- This CLB feature, told through the eyes of one garment factory worker who became a worker representative in negotiations upon factory shutdown, paints a picture of how the pandemic and slow economic recovery in China leads to tragedy when all peaceful means have been exhausted and those with authority offer no reasonable alternatives.

- When workers protested against the Huizhou factory shutdown in July 2023, they expressed not only dissatisfaction with the terms of the severance, but also that their eyes were opened to how the economic conditions of the past several years are disproportionately borne by them.

- Workers used all available channels to voice their concerns, and they and the factory involved local administrative and judicial departments as well as the official trade union. But this was to no avail: the factory’s initial low-ball severance offer was never deviated from in workers’ favour.

Starting in May 2023, workers at an export-oriented wool knitwear factory in Huizhou, Guangdong province, protested after several years of temporary shutdowns and low pay. The factory announced its permanent closure as of July 2023, and workers organised to try to win a more favourable severance package.

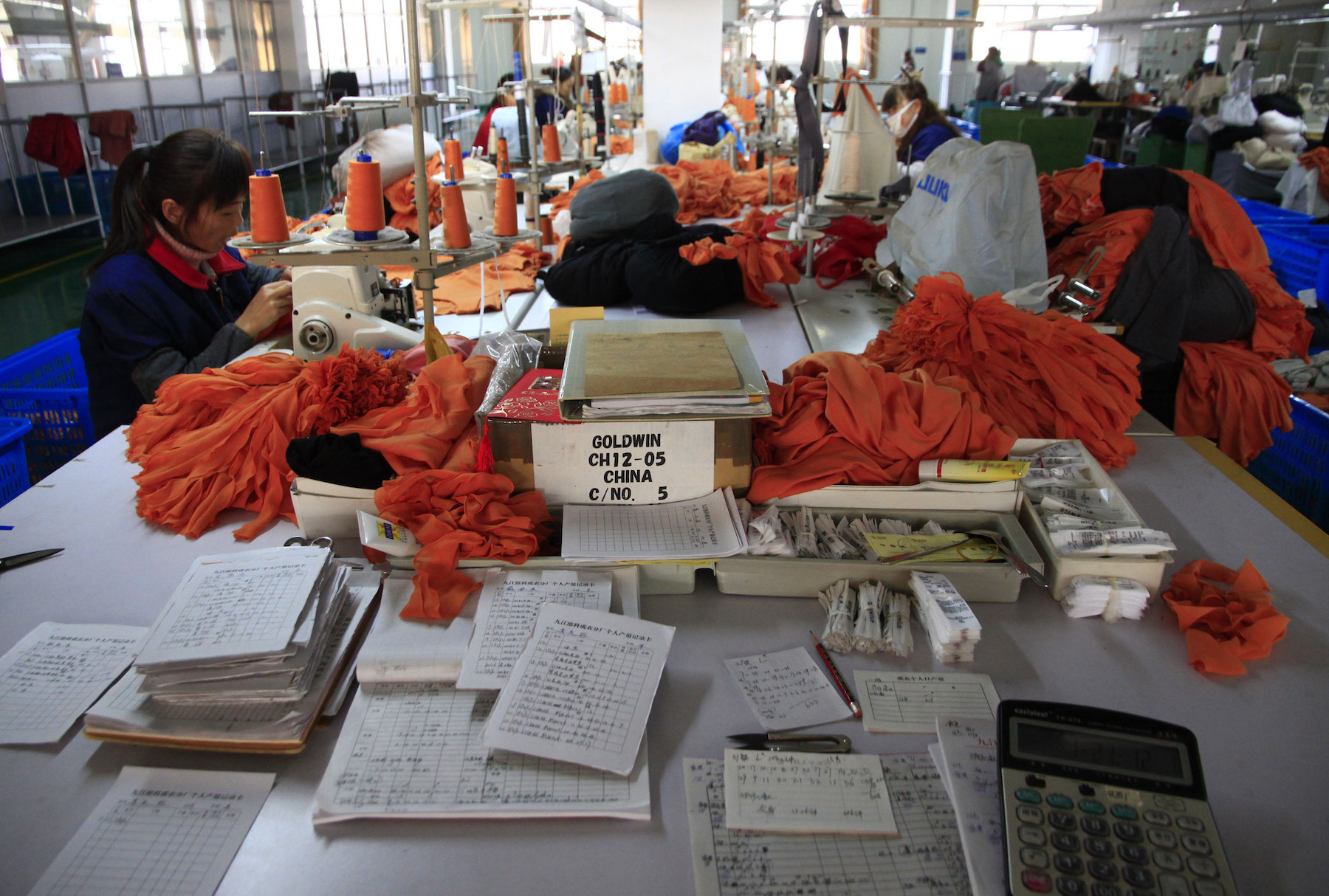

The Huidong County Kong Wai Knitting Co. Ltd (惠东县港惠针织有限公司, sometimes Romanised as Kwong Wai) is an indirect subsidiary of Fang Brothers Knitting Ltd. in Hong Kong, which supplies for brands in the Americas and Europe, including Ralph Lauren, Burberry, Brooks Brothers, J. Crew, Lululemon, Cabi, Calvin Klein, and Winser London.

The Kong Wai factory has been operating in Huizhou, Guangdong province, for over 30 years. Kong Wai was registered in 2011 as limited company, but it started production earlier as a "three supplies and one compensation" (三来一补) enterprise. This refers to a 1978 State Council plan to attract Hong Kong and Macau investments to Guangdong upon China’s Reform and Opening and into the 1990s.

Photograph: humphery / Shutterstock.com

At its peak, Kong Wai employed over 2,000 workers, but after the 2008 layoffs during the global recession, employment continued to drop from about 900 workers in 2016 down to less than 500 in 2021, according to annual reports on the number of workers registered for social insurance benefits. Worker chat records posted online indicate that only about 230 workers were employed as of this year.

