At least 62 miners have been killed in two major coal mine accidents in China in the last month, according to official media reports. The final death toll is likely to be higher still once rescue efforts have finally been called off.

Forty five miners have already been confirmed dead, with two still missing and dozens more badly injured, many with carbon monoxide poisoning, after a gas explosion in the Xiaojiawan coal mine near Panzhihua in Sichuan on 29 August. A total of 154 miners were reportedly underground at the time of the blast. So far, 107 have been rescued. High temperatures, dense pockets of gas and rock falls have hampered rescue efforts.

In the north-eastern province of Jilin, 17 miners have been confirmed dead, although the actual total will almost certainly be 20, after a massive gas and coal dust explosion ripped through the Jisheng coal mine near the city of Baishan in the early hours of 13 August. High levels of gas made rescue efforts very difficult, officials said, giving little hope for the three miners still listed as missing.

Together with a spate of fatal traffic accidents, explosions and bridge collapses in China, the mine disasters have once again led to soul searching in the official media, with the Xinhua news agency dubbing August a “bloody” month.

And the death toll in China’s mines could have been even higher had not another 28 miners been rescued after two separate mine shaft collapses in the northern provinces of Shaanxi and Shanxi. On 16 August, 16 miners were trapped when a roof in the Ruifeng coal mine in Shaanxi collapsed. Fifteen miners were rescued. And on 29 August, seven miners who had been trapped by roof collapse for two days in another mine in the coal heartland of Shanxi, walked out of the mine with their rescue team to join their six colleagues who had escaped at the time of the collapse.

Up until August, China’s coal mine safety record seemed to be showing signs of improvement with only eight major accidents logged on the State Administration of Work Safety (SAWS) website in the first seven months of 2012, compared with 19 for the whole of 2011.

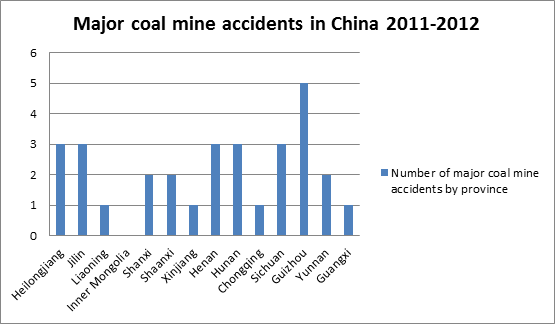

Looking at the SAWS figures, a very clear geographical pattern is emerging in which major accidents are now far more common outside the traditional coal producing provinces of Shanxi and Inner Mongolia than within them. Indeed, only two of the 30 major accidents recorded by SAWS since the beginning of 2011 occurred in the coal heartland. Compare this to the period between 2003 and 2008 when China’s coal mine safety record was at its worst. At that time, 45 of the 192 major coalmine disasters officially recorded occurred in Shanxi alone.

But while Shanxi has clearly improved its safety record by closing down small and unlicensed mines and bringing production back under more centralised provincial control, other provinces, particularly in the southwest of China continue to be very lax in the enforcement of safety standards. As the graph below shows, exactly half of the major accidents recorded since early 2011 occurred in the south-western provinces of Hunan, Chongqing, Sichuan, Guizhou, Yunnan and Guangxi.

If China is to improve its overall coal mine safety record, these problem provinces in the southwest will, like Shanxi, have to take a series of tough measures and ensure that safety really does come before profit in the operation of coal mines. The prescription adopted by Shanxi might not necessarily work in these less concentrated coal mining areas but a good starting point would be to raise miners’ wages, give them better training and crucially a greater say in the day to day management of mine safety.