, and found that despite there are rules that seem to limit overloading, the actual operation can be done at will. Truck overloading remains a safety concern, impacting drivers’ lives and road safety. Cargo owners’ desire for cost savings often transfers the risk and punishment of overloading to cargo drivers, leaving them with difficult choices.

CLB Insights

Challenges and concerns surrounding China's retirement age reform

As China grapples with a continuous decline in the working-age population and the prospect of state pension fund depletion, the Chinese government has proposed to raise the retirement age (voluntarily for now). However, the proposal aroused concerns among workers, especially blue-collar migrant workers.

It is difficult for migrant workers to find jobs that pay for social security for 15 years--the prerequisite for getting a pension when retired. Workers are worried that the retirement age reform would make things even harder.

There is a disparity in social security coverage and benefits between urban workers and migrant workers. Many migrant workers still have to work after the retirement age, with little or no social security. Precarious and informal employment across sectors is a significant reason and will likely continue with the growing gig economy.

For the full analysis, please see this article–which was collaborated by China Labour Bulletin and the SOAS student placement programme.

CLB in the news

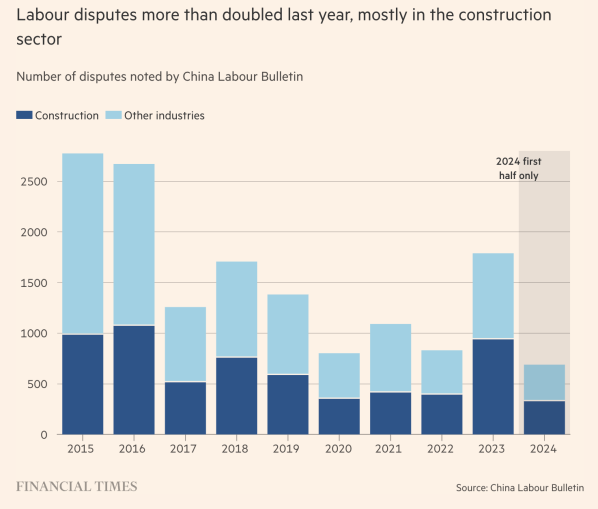

China Labour Bulletin was cited in an article published by Financial Times on the social strains that workers faced after the pandemic. It mentioned that the CLB Strike Map recorded “almost 1,800 incidents across China last year, more than double that of 2022 and exceeding pre-pandemic levels. The construction industry accounted for most incidents, followed by manufacturing”.

The declining real estate industry, the closures and relocations in export-oriented sectors such as electronics manufacturing, and the slowdown of internet companies’ development, have led to protests related to unpaid wages, layoffs and wage reductions. More workers felt mental stress and grew pessimistic about their situation, especially young college graduates, who suffered from intense competition at school.