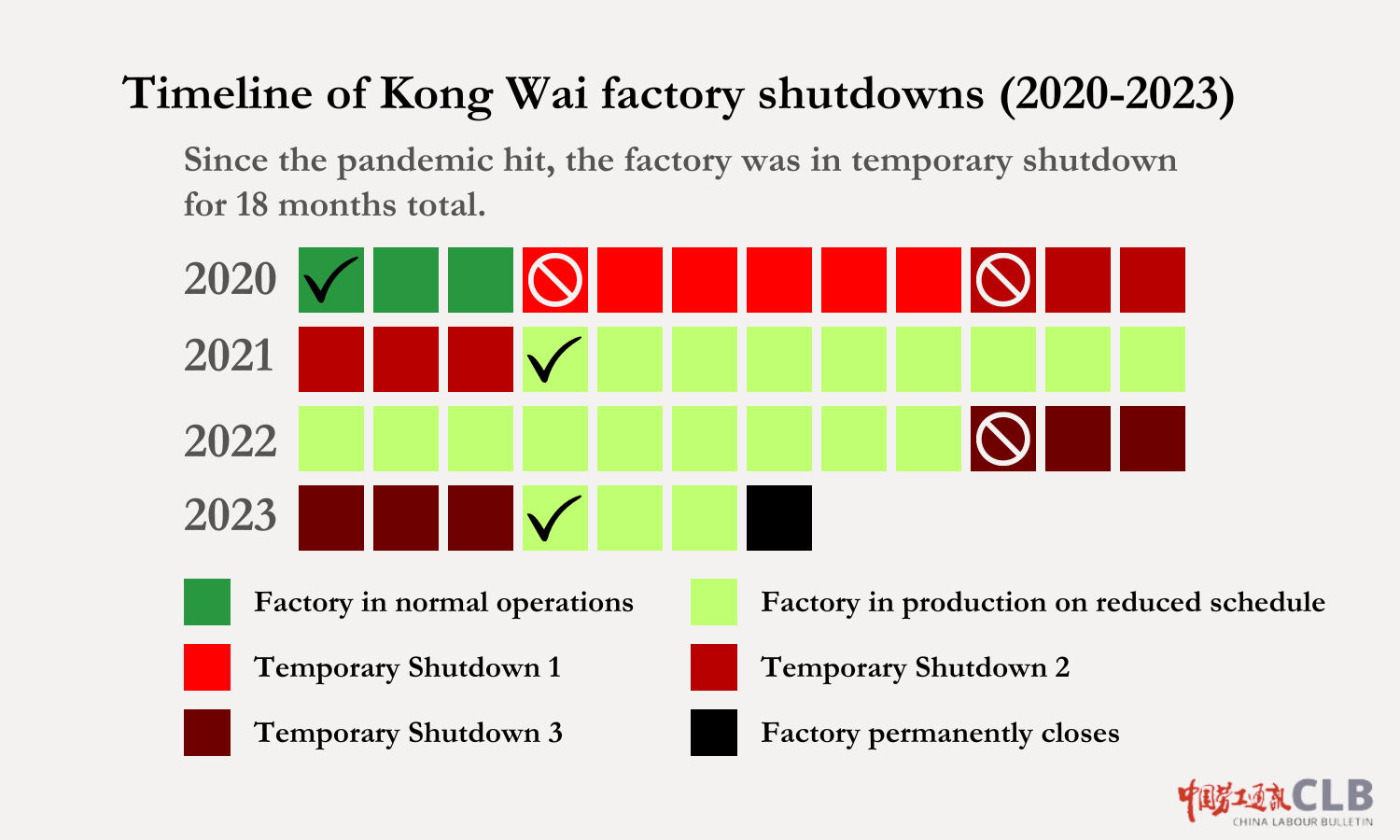

Those remaining workers had stuck it out through pandemic work stoppages, pay cuts, and extended periods of declining orders since 2020. The factory temporarily shut down several times between 2020 and 2023, finally resuming production in April 2023. The various shutdowns were explained by the factory in their official notices as being due to low order volumes from the U.S. and Europe under pandemic conditions, the inability of overseas visitors to enter China in early 2020, U.S-China tensions, the Ukraine War, and cargo difficulties in Hong Kong.

But upon resumption of production, workers began to believe that the situation would never get better, and that their co-workers who chose to resign over the past couple years to find more profitable work were unwittingly part of a suspected plan to slowly push workers out, reducing the amount of compensation to be paid upon eventual factory shutdown.

Those who remained employed despite lack of work wanted to receive their entitled severance and seniority pay. But in the end, they found that they were only legally owed a fraction of what they had expected, and the factory’s offer was even lower than that.

They protested, filed administrative complaints, and sought attention from the Hong Kong parent company. After exhausting various channels, they were invited to a multi-party negotiation that included local administrative and judicial departments and the official trade union. But in the end, the factory’s original winding-up plan was not deviated from.

Most of workers’ pay came from overtime and performance awards, which were cut in 2020

Worker Zhang is 38 years old and was among one of the remaining workers when the factory shut down in June 2023. She was elected as a worker representative to negotiate with the company. As a result of her numerous online posts, the story of the factory’s fall from its heyday and the effect on long-term workers like Zhang comes into focus.

Zhang joined the factory in 2001, when she was just a teenager. However, her seniority is only counted from 2008, the year China’s Labour Contract Law came into effect. That year, many employers signed new contracts with workers just before the law’s effective date, as a way to avoid some of the costs of compliance with the new law.

