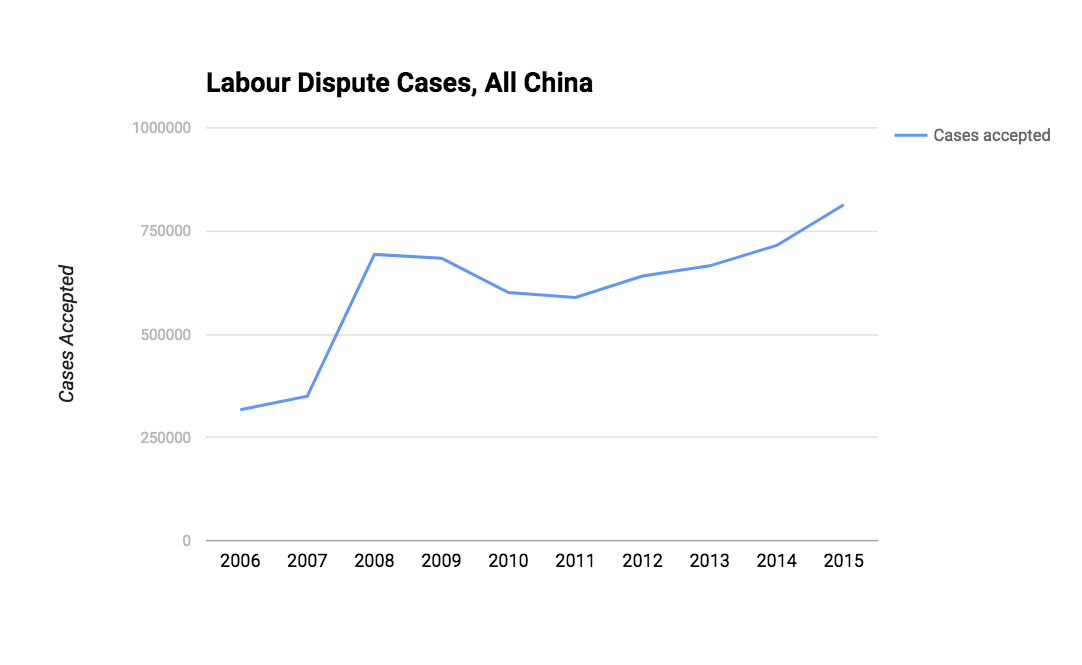

According to the latest national statistics, labour disputes have far surpassed record highs reached during the financial crisis of 2008, and continue to climb.

Statistics from the latest China Labour Statistical Yearbook show that labour dispute arbitration committee (LDAC) cases in China have been steadily climbing since 2011 and have far exceeded the last climax of dispute cases reached after the global financial crisis of 2008. The number of workers involved in labour disputes also surpassed 1 million, nearly equal to the all time high reached in 2008.

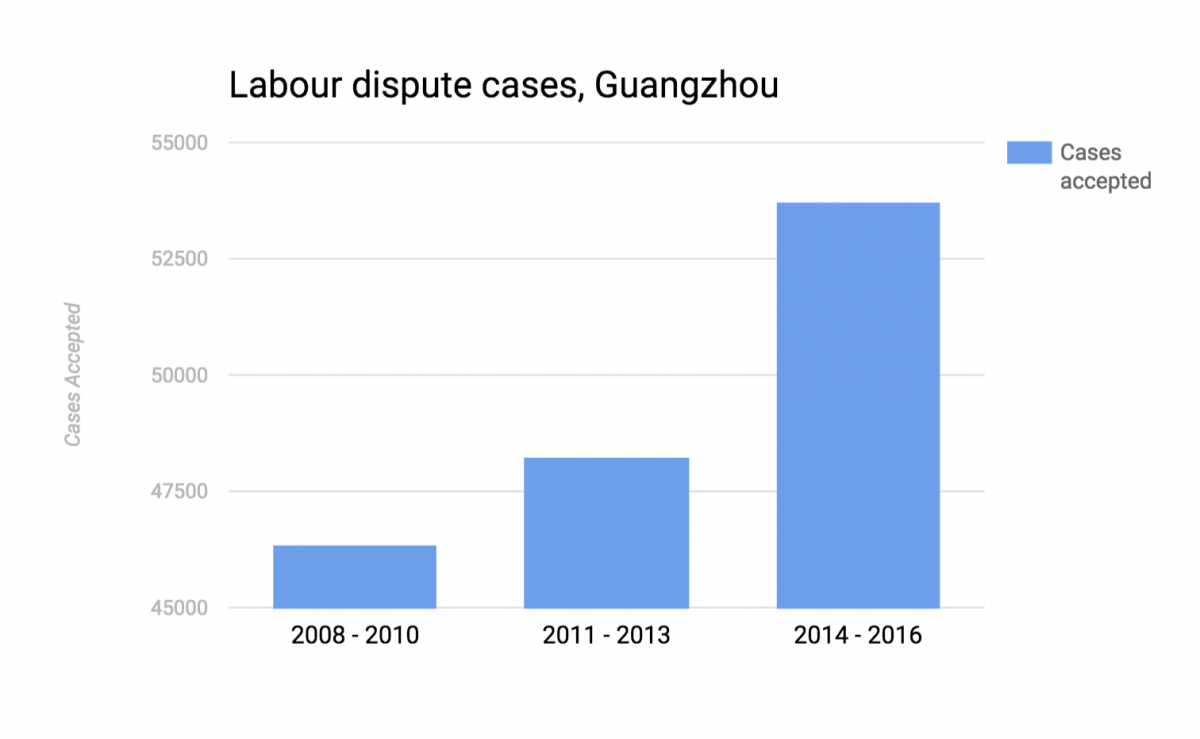

While latest national LDAC case data compiles data only up to 2015, local government reports reveal more recent statistics, and tell stories of the rising rights awareness of workers.

A whitepaper on labour disputes from Guangzhou noted the increasing diversity of grievances raised by workers in recent years. Unpaid social insurance, for example, account for over 40% of all arbitration cases over the past three years. Women workers are an increasing portion of all cases, and are taking action against unequal treatment, illegal firings or wage cuts during pregnancy or maternity leave, and discriminatory hiring practices.

A similar whitepaper from Qingdao reported that disputes are becoming more complex and potentially harder to solve as workers are including more than one grievance per case. In addition, the Qingdao report highlighted increasing informalisation of work, with more cases involving the lack of a labour contract or unequal pay, a typical situation among agency workers.

Official reports have primarily blamed economic factors for spikes in labour disputes, the economic crisis of 2008 and the latest rise on the “new normal” and the economic slowdown in general. Some calls for change to the labour dispute resolution system raise the need for institutional change, but focus on managing problems after they erupt rather than resolving conflicts before they develop.

Other indicators like worker strikes and protests, which are not released by official records, show that tensions are rising, and workers increasingly willing to take action to defend their rights. CLB’s strike map recorded over 8000 worker collective actions in the five-year period between 2011 and 2016.

While solutions are clearly in urgent need, the repression of labour NGOs and worker activists has increased, and proved counterproductive in reducing labour tensions.

In order to truly address labour tensions, the government needs to embrace the same solutions promoted by many NGOs and activists: regular collective bargaining in conjunction with an authentic and representative trade union. With these reforms in place, not only would the number of disputes likely fall but the vast majority of labour rights violations could be prevented from occurring when workers have the power to defend their rights in their own workplaces.