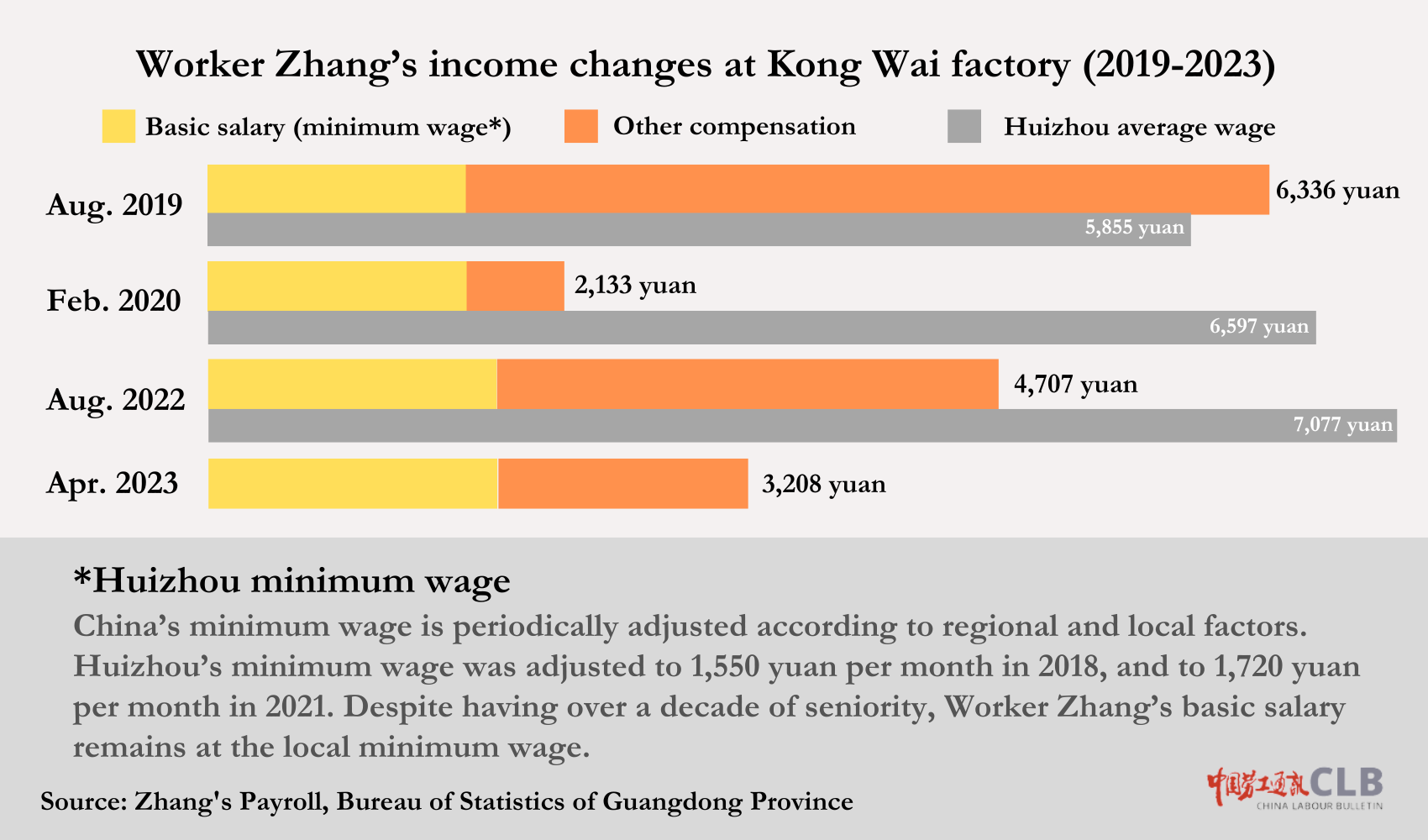

Zhang shared several of her pay records online. As of August 2019, Zhang was earning 6,336 yuan (U.S. $880) per month as a worker who prepares materials for production. With an official record of 11 years’ seniority, her basic salary was just 1,550 yuan per month, which is the exact minimum wage in Huizhou since 2018. The majority of her pay came from the combination of overtime (580 yuan), skill subsidies (640 yuan) and performance and award compensation (3,180 yuan).

By April 2023, her earnings had dropped to 3,208 yuan, just half of what she had been making in 2019. Of that 3,208 yuan, the largest portion was from the basic wage, which had increased to 1,720 yuan according to the local adjustment of the minimum wage.

For less senior workers, they could justify cutting their losses and seeking other work once trouble hit in 2020. But most of the 200 workers who rode out the storm were banking on the fact that they would be paid out upon factory closure according to the Labour Contract Law.

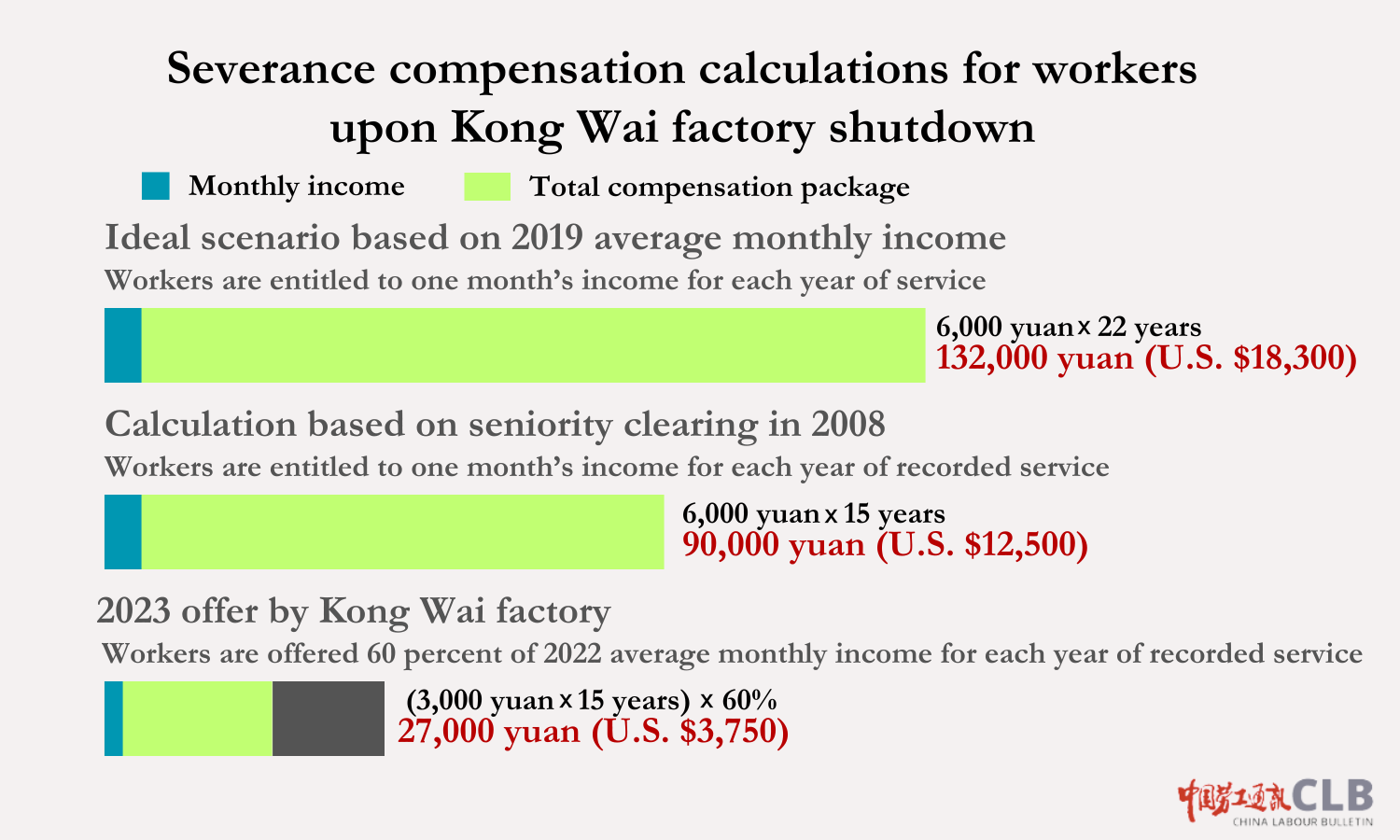

For a worker like Zhang with over a decade of seniority and an average monthly wage higher than the regional average wage as of 2019, the economic pay-out upon factory closure could be expected to be well over 100,000 yuan. But based on the previous year’s average wage levels as announced in the factory’s June 2023 notice, the pay-out was likely calculated as less than 30,000 yuan. This difference is significant for ordinary workers like Zhang and her colleagues.

Zhang said on 26 May 2023:

Right now, there is an undercurrent brewing among the workers in the factory, and we are becoming unified. A good show is about to be staged!

But despite Zhang’s leadership and the workers’ determination, and even though their demands are backed by law, workers need more leverage on their side when factories shut down for good.

Workers organized to fight April 2023 wage cuts, but management would not budge

After the October 2022 - April 2023 temporary shutdown, workers returned to the factory and worked at a less intense pace than before, because of a limited number of orders. They worked for only eight hours per day, five days per week. As Zhang’s April 2023 compensation shows, this reduced schedule makes it difficult for workers to earn more than the minimum wage.

On 30 May, the factory declared that workers’ wages for April - which had not been paid on time - would be calculated differently. The reason given was that the past two months’ productivity levels were similar to working only three days during normal periods. This blaming of workers for the low level of orders was not only offensive to workers, but also led to a reduction in their performance awards.

Workers received their April 2023 pay on 31 May and were dissatisfied with the low amount. First, they spoke out in a WeChat group, with Zhang asking for collective action to oppose the low salary, and workers one-by-one agreeing to join:

Colleagues who oppose the factory’s shorting us our pay, speak up about your ideas here. Silence will not resolve our problem.

One by one, colleagues chimed in:

I won’t accept the company shorting our wages!

I won’t accept it!

I won’t accept it!

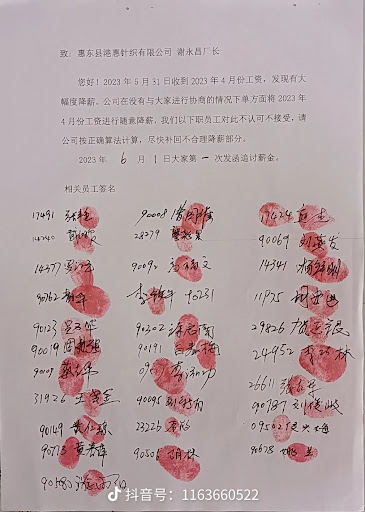

Workers also collected signatures on a complaint letter to factory management, which they delivered to the factory owner on 1 June. A total of 105 workers signed the letter, placing their thumbprints and work numbers on the document. Workers took their grievances to local administrative departments, and, in another appeal, they included the Fang Brothers company in Hong Kong, which indicated that the company lawyer would respond to workers.

A page of the workers’ 1 June 2023 complaint letter to the Kong Wai factory, showing dozens of workers’ signatures. Source: CLB Strike Map

On 9 June, management escalated the conflict by calling in the local police, further deteriorating the labour relations.

Then on 26 June, the factory issued an explanation letter acknowledging that workers lost at least 50 percent of their performance pay. However, the factory emphasised that its actions do not violate labour laws, because the contract only requires that workers’ wages cannot be lower than the local minimum wage. Instead, the performance wage is floating and can be decided by management.

Hence, the company said, the workers’ allegation of a wage cut has “no legal or factual basis.” The factory letter encouraged workers to use legal channels if they have disputes.

Before the April 2023 wage matter was settled, the factory declared official closure on 30 June, effective 1 July. Workers were required to vacate the factory dorms by 15 July.

The announcement stated reasons of economic difficulty and lack of workers’ cooperation. In its notice, the factory specified that workers have the choice to accept the company’s offer to receive 60 percent of a calculation based on the past year’s average wages and each worker’s seniority. Signing this offer means workers agree to waive other legal rights. For those who do not sign, they can only resort to judicial proceedings, like labour dispute arbitration.

Workers gather outside the Kong Wai factory and confront a manager. Source: CLB Strike Map

In a video dated 4 July, a manager is seen speaking to a crowd of angry workers, saying that the company has only 300,000 yuan cash and that workers will get only 30 percent of the offered calculation. The workers can be heard asking the manager about the accountability of the Hong Kong parent company, but the manager pits the corporations against each other, saying the Hong Kong company would treat the workers more harshly. And if they don’t take the offer and instead wait for bankruptcy, their fate may be even worse, he said.

On 5 July, the Kong Wai factory invited officers from the local labour bureau, labour inspectorate, official trade union, and justice bureau to join in negotiations at the factory. Workers elected seven representatives to negotiate the following morning. Zhang took part in the negotiations on 6 July and expressed online her disappointment that the factory did not budge an inch:

A dead pig is not afraid of boiling water! What can we workers do after resorting to all available channels? We want to cry, but we have cried all our tears by now. With such bad company, where can we find justice?

CLB has been unable to confirm the final offer to workers. Zhang posted again in August to indicate that about 30 of the workers did not accept the factory’s offer and will pursue legal channels on their own.

Kong Wai workers prepare to negotiate. Source: CLB Strike Map

In fact, Zhang is no stranger to trying to hold the Kong Wai factory accountable under China’s legal mechanisms for workers’ rights. In 2020, she took a case to labour dispute arbitration, after which the factory retaliated by changing her job duties in March of that year. In August 2022, she made an official complaint to the local taxation bureau for unpaid social insurance benefits dating back to 2012. The department found in her favour, but the factory never cooperated and the bureau transferred her case to a different department. CLB is unaware of any result.

For the 30 workers at Kong Wai holding out for legal redress, the manager who spoke to workers may be right: the factory may in all likelihood be out of funds so that even if workers prevail in labour dispute arbitration or the civil courts, they may never receive compensation.

Is there a better way forward for China’s manufacturing industry?

China’s manufacturing sector has been contracting for almost a decade now, with more acute effects since 2020, and a wave of relocations and shutdowns since early 2023. Companies are making difficult business decisions directly affecting workers. However, there are stakeholders beyond the local governments, the factories, and the workers themselves.

Regional suppliers and international brands are changing their purchasing patterns. In this case in Huizhou, the Hong Kong parent company has a factory in Jiangsu province and one in Vietnam. Brands like Ralph Lauren, Burberry and Calvin Klein selling products internationally can also be involved in conversations about how suppliers, factories, and workers are affected.

In this case and others like it, China’s domestic laws are not enough to ensure workers’ rights are protected. But new supply chain due diligence legislation like that being enacted in the European Union, France, and Germany, have the potential to be useful for China’s workers and local economies alike during this period of struggling for survival.

China’s official trade union can have a role to play in involving more stakeholders in conversations about workers’ rights. In this case at Kong Wai, the Huidong county federation of trade unions was aware of the Kong Wai factory’s deteriorating situation and the resulting effect on workers. The union was involved in shutdown negotiations, and workers had lodged administrative complaints prior to that.

However, the county-level union was quite busy with routine propaganda activities during relevant periods, setting up a service station for delivery workers, throwing a fair on International Labour Day, and sending bottled water to outdoor workers. Most remarkably, in June 2023 - during the same week that the Kong Wai factory called the police to intervene in the workers’ protest - Huidong union officials were attending a week-long leadership training in Shandong province, which included a session on “How to handle emergent incidents and manage public opinion in a complete media era.”

Although not all of the union’s recent activities are completely meaningless, union officials can do much more when workers on their doorsteps are facing ongoing labour rights disputes. The role of a real union is to represent workers, and China’s official union has the leverage to involve local government actors, regional suppliers, and international brands in finding a common solution that upholds workers’ rights.

Further CLB reading:

- Surge of manufacturing protests in China deserves international attention (May 2023)

- What You Need to Know About Workers in China: Workers’ rights and labour relations in China (updated July 2023)

- Global South workers have a new solution in light of brands’ unpaid Rana Plaza debt (April 2